A Modern Review of Thidrekssaga

Merovingians by the Svava

|

| |

|

by Rolf Badenhausen

|

|

Date:

2023-03-18

| Update

History | |

|

|

|

|

Contents

Introduction

1. The original narrative geography: The Old Norse & Swedish texts

2. King Theuderic I = King Thidrek of Bern

3. Some literary and historical environments

3.1 'Gransport'

3.2 Some historical and literary analogues

3.3 Theuderic's provenance and disappearance after 507

3.4 'Fluchtsage'

3.5 Some interliterary receptions

4. Low Saxon Historiography and the 'Annals'

4.1 The Quedlinburg Annals' (QA) 'Second Source'

4.2 Historiographical validations: Frankish and Saxon history

4.3 Guðrún's sons vs Ermanric by the 'Second Source'

4.4 Second 'Attila' and Second 'Odoacer' by the 'Second Source'

5. How reliable is Gregory of Tours east of the Rhine ?

6. Interliterary recognitions: Chlodio and Hloðr in northern

Húnaland

7. Theuderic I or Thidrek of Bern:

«King of Bonn»

8. Which are the dynasties of the eastern Franks of 5th century ?

9. King Sigibert of Cologne = King Sigurð the Nibelung ?

9.1 Sigibert & Sigurð: How far can we follow Gregory and the

saga?

10. Preliminary Filiations

10.1 Ermenrik and Samson

10.2 Weland and Widga

10.3 Atala of Susat and a perspective survey

10.4 Some literary-historical perspectives

11. Early

activities in Baltic lands and Western Russia

11.1 Remarks on 'Historicity' of 'Vilkinaland' and other Baltic lands

11.2 Ostancia, queen of 'Vilkinaland',

Baltic Sea Region

12. Résumé

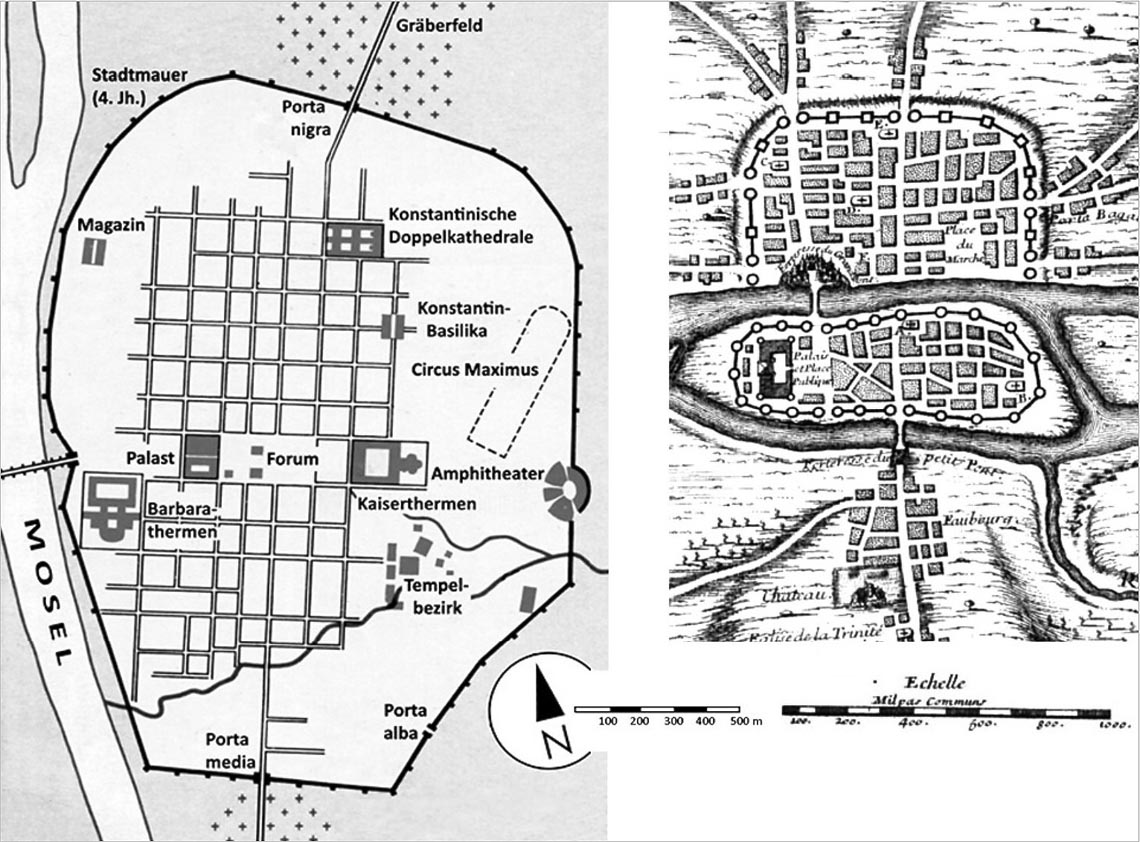

12.1 General conformity of contemporary residential

regions

Trier = Roma II on the Moselle and Cologne–Bonn–Verona–Zülpich

12.2 Common geostrategical ambitions

12.3 Dénouements

on literary milieu

Endnotes

Appendix

A1

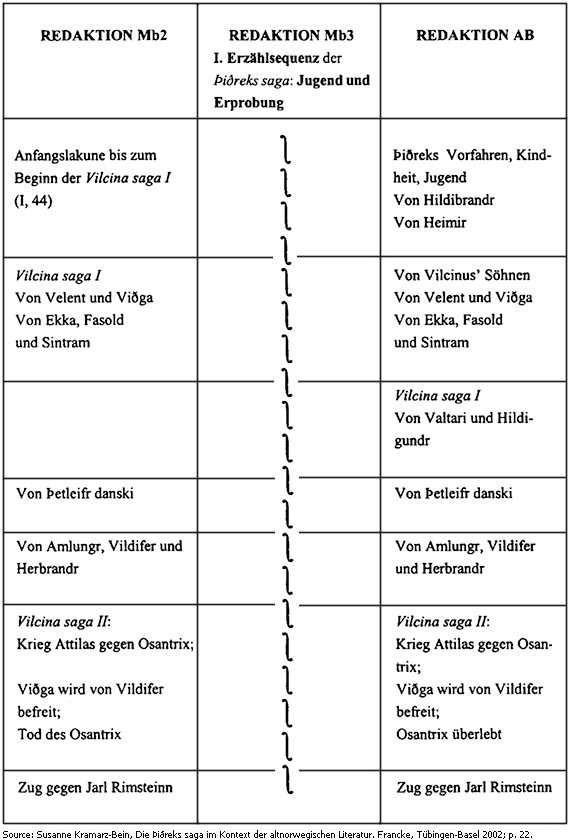

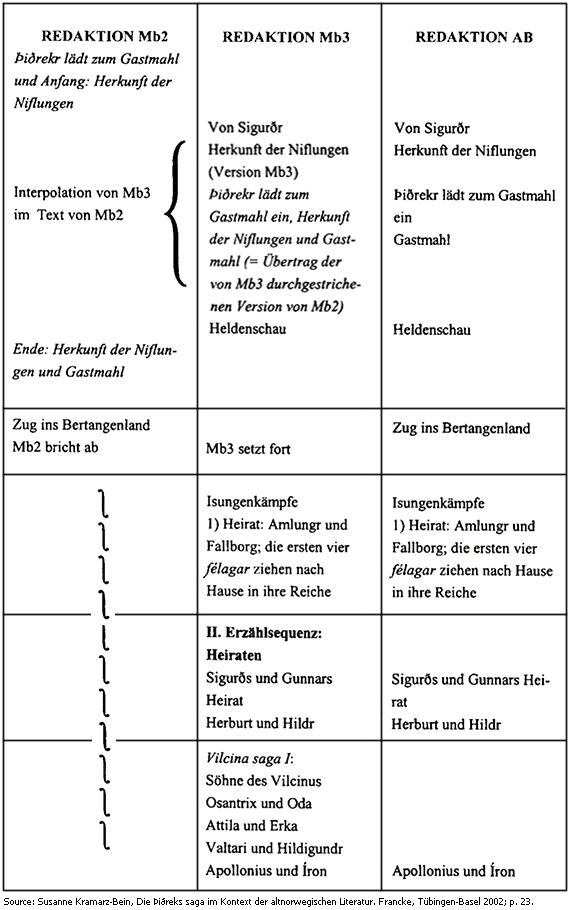

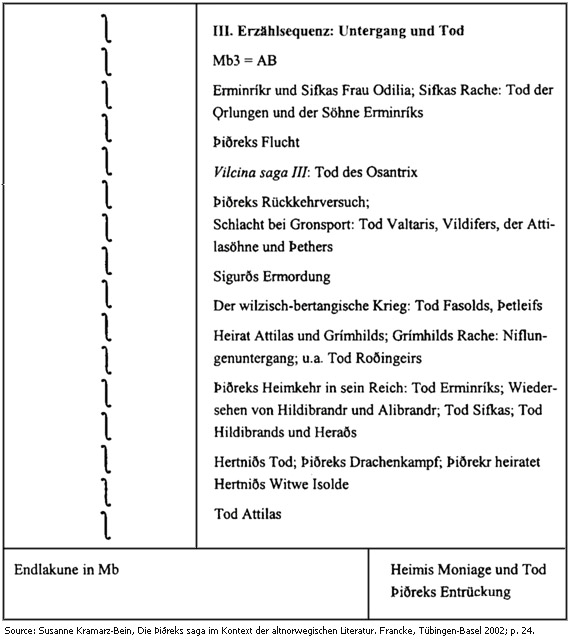

Remarks on the evaluation of Thidrekssaga manuscripts

A2

Edward R. Haymes on oral tradition and Thidrekssaga

A3

Supplementary articles by the author

A4

External publications

|

Introduction

The reviewing literary research

into Old Norse and Swedish traditions, as initiated by Heinz

Ritter-Schaumburg, PhD († 1994), might motivate

not only experts in Late Antiquity and prae-mediaeval times

to take note of some new interesting context: The Old Norse

Thidrekssaga and Old Swedish ‘Didriks chronicle’, both

appearing closely related to the sagas or legends about an

«Ostrogothic Dietrich von Bern», seem to throw back certain

narrative light from Frankish

history, whose Merovingian origin and its 5 th–6 th-century

period have been retold by Gregory of Tours,

Fredegar’s Chronicle and the Liber Historiae Francorum, a

further important chronicle of Frankish history.

|

|

Contradicting scholastic

conviction, Ritter has evaluated the mediaeval Old Swedish texts he

shortly called Svava, catalogued as E 9013, of

Skokloster-Codex, formerly No. I/115 & 116

quarto, at the ‘Riksarkivet’ Stockholm, as

more objective copy from an early but unknown archaic manuscript

being prior to the more longwinded narrating Thidrekssaga

which, however, is of surviving elder version and sometimes

rendering more topographical information.(1)

As the late philologist was able to prove by means of his numerous

German

publications and lectures, these manuscripts cannot mean the

‘Ostrogothic Theoderic’ mainly for both topographical and biographical

reasons,

but rather provide narration related to an equally named Frankish

king, the Old Swedish Didrik, who started his rise at ‘Bern(e)’

in the northern Rhine-Eifel outland.(2) |

| |

|

|

Heinz

Ritter’s translation of the Didriks-Chronik or ‘Svava’ (Publisher: Otto

Reichl, St. Goar 1989) is based on Sagan

om Didrik af Bern efter svenska handskrifter by Gunnar

Olof

Hyltén-Cavallius, Stockholm 1850–1854.

Regarding the literary style of the Old Swedish manuscripts,

Hyltén-Cavallius

classified at first the Old Swedish manuscripts as prosaic

‘krönikan’. Henrik Bertelsen

and Bengt Henning also shared this evaluation

(Bertelsen, ‘Didrikskroniken’ 1905–1911; Henning,

‘Didrikskrönikan’

1970). Edward R. Haymes translated the supplemental chapters of

the Old Swedish scribes under the headline The

End of Vidga and King Thidrek according to the Swedish Chronicle of

Thidrek.

The first complete translation of Hyltén-Cavallius'

svenska

handskrifter into English

language has been provided by Ian

Cumpstey: The

Saga of Didrik of Bern.

Although he follows a few questionable and inappropriate geonymic

equations by

elder scholarship (cf. for

instance ‘Spain’ with Ispania/Yspania, ‘Greece’

with Greken in his Index

of Place Names, he neither

situates Didrik’s seat in an Ostrogothic milieu nor connects the

leaders of Nyfflingaland with a

Burgundian environment in his appended

indexes. He briefly constates, p. vi,

that it

seems that the Swedish writers based their version of the saga on a

translation from the Norwegian (Old Norse). But rather than merely

translating, they produced an edition that was somewhat shorter,

with some repeated passages omitted, and with some parts of the

text reordered to give a more coherent reading order. It also seems

that they may have added from other unknown sources.

|

|

|

Regarding a circumspect

re-evaluation of the aforementioned manuscripts and other records of

occidental antiquity, we obviously have to contemplate a sharp natural

limit

that was previously forming the big border between the Roman Empire

and Germanic tribes, and, later again, the Franks and more eastern

folks: The Rhine. Apparently, our first

Frankish historiographers or ‘chroniclers’ would hardly cross that

river to have

a look at the outlandish tribes beyond;

and almost all their foreign colleagues seem to have left an almost

blank sheet about their history, particularly from the times

after the downfall of the Roman Empire to Charlemagne.

|

|

1.

The

original narrative geography: The Old Norse and Swedish texts

Heinz Ritter’s primal

geographical terminology of Thidrekssaga and Old Swedish

‘Didriks

chronicle’ represents an interesting result of his diligent

verification of intertextual location and hydronymic names.

With respect to the environment and localization of Bern, the 1 st-century

Roman Eifel Map, issued by Kurt

Stade, provides a

Roman based mining location nowadays called Breinig (‘ Breinigerbg.’)

at the exceptional Gallic-Roman temple site VARNE (VARN

→ VERN → BERN).(3)

Although the contemporary name of Breinig was not

handed down, the name of this place has been suggested as a derivation

based on Varneniacum

→ Bereniacum → Breniacum (Otto

Klaus Schmich, Hünen,

Viöl 1999, p. 306), as we have to come back later to the

region

of these

and other related places on account of both geohistorical and the

narrative

geostrategical contexts.

|

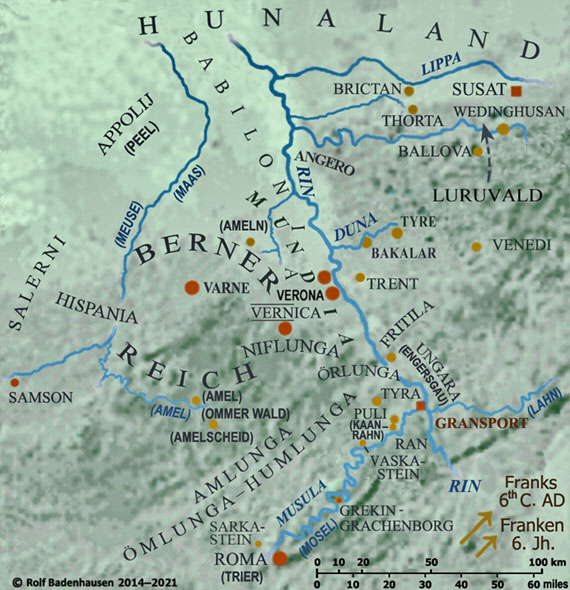

|

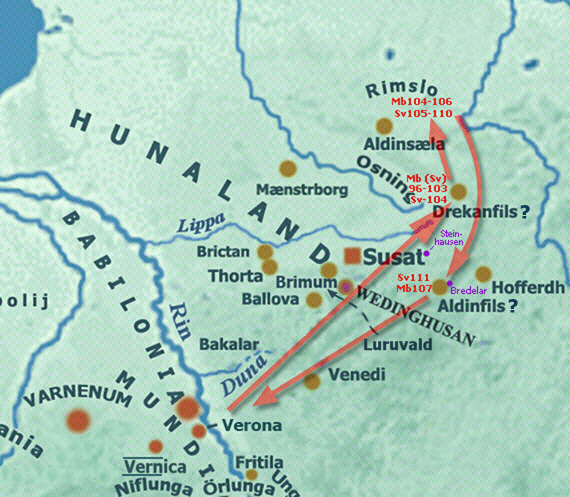

Some

important

locations of ‘Didriks chronicle’ and Thidrekssaga.

The place being named VARNENUM

has been excavated at Kornelimünster, suburban location of

Aachen (the Roman AQUAE GRANNI ), a place of

residence of Charlemagne.

With respect to Vereinnahmungsstrategien

für die Gestalt des Thidrek aus dem Milieu des

ostgotischen Theoderich – strategical

claims for setting up a

non-negligible ‘Ostrogothic Theoderic milieu’ for Thidrek –,

in particular created by elder German scholarship of 20th

century and vastly

colported by not a few philologists writing for the RGA

and Wikipedia, there is, for example, no passage

in the Old Norse + Swedish manuscripts

which connects their protagonists ‘Thidrek’

and ‘Ermenrik’ with the ‘gens Amalorum’, as these texts

do refer to this German Eifel folk ‘Amlunga’ in nothing more than

geographical

context. As regards Dietrich’s follower ‘Amlung’, son of ‘Hornboge’,

Ritter introduces the former clarifyingly in Dietrich

von

Bern, Munich 1982,

p. 296, en. 77.

Since the earlier and/or in Migration Period insufficiently recorded

ancestors of Sayn-Wittgenstein dynasty have been estimated between

Westfalia and the confluence of the Rhine and Moselle rivers,

Dietrich’s contemporary ‘Widga’

(this spelling form by the translators August Raszmann

and Fine Erichsen) must not necessarily come from

the other side of the Alps; see Mb 79 & 283.(4)

Generally, the Old Swedish forms ‘Wideke’, ‘Wideki’ might potentially

reflect the result of shortening derivation from Old German

‘Widechinstein’.

Ritter underlines well that the mediaeval scribes of the ‘Didriks

chronicle’

and Thidrekssaga may refer to geographical names ‘formerly

known as’ or, instead, ‘recently known as’. As concerns historical

records with limitations to less comprehensive context,

Ritter also subsumed that name giving to locations, their

etymological history and early historical events could have

taken place even before ‘first certified documentary

mention’.

|

|

|

Some geonyms

of the Old Norse + Swedish texts are not provided by other records of

Migration Period and Middle Ages, whereas

many other geographical expressions can be recognized in several

sources. For example Bardengau

(→ Berdengau)

→ (‘understood as’) Bertanga, the former

localized on the Lower

Elbe in connection with Charlemagne’s Saxon War campaigns, the latter

being used by the scribes of the

Old Norse and, with some spelling derivation, Old Swedish texts. (The paco

Badinc provided by the Annales

Petaviani has been annotated as «pagi

Bardengan caput Bardowik erat» by the MGH

editor G. H. Pertz, see William J. Pfaff 1959.(5)

The ‘Örlunga’

or ‘Harlungen’ region includes the former Roman BRISIACUM which is in

current German spelling (Bad) Breisig.

|

|

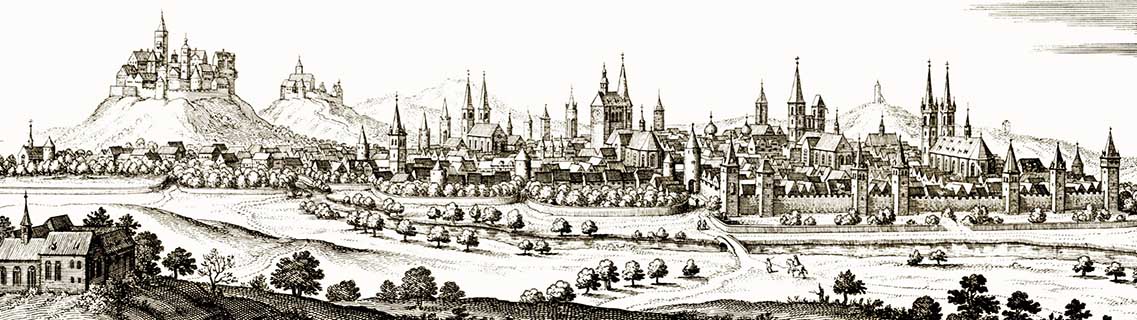

European Map

of

Thidrekssaga.

(3840 x 2880

pix.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Since Heinz Ritter has thoroughly

translated the Old Swedish ‘Didriks

chronicle’ into German language and reviewed the Thidrekssaga

manuscripts, the regions of today’s North Rhine-Westphalia,

the Rhineland and its Palatinate, Low

Saxony, Jutland and western Baltic territories appear as authentic

locations focused by ancient and mediaeval historiographers who

enticingly forwarded lifetime events related to a king of an obvious

Franco-Rhenish descent.

|

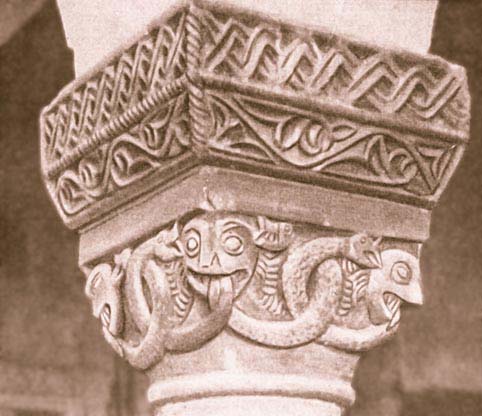

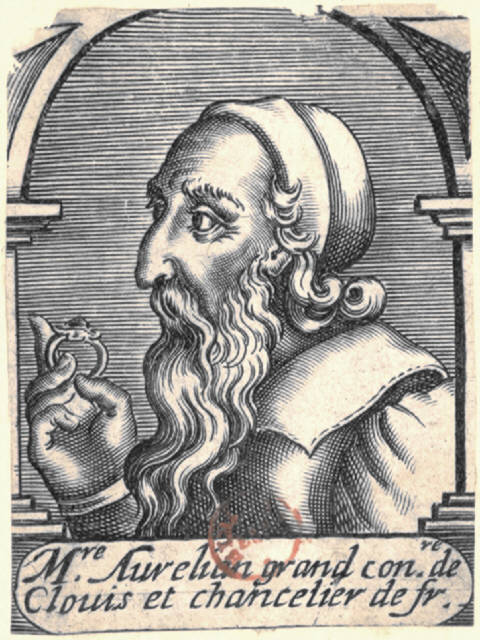

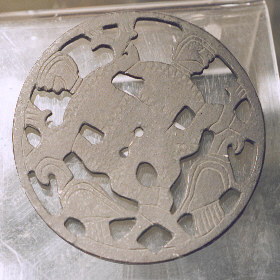

An

ancient seal of Trier on the Moselle, 11th

century.

Source: Ernst F. Jung, Der

Nibelungenzug

durchs Bergische Land (1987), p. 97.

|

|

|

Nonetheless, we must carefully

study their records to find some synchronous or completing

passages about Franco-Rhenish politics

of 5th

and the first third of 6th

century. Regarding the Rhine again as dominant natural and

cultural border, they seem to have had nearly the

same limited geographical horizon of recitation as

their Frankish colleagues vice versa. Thus, besides

primal geographical terminology, we have to interpret the Old

Norse + Swedish writers'

farthest known

southern centre ROME as ‘Roma

secunda’, whose spelling, localization and significance

is unmistakably provable as the Roman Augusta Treverorum

(today: Trier on the Moselle) through both historical and

geostrategical contexts. However, we should

not expect a detailed recitation of the Merovingian bloodline from

Thidrek’s ‘biographers’ who certainly were not crossing the

Meuse westward, therefore providing fragmentary views,

and we also should keep an eye on the right sequence of more

than 300 chapters written by the scribes of the ‘Didriks

chronicle’ and Thidrekssaga.

|

|

2.

King

Theuderic I = King Thidrek of Bern

|

|

|

|

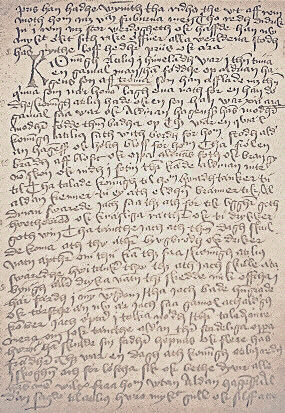

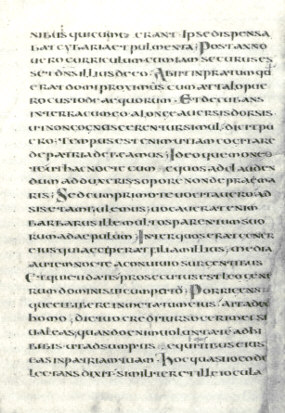

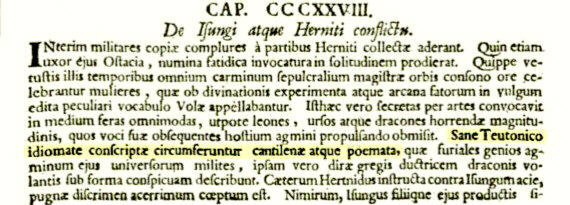

A colourized page of Thidrekssaga. (Perg. fol. nr.

4), cf.

H. Bertelsen, ÞIÐRIKS

SAGA, 1905-11, I, pgs 279–282.

|

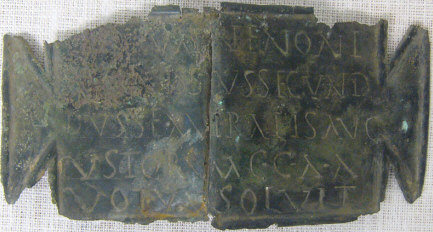

A photocopy from

Old Swedish manuscript,

ch. 365 of the mediaeval Skokloster folio.

|

|

|

|

Since the ‘Didriks chronicle’ and its derived

epic novel Thidreks saga,

as Ritter prefers this literary classification (see Der

Schmied Weland; posthumously published by Olms, Hildesheim 1999),

like to put forward

some coherent historical information and relations

upon large territories of today’s Central and North Europe, we

should estimate with him that these texts would basically not prefer

depiction of any less important provincial antics against more

reasonable reports on superior events. Evaluating Ritter’s conclusions

by means of the momentous context of the Old Norse +

Swedish

manuscripts on

such level, we finally will be confronted with the impasse

of not enough geographical, temporal and personal space for

Theuderic ‘&’ Thidrek.

|

|

It has been considered that

– Thidrek, Franco-Rhenish king, died c.

534–36

according to Ritter’s estimation;

– Theuderic, not only Franco-Rhenish king, died at the end

of

533.

|

|

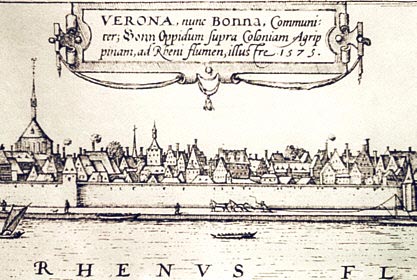

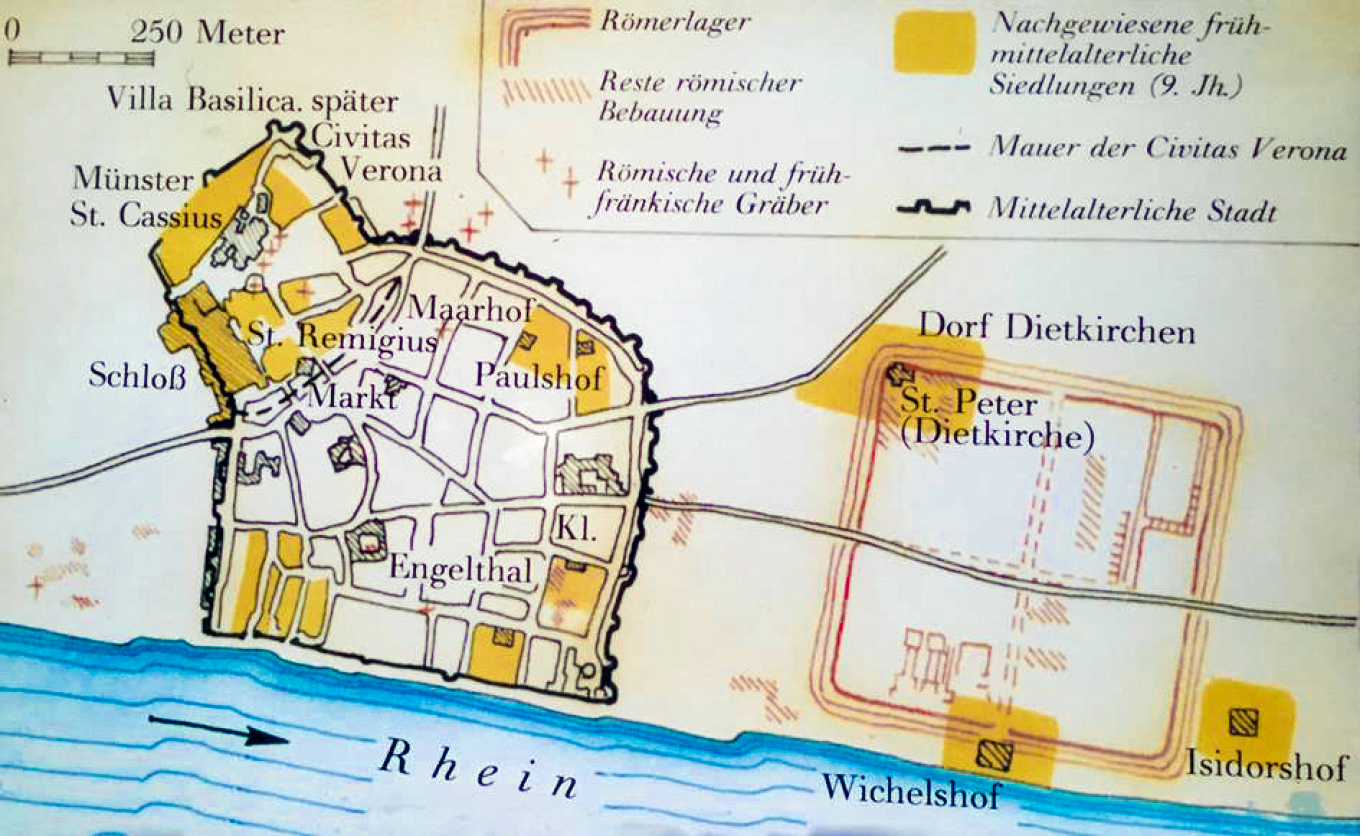

Kemp Malone (1959) and Karl Simrock,

German translator of the Nibelungenlied, Old Norse Epics and the Old

English Beowulf, identify Dietrich

von Bern with Frankish king Theuderic I.

Simrock,

reviewing and basically following his colleague Prof. Laurenz Lersch,

pleads for a primordial (Franco-)Rhenish tradition that centers

on Bonn = Verona (notably already Franz

Joseph

Mone) which, as these scholars do generally combine, thereafter

was assimilated and enriched by receiving authors of southern Dietrich

von Bern

epics. (F. J. Mone, Untersuchungen zur Geschichte

der

teutschen Heldensage, 1836, p. 67; id. Anzeiger für Kunde

der teutschen Vorzeit, 1836, p. 418.

Laurenz Lersch, Verona., in: Jahrbücher

des Vereins von Alterthumsfreunden im Rheinlande. Bonn 1842, I, pgs

1–34. Karl Simrock, Bonna Verona. In: Bonn. Beiträge

zu seiner Geschichte und seinen Denkmälern. Festschrift Bonn

1868, III, pgs 1–20.)

Karl Müllenhoff, another 19 th-century

scholar, tried to discern Dietrich von Bern as an amalgamation

of Frankish kings Theuderic and his son Theudebert with a poetical

‘Ostrogothic Theoderic’ (Die austrasische

Dietrichsage,

in: ZfdA 6 (1848), pgs 435–459). Thereafter

Hermann Lorenz declared Frankish king

Theuderic I as the prototype serving for the Dietrich

epics, estimating [transl.] «Theuderic utterly drawn into

the

circle of the Gothic Dietrich saga, in it only faint echoes that denote

him here as the historical Frankish king.» (Das

Zeugniss für die

deutsche Heldensage in den Annalen von Quedlinburg, in: GERMANIA

31 [19, 1886], pgs 137–150, p. 139.)

Regarding newer publications, Helmut G. Vitt renders short but astute

initial intercessions resulting in Thidrek =

Theuderic I and Samson = Childeric I: Wieland der Schmied

(ISBN 3 925498 00 1), pgs 127–138.

However, all these authors do not provide detailed studies which ought

to

substantiate more firmly their opinion.(6) |

|

We must state deficient biographical

information about that young Theuderic before 507 and, again, before c.

525. He is mentioned as most talented son of C(h)lodovocar

I

or ‘Clovis’ in the texts written by Bishop Gregory of Tours, principal

Frankish ‘chronicler’ whom we obviously have to credit

with

truth telling and who might appear to some item more informative than

the pseudonymous Fredegar.

Unfortunately, Gregory has not left a

line to find the answers to these urgent questions about this

Franco-Rhenish king:

|

|

| 1. |

May a clerical raconteur punish

Theuderic

with a certain portion of ignorance, since he has taken him for

a son of any heathen concubine?

|

| |

|

| 2. |

Has that skilled young man kept

a respectable distance to his rude and bloodthirsty father?

|

|

|

|

Fact is that King Clovis could rely

on Theuderic for daring missions, e.g. against the

Visigoths. On the subject of this operation, the history reveals

that only the powerful appearance of Theoderic the Great

could stop the conquests made by Theuderic in 507/508.

Nonetheless, we may wonder whether or how much Gregory did

discriminate him against Clovis' sons Chlothar,

Chlodomer and Childebert, whose mother was the honourable

Saint Clotilde (Chrodechildis, Chrodigildis)

of Burgundian dynasty; and we may also wonder

whether Theuderic trained his skilfulness and sophistication by

keeping out of Clovis' gory ways. Thus, we may

consequently

ask: Did that young-aged man rather turn to an adventurous eastern

border area of the Franks? We may assume that he

could have received a certain part of Rhenish territory as

operation base and place of residence from his father and/or the

local leader of this area – that large region which Theuderic

actually inherited later as an important part of eastern Frankish

kingdom. The

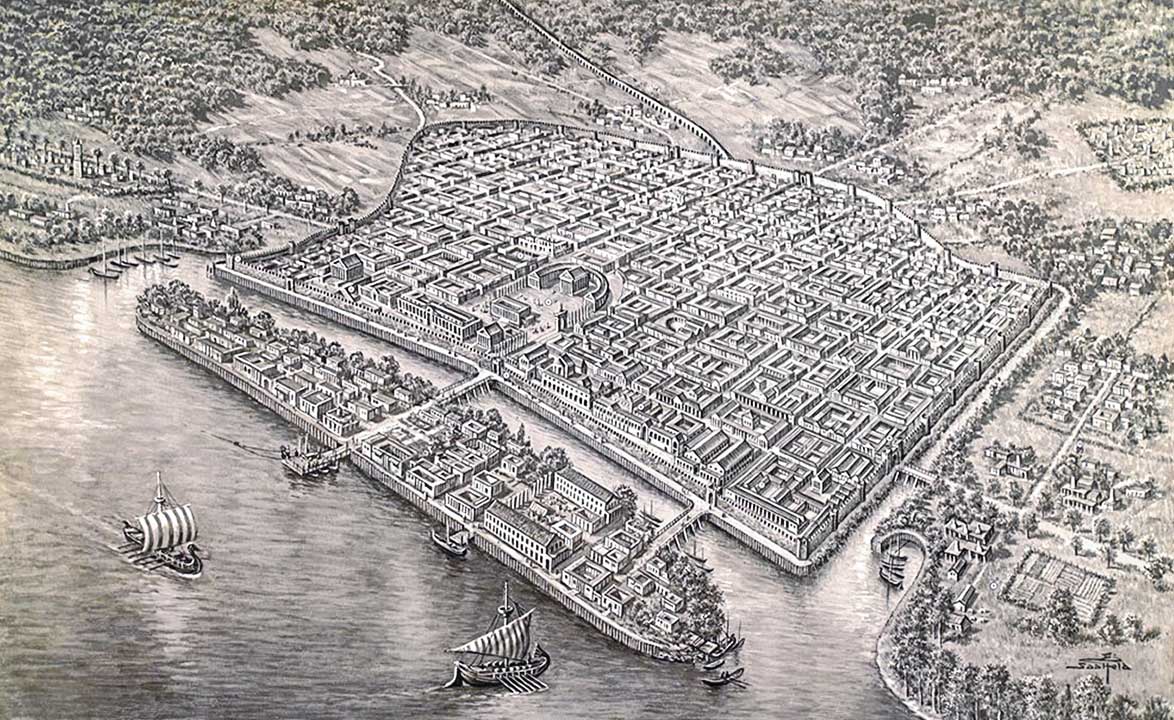

territory between the German towns Aachen – Cologne – Bonn –

Zülpich was an excellent geographical centre

of an area that was called later Ripuaria, and a good place for

Theuderic ‘and’ Thidrek to

start an exiting exploration into the dangerous depth of miraculous

woodlands beyond the Rhine, where all those Roman Eagles were driven

back or torn into bits and pieces just a few centuries ago. A regnal

seat in this Berner Reich was not too far from important

economic locations on the Rhine, e.g. such as the Confluentes

(Koblenz), and it was also a good place for King Thidrek

to ride out

to his good friend King Atala who was residing some dozen miles

away at one of the most important settlements on a territory of today’s

Westphalia: Susa–Susat–Soest. The form

‘Attila’ appears as a popular derivation of a genuine

Atala bearing the diminutive form of the

(Proto-)Indo-European ā̆tos, atta = father.

He is

spelled ‘Aktilius’ or ‘Atilius’ in the Old Swedish manuscripts, and

also ‘Attala’ in Icelandic MS B.

However, turning again to both

questions above, we are leaving at this point Gregory’s Frankish

horizon of recitation for real barbaric outland.

|

|

| 3.

Some literary and historical environments |

|

|

3.1 Gransport

|

|

|

The manuscripts report

that one day King Ermenrik expelled Thidrek from his Bern

residence. He immediately fled to King Atala’s

for

that reason. After ‘20 years’ (cf.

Ritter by counting up these ‘20 years’ to c. 515)

Thidrek goes out to meet martially his kinsman Ermenrik.

Thidrek’s messengers finally find him at Roma II

(Trier on the Moselle) where Ermenrik, being informed likely earlier

than expected, prepares the counter-attack (Sv 272–273, Mb 322–323). As

all manuscripts unmistakably provide,

Thidrek has to take big losses in the battle on that location on the

Moselle

location which the literati call ‘Gransport’,

‘Gränsport’ or

‘Gronsport’.

The location of this battle appears on the Moselle farther downstream

from Trier, where the ancient TRAVENNE

was understood as the Italian Ravenna by the southern Dietrich

Epics poets, see August

Wilhelm Krahmer, Die Urheimat

der Russen in Europa und die wirkliche Localität und Bedeutung der

Vorfällen in der Thidrekssaga. Eine frühe Auseinandersetzung

über die realen Hintergründe der Thidrekssaga (Moscow

1862).

Traben (Traben-Trarbach) is certified in 11th and

12th century as Travena, Travana,

Travina, Travene, Traven and Travenne,

just in an area where the Moselle could swell into a huge lake (cf.

Krahmer), where remains of Roman buildings and a Frankish burial ground

were found, where the castle called Grevenburg

is 5 km far from Bernkastel; cf. Wolfgang Jungandreas, Historisches

Lexikon der Siedlungs- und

Flurnamen des Mosellandes (Trier 1962–1963) pgs 1040–1043.

Ritter, however, decided on Rauenthal at the mouth of the

Moselle.

It seems not unproblematic to chronologize Thidrek’s campaign

against Ermenrik without

further contextual explorations (see farther below).

The writers of the Old Norse + Swedish texts

connect the age

of Thidrek’s brother Þetmar/Detmar,

aged ‘20 years’

at that time,

with the interim period of exile. However, it appears less

believable that Thidrek would have waited two decades for

the first real opportunity to regain his kingdom.

Since Sv 355 and Mb 413, both the last chapters

numerically taking up Thidrek’s expulsion, allow to check

again this span for a redating (see farther below),

the more or less questionable age of his alleged brother might have

inspired the primordial narrator to enlarge Thidrek’s interim

period of exile.

|

|

|

|

Although

Ferdinand Holthausen

(Studien zur Thidrekssaga, in: Beiträge zur

Geschichte

der deutschen Sprache und Literatur, PBB, Band 9, Heft 3; pgs

451–503) quotes those

Italian localizations which are out of both historical and

historiographical probability, he proposes Gransdorf (see p. 482) on the

Moselle. However, the ‘Gänsefü(h)rtchen’,

diminutive form of ‘Gänse-furt’, is an evident historical nickname

of a notable historical rapid localized nearly one mile before the

Moselle’s mouth.

Ritter underlines that this name cannot originally derive from ‘a

ford that geese (Germ. ‘Gänse’) formerly used to cross the river

at that very place’. He rather estimates the concave rock of the

rapid filled or covered with stony ‘grant’ (cf. En. ‘gravel’,

‘granule’) for

the original name based upon spelling like ‘Grantfurt’.

Ritter also notes well that ‘Rauenthal’ (Raven →

Raben -tal) may indicate rather the more believable historical location

for detracting epics

dealing with the battle known as the Rabenschlacht.

|

| |

|

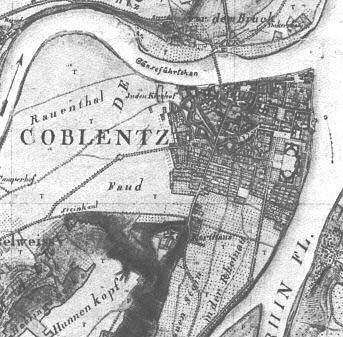

This

cartographic detail is provided by the map of Tranchot & von

Müffling, 1806. The rapid’s name and

position was added by Ritter who refers to the research of Fritz

Michel, eminent local historian of Koblenz.

|

|

|

|

CONFLUENTES:

The panoramic copperplate engraving by Möbius (1820)

provides a view from the east bank of the Rhine to the hills

of traditional ‘Hunnenkopf’ (‘Huns Head’ field) on the

left. The Moselle’s mouth on the right appears as a lake

(Germ. ‘See’) in high-water times. See also the author’s

comprehensive article catalogued at the National German Library

DNB: Die

Mosel im Licht von Thidrekssaga und Dietrich-Chronik.

|

|

|

3.2 Some historical

and

literary

analogues

| 1. |

Thidrek’s

ancestor Samson started his expansive politics from the same area as

Childeric I:

northeastern Gaul. Samson’s region included ‘Appolij’ (not

Apulia!), nowadays rather the Dutch Peel north of the Hesbaye which

is neither southern ‘Hispania’ nor Spain (!), as the authors of the Old

Norse + Swedish texts certainly provide Hispania

between the western foreland of the Eifel and the northern fringe of

the silva carbonaria, a woodland frequently mentioned in Roman

and Frankish

historiography. Furthermore, the scribes of these manuscripts have

connected Samson with an obvious geonymic ‘Salerni’, which seems to

express a corresponding relation to the region of the Salian Franks.

According to Ritter’s timeline of events provided by these

transmissions, this Samson

appears as a contemporary of this Childeric whose

grave was found east of the ‘charcoal wildwood’.

|

| |

|

| |

The writers of the Old Norse

+ Swedish texts relate in their early chapters

that Samson seduced the daughter of an influential ruler and went

with her into an interim refuge for that reason. We also remember

well that Gregory of Tours has ascribed a quite similar delicate

affair to Childeric in a northeastern 5 th-century

Gaulish region. The Old Norse

and Swedish scribes also note well that Samson had remarkable

black hair and an impressing beard.(7)

He slew two noble brothers of ‘Salerni’, the literary Salvenerias

by Ritter’s suggestion which, however, may represent nothing

more than generally the Salian region. Mentioned as dux and

king of ‘Salerni’, at that time already grey-bearded, he decided to

move martially to the Rhine-Eifel lands, as this region appears

contextually more plausible than any venue on an Italian territory.

From there, as the texts further relate, he impudently demanded 12

free-born virgins, the daughter called ‘Odilia’ of

the Bern ruler, and some other

tributes from him. |

| |

|

| |

Childeric’s place of

burial has been assigned to his seat in that region of his

likely early activities which extends from Tournai to Lys river. Thus,

the distance between this region and

the venues of Samson seems less significant

with regard to the spatiotemporal movements in Gaulish Migration

Period and the geographical understanding or knowledge of the

Old Norse and Old Swedish writers.

|

|

|

| 2. |

Samson, accompanied by his son

and successor Ermenrik, died on his martial way to Roma II,

as this concourse of circumstances was expressively remarked by Ritter.

Rather accordingly, Childeric died at that time when the Franks

were capturing Trier on the Moselle.

|

|

|

| 3. |

In 486/487, for the first time,

Clovis had good reason to call

out ‘Great Kingdom of the Franks’ after the martial removal of

Syagrius, last ‘post Roman governor’ of Gaul. Shortly before and

after this

event, as contextually deduced by Ritter, Ermenrik called in his

kinsmen, tribal leaders and some mighty followers

to his first and second ‘Imperial Diet’, a colloquium of obvious

Frankish leaders and some jovial guests at the Roma ‘cisalpina’.

|

| |

|

| |

‘Imperial Diet’:

I: Sv 124, more in detail: Mb 123–124.

II: Sv 227, Mb 269.

See HISTORIA

WILKINENSIUM, THEODERICI

VERONENSIS…

provided by J. Peringskiöld, ch. 100 (Mb 123):

Convivii magnum apparatum, regia pompa

celebrandum, instituerat Ermenricus, convocatis ad eam solennitatem

primariæ dignationis viris

ex principum, Jarlorum, comitumque…

|

|

|

| 4. |

The third redactor of the Membrane

makes use of an individual spelled Salomon in order to show

that the Frankish realm had already extended to the Rhineland .(8) |

|

|

| 5. |

As Gregory of Tours narrates

events between c. 488 and c. 492, King Clovis slew his cousin

Ragnachar, king of Cambrai on the Schelde (‘Scheldt’). Apparently

anticipating this

action of eliminating awkward Frankish chiefs and their potential

successors, Sv 231–233 and Mb 278–280 remark the insidious removals of

Ermenrik’s sons Frederik, Regbald and Samson. As the texts provide,

Ermenrik was induced to tolerate

them no longer by counsel of his advisor ‘Sifka’.

Regbald, ordered to a mission apparently to the

Anglo-Saxons and thus needing a watercraft, had to choose between

three ships for that passage. He sank on most ramshackle ship

deceitfully offered to him as best of all. Was it Frankish

kingdom of already believable force to demand tribute from a ruler

who was obviously dwelling in ‘Ængland’ as an Anglo-Saxon

territory? For potential or rather likely interest of the Merovings in

tribal regions between Jutlandic-Danish area and East Anglia

see Ian N. Wood, The Merovingian North Sea

(1983); id., The Channel from the 4th to the 7th Centuries AD,

in: Maritime Celts, Frisians and Saxons, ed. by

Seán McGrail (1990), pgs

93–97.

|

| |

|

| |

James Campbell, The

Anglo-Saxon

State, London 2000, p. 75, states on Wood’s notions that he

|

| |

|

| |

brings

out some of the connections between Merovingian Gaul and Britain,

including the

possibility of Merovingian overlordship over parts of England.84

He suggests that a factor in these may have been

Merovingian control

over the Frisian coastline for a substantial period. This could, of

course, have had important significance in relation to East Anglia and

raises important questions about Frankish sea power.

__________________

84 Ian N. Wood,

The

Merovingian North Sea (Alingsås, 1983).

Wood’s arguments have been also reviewed by Irene Bavuso, Balance

of power across the Channel: reassessing Frankish

hegemony in southern

England (sixth–early seventh century), in: Early Medieval Europe

(2021) 29 (3) pgs 283–304.

It should be noted for further estimations also Wood’s article Frankish

Hegemony in England, in: M.O.H. Carver

(Ed.), The Age of Sutton Hoo: The Seventh Century in

North-Western Europe (1992) pgs 235–242.

|

|

|

| 6. |

While Gregory mentions

Theuderic’s service for King Clovis in 507, Thidrek supported

King Ermenrik against an obvious southeastern leader called

‘Runsteinn’ or (Lat.) Rimsteinius, whom Ermenrik wanted to

punish for outstanding tribute, see Sv 144 and Mb 147. Ritter

chronologizes this border war between eastern Franks and

Alemannians at the end of 5th century. At

this point we may remember Gregory’s passages dealing with

Alemannic-Frankish war, whose battles were apparently going on for

several years on some more locations than the region of Zülpich,

where King Sigibert of Cologne was wounded and

became lame.

|

| |

|

| |

A leader called Alpkerus,

ruler of a territory on the Danube in 6th

century, is

mentioned as filium Rŏsteini in the manuscript De

Origine Gentis Swevorum, in: MGH SS rer. Germ. in us. schol. 60,

p.

161.

|

|

|

| 7. |

While King Clovis passes away

after possibly 511, as the chroniclers do not

mention any attempt on his life, King Ermenrik dies of an abdominal

disease apparently caused by obesity, cf. Sv 345 and Mb 401.

|

| |

|

| |

Ian

N. Wood, an author

of the RGA (Reallexikon

der Germanischen Altertumskunde), does critically review

scholarship’s

estimation on Clovis' date of death in his paper Gregory

of

Tours and Clovis, in: Revue belge de philologie et d’histoire

63

(2) 1985, pgs 254–255:

|

| |

|

| |

That Gregory himself

was faced with an absence of trustworthy dates

in his sources can be seen clearly in his attempts to compute the date

of Clovis' death. Clovis, we are told, died five

years

after

Vouillé, that is in 512; eleven

years after Licinius became bishop of Tours, which apparently gives a

date of 517 or later; and one hundred and twelve years after the death

of Martin which comes to 509(35).

Gregory’s later computations on the deaths of Theudebert and Chlothar(36),

however, and the regnal dating for the fifth council of Orleans(37)

seem to require an obit for Clovis of 511–2.

Nevertheless before

accepting this, it is worth recalling the fact that the king was

clearly alive at the time of the

first council of Orleans which consular and indictional dates place

firmly in 511(38).

Moreover the Liber

Pontificalis records Clovis' gift of a

votive crown

to the shrine

of St. Peter in the pontificate of Hormisdas, in other words between

514 and 523(39).

Although

the weight of the evidence does suggest that Clovis died in late 511 or

512 the chronological confusion in Gregory’s attempts to calculate this

can only imply that the bishop did not have reliable evidence on which

to base his computations. This coincides with the conclusions suggested

above, that Gregory’s known sources would have provided him with no

dates, and it means that even the most general chronological

indications in the second half of Book Two of the Libri

Historiarum, with the possible exceptions of the quinquennial

dates for the defeat

of Syagrius and the Thuringian war(40),

are invalid as historical evidence.

__________________

(35) Gregory, Liber

Historiarum, II, 43.

Licinius' predecessor was still alive at the time of the

council of

Agde in 506, to which he sent a representative; see Concilia

Galliae, A 314-A 506, ed. C. Munier, Corpus Chrislianorum

Series

Latinorum, 148 (Turnholt, 1963), pp. 214, 219. For further problems

on Licinius's chronology see Weiss, Chlodwigs Taufe,

p. 17.

(36) Gregory, Liber Historiarum, III, 37 ;

IV, 21. W. Levison, Zur Geschichte des Frankenkönigs

Chlodowech, in Aus rheinischer und fränkischer

Frühzeit (Düsseldorf, 1948), p. 208.

(37) Orleans, V (549), Concilia Galliae A

511-A 695, ed. C. de Clercq, Corpus Christianorum Series

Latinorum, 148 A (Turnholt, 1963), p. 157. Levison, Zur

Geschichte des Frankenkönigs Chlodowech, p. 208.

(38) Orleans, I, ed. de Clercq, pp. 13-5(?)

; Levison,

Zur Geschichte des Frankenkönigs Chlodowech, p. 208.

(39) Liber Pontificalis, ed. L. Duchesne

(Paris, 1955), LIIII.

(40) Gregory, Liber Historiarum, II, 27.

Two further quinquennial dates appear in some manuscripts only ;

Liber Historiarum, II, 30, 37. The authenticity of these dates was

defended by Levison, Zur Geschichte des Frankenkönigs

Chlodowech, pp. 205-7 and denied by Weiss, Chlodwigs Taufe,

p. 16. |

|

|

| 8. |

Thidrek goes martially

out

to take revenge for severe humiliation, his expulsion from Bern

by his kinsman Ermenrik, just about that time when King Clovis seems no

longer living or mighty.

|

|

|

| 9. |

Immediately after the

Soest Battle, as the texts provide, Thidrek moved to Bern

and recruited an army that won the decisive battle against

‘Sifka’, advisor of the apparent late Ermenrik, on location called Greken,

Graach on the Moselle in the Palatinate of Rhineland.

|

|

|

| 10. |

After the conquest of Roma

Thidrek certainly rose to a mighty leader of Frankish kingdom.

This is the version from the Old Swedish manuscript,

Sv 356:

|

| |

|

| |

He

rode into Roma,

got off his horse, went to take the same seat on which kings are

inured to sit and to be crowned … Hillebrand and Alebrand crowned him

and

appointed him King of the great realm that King Ermenrik had had

before… |

|

|

| 11. |

According to the Old Norse +

Swedish texts (Mb 426–428, Sv 367–369), Thidrek

took over a

region which covers parts of the later North Rhine-Westphalia and Low

Saxony after the death of Atala who had

lost

there many of his male subjects in

the Soest Battle which Ritter has dated into

6th century.

|

| |

|

| |

This

context does correspond with ethnographical and archaeological

studies which provide the Merovingian

Franks moving to the aforesaid regions and parts of the later

Hesse, Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt.

|

|

|

|

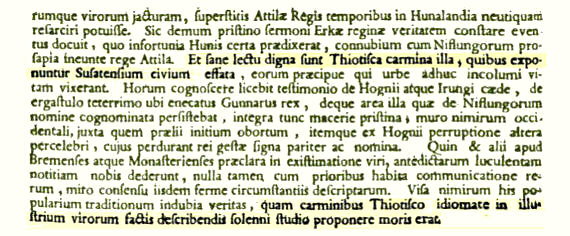

Clip from Latin text provided by J.

Peringskiöld: the beginning of ch. CCCLXXX, cf. 10th

item above.

Clip from Latin text provided by J.

Peringskiöld: the beginning of ch. CCCLXXX, cf. 10th

item above.

|

3.3 Theuderic’s

provenance and disappearance

after 507

It seems

noteworthy that both Theuderic’s and Theoderic’s name is

basically related to a composition of the Gothic þiuda (= grouping of peoples or

tribes as a ‘nation’,

cf. ‹ Proto-›

Indo-European teuta

plus reiks [=

‘rich’ + ‘ruler’, cf. ‘reign’] ), while the form *þeudō,

the generic root estimated for Ur-Germanic language, may encompass the

prime form also for the

etymology of the later term deutsch (cf. also

the

[Lat.] Teutones, a Germanic ‹ or

Celtic? › tribe

presumably related with the

Jutlandic

Thy).

Ritter-Schaumburg

estimated the birth

of Thidrek about 470, whereas Frankish king Clovis is believed

to be

born a half decade before him. This constellation

may appear as predominant item contradicting Thidrek’s

literary reflection of Frankish king Theuderic I.

Therefore, reviewing

research regards both Ritter and the Frankish chroniclers'

genealogy about the early Frankish kings Meroveus, Chlodio and

Childeric as (at least) either less reliable or insufficient. As

Gregory of Tours remarks in his Decem libri

historiarum, he

has no solid pedigree information especially about these

Frankish-Merovingian kings, and so he had left a meagre ‘Some People

say’-phrase in this records.

|

|

|

Widukind of Corvey calls in his Rerum gestarum

Saxonicarum libri tres the Frankish

Theodericus (= Theuderic I)

a descendant of Huga, but neither ‘Clovis’ nor another ancestor

or

progenitor of the Franks. He thus follows an obviously

different line of genealogical tradition than

Gregory, who himself concedes to be referring to oral tradition for the

early

Merovingians. Although his genealogical suggestion of Theuderic’s

father cannot be validated anywhere, a large part of the ‘communis

opinio’ just converts unreliably Widukind’s genealogical statement to

«Clovis'

second name».

The chronicler of the Annals of Quedlinburg (see ch. 4

with source reference), less scolded than Widukind for

‘infidelity to history’, specifies Theuderic under a progenitor

epilogue that appears based on Widukind’s transmission:

|

| |

|

Hugo Theodericus iste

dicitur, id est Francus, quia olim omnes Franci Hugones vocabuntur a

suo quodam duce Hugone.

|

| |

|

[Hugo Dietrich

is called this one, who is a Frank, because once

all Franks were called Hugones after their leader named Hugo(n).]

|

|

With Gregory’s Merovingian

projection the Quedlinburg annalist,

most likely female, intervenes in Widukind’s version of

Theuderic’s ancestor by means of the Liber

Historiae Francorum to

which she obviously must have had an access, cf. Martina Giese who

rejects the usage of the elder books of Gregory at Quedlinburg (Giese, op. cit. p. 140 note 366).

Nevertheless, the annalist wanted to forward the quoted passage, (most)

likely because she already knew that any Huga or Hugo(n)

is neither convertible by means of

Frankish chronicles nor at hand of Gallo-Roman sources about

Theuderic’s ancestry.

Gregory remarks Theuderic’s son

Theudebert being already sturdy at a time when Clovis died; see libri historiarum (hist) III,1.

Regarding Thidrek’s as well as Theuderic’s bloodline over a

band of three generations, all male names being recorded are strikingly

beginning with ‘Th’ but not with any other letters.

Theuderic’s line (Theuderic → Theudebert → Theudebald)

is outstandingly unique with a view to all the other early

Merovingian branches wherein we typically meet kingly names

formed with capital ‘C’.

Regarding Gregory’s claim that a concubine

of Clovis I

should have been

the mother of Theuderic, a significant parallel between the latter and

his Ostrogothic namesake has long been pointed out. Matthias Becher

reasonably constates:

|

| |

|

Im Übrigen war

auch

Theoderich der Sohn einer concubina; seine

Mutter Ereleuva war vermutlich eine katholische Römerin, weshalb

eine Vollehe mit seinem Vater Thiudimir nicht möglich gewesen war.

An diese Möglichkeit wäre also auch zu denken, wenn man

über die Mutter Theuderichs nachdenkt.

|

| |

|

(Matthias

Becher, Chlodwig I. Der Aufstieg der

Merowinger und das Ende der antiken Welt (2011) p. 169.)

|

| |

|

[By the way,

Theoderic was also the son of a concubina. His mother

Ereleuva was presumably a Catholic Roman, and therefore a full marriage

with his father Thiudimir had not been possible. So this possibility

would also have to be considered when thinking about Theuderic’s

mother.]

|

|

|

How credible sounds the coincidence

that two contemporary kings with

the same Latin name should come from both a

‘concubinate’? How convincing appears Gregory’s view on Theuderic’s

origin, to which he does not even provide a resilient annotation to the

age difference between him and Clovis? Why should Clovis, who obviously

had no lack of legitimate sons, bequeath the largest part of his empire

to a son of a concubinage that was apparently quite far back in time?

Regarding Gregory’s insufficient and questionable

early Merovingian origin relations, apparently based on his conception

of ‘work-fair’ genealogy of Clovis' line up at least

to Childeric, it is by no means excluded that he borrowed from the

Ostrogothic

ancestry!

Consequently, the Low German source provider and/or the Old West-Norse

editors of the Thidrekssaga could have then concluded that

Þetmar II

was also Thidrek’s father.

However, it is not only the uncritical adoption of Gregory’s accounts

by younger chroniclers that nourishes doubts about Theuderic’s true

father.

Matthias Becher raises this objection (op. cit. p.

273):

|

| |

|

In diesem Zusammenhang

verdient eine

Quelle Beachtung, die von Gregors

Darstellung abweicht. In der Vita sancti Chlodovaldi – der im 9. oder

10. Jahrhundert entstandenen Lebensbeschreibung eines Chlodwig-Enkels –

heißt es, Chlodwig habe sein Reich seiner Gemahlin Chrodechilde

mit den drei Söhnen Chlothar, Childebert und Chlodomer

hinterlassen und unter diesen aufgeteilt. Eine Teilung durch den Vater

ist indessen sonst nirgendwo bezeugt. Weshalb ist der Vitenschreiber,

der sonst Gregor von Tours fast wörtlich folgte, ausgerechnet in

diesem Punkt von ihm abgewichen? Die Frage muss unbeantwortet bleiben,

doch auch wenn diese Quelle insgesamt als wertlos gilt, gibt ihr

Bericht in der Einzelfrage, die für ihren Autor im Übrigen

nicht weiter von Belang war – so dass er etwa um einer speziellen

Argumentation willen hätte abweichen müssen – doch zu denken.

In diesem Zusammenhang ist auch die Beobachtung der regionalen

Verteilung der Bischöfe von Interesse, die am Konzil von

Orléans teilgenommen haben: Der Osten, grosso modo Theuderichs

Anteil, war nicht repräsentiert [...] Ging es also bei Chlodwigs

Tod tatsächlich nur noch um die Frage der Aufteilung des

verbliebenen Gebiets unter seine jüngeren Söhne?

[In this context, a source deviating from Gregory’s account deserves

attention. In the Vita sancti

Chlodovaldi – the biography of one of

Clovis' grandsons, written in the 9th

or 10th century – it is said that

Clovis left his kingdom to his wife Clotild with the three sons

Chlothar, Childebert and Chlodomer, and divided it among them. However,

a division by the father is nowhere else attested. Why did the author

of the vita, who otherwise followed Gregory of Tours almost

literally, deviate from him in this point of all things? The question

must remain unanswered, but even if this source as a whole is

considered worthless: Its report on the individual question, which

incidentally was of no further importance for its author – so that he

would have had to deviate, for example, for the sake of a special

argumentation – still gives food for thought. In this context, the

observation of the regional allocation of the bishops who

participated in the Council of Orléans is also of interest: The

East, grosso modo Theuderic’s share, was not represented (...) So, at

Clovis' death, was it really only a question of dividing

the remaining

territory among his younger sons?]

|

| |

|

|

In fact, Theuderic is not mentioned

anywhere

in the Vita sancti

Chlodovaldi, which was written in 9th

or 10th century, and indeed it

does give pause for thought why its hagiographically adroit author

systematically passed him over. Clodo(v)ald is

supposed

to have been born around 520 and was thus still a contemporary

of Theuderic. Fluduald, as the former is called as a saint also in

later sources, appears as the third and youngest son of the Merovingian

king Chlodomer, who is considered the second eldest son of Clovis and

Clotild.

The knowledge of the vita writer about Clovis points to the facts

that he must have had

knowledge at least of Gregory’s historical works and thus deliberately

ignored Theuderic. Implicitly, however, it cannot be excluded in this

respect that Clovis could have desired the kingship of Theuderic – as

here

the postulated descendant of another Frankish dynasty – and, at a

certain point in time, could have taken it over. It has been plead for

an deliberate embezzlement of Theuderic by the writer of Clodoald’s

biography, but the weak argument that he intentionally disregarded

Theuderic because of his ‘less noble’ origin seems less convincing

compared to the fact that not one dignitary

from Theuderic’s (hereditary) kingdom appeared at the First

Council

of Orléans, which was convened by or for Clovis. Rather,

this

constitutional context speaks straight

at least for a

territorially isolated status of Theuderic at this time. Moreover, it

is

especially thought-provoking that neither Clovis'

Baptist Remigius

nor a deligated deputy from the former Belgica II

(Church of Rheims) showed up at

this constitutively highly significant synod. Thus Becher’s next

important observation is (op. cit. p. 250):

|

| |

|

Aber vor allem ein

berühmter

Bischof fehlte: Remigius von Reims – und nicht nur er, sondern

überhaupt kein Bischof aus dem Osten des Reiches war nach

Orléans gekommen. Man wertet dies als Hinweis auf eine

zunehmende Entchristlichung dieser Gebiete. Die Bischofsstühle von

Köln und Mainz etwa waren vakant. Dies reicht als Erklärung

nicht aus, denn etwa auch der Bischof von Trier oder der von Sens und

viele andere fehlten in Orléans. Es waren also auch Gebiete

nicht repräsentiert, in denen die Kirche durchaus noch

funktionsfähig war (...) Es fällt auf, dass die Gebiete, die

in Orléans nicht durch

ihre Bischöfe repräsentiert wurden, nach Chlodwigs Tod an

dessen ältesten Sohn Theuderich fallen sollten. Hatte Chlodwig ihm

diese Gebiete vielleicht bereits zu Lebzeiten als Herrschaftsbereich

anvertraut? Oder hing die Absenz der Bischöfe aus dem Osten des

Reiches mit den Wirren zusammen, die durch die Unterwerfung der

kleineren fränkischen Königreiche – insbesondere der

rheinischen Franken – unter Chlodwigs Herrschaft ausgelöst worden

waren?

[But especially one famous bishop was missing: Remigius of Reims – and

not only he, but no bishop at all from the east of the empire had come

to Orléans. One interprets this as an indication of an

increasing

de-Christianization of these areas. The bishoprics of Cologne and

Mainz, for example, were vacant. However, this is not sufficient as an

explanation, because the bishops of Trier and Sens and many others were

also missing in Orléans. Thus, areas were not represented in

which the

church was however still functional (...) It is noticeable that the

territories which were not represented by

their bishops in Orléans were to fall to Clovis'

eldest son

Theuderic after his death. Had Clovis already entrusted these

territories to him as a domain during his lifetime? Or was the absence

of the bishops from the east of the empire related to the turmoil

caused by the subjugation of the smaller Frankish kingdoms – especially

the Rhenish Franks – under Clovis' rule?]

|

| |

|

|

But why did not come Clovis'

Baptist Remigius of Reims? Already these questions point

to the highly questionable political-constitutional

condition that under Clovis the Auvergne (!) with bishop Eufrasius was

represented on this confessionally reformist as well as long since

socio-political summit on the one hand, but on the other, however,

Theuderic brought this part of the Frankish kingdom under his

rule after Clovis' death, to wit about

Theoderic’s death (526

!), with

considerable military force, cf. Gregory hist.

III,12–13.

As Gregory states earlier in hist. II,37,

Theuderic is said to have martially moved on behalf of Clovis

against the Visigothic cities Albi and Rodez, then marching to the

Auvergne, over which he

apparently held sway until it was taken over by Clovis. Until the

Council of Orleans (in the summer of 511), an Auvergne protectorate of

the Ostrogothic Theoderic therefore seems unlikely. Nevertheless,

Gregory’s later dating in hist. III,21

gives food for thought that the Visigoths

after Clovis' death – since 511 Theoderic was de facto

ruling

over them after Gesalec’s expulsion (!) – made remarkable

reconquests.

We may thus assume that the well-read author of the Vita

sancti Chlodovaldi

contradicts per ‘argumentum e silentio’ Gregory’s

genealogical inclusion

of Theuderic among Clovis' sons. Their closest

relationship had gained

its unimpeachable corona

because Gregory was undoubtedly the dominant source for the Chronicle(s)

of Fredegar and the Liber Historiae

Francorum, which was then

trusted by the Quedlinburg Annalist (QA) and copying chroniclers.

Therefore, the question of the division of

the Frankish kingdom among Clovis' sons, which Matthias

Becher posed

and which he tried

to point out openly, will have to be queried against the background of

a kingship claimed by Theuderic and insofar by his

line of descendants.

|

Theuderic’s mission to the Visigoths

to

satisfy Clovis, a campaign

in 507/508 with sizeable territorial gains which, however,

were stopped and massively reverted by Theoderic the Great,

is related to that very time-frame of approximately one

decade where Thidrek was expelled according to Ritter’s

rough estimation.

Regarding the

ambitions of Ermenrik, rivaling Frankish relative of Thidrek

and mighty ruler of Roma II – the

metropolis that only a short time before was known as

largest colonia on the north side of the Alps –, consequently

might have had good reason to follow Theoderic’s

standpoint and decision to put or see the Frankish Theoderic

in an isolated position. Ermenrik’s advisor ‘Sifka’ was

contributing this significant speech before Thidrek’s

expulsion; see Mb 284 and Sv 238:

|

| |

|

Mb 284:

One time King Erminrek called Sifka to counsel and Sifka

spoke to the

king:

"Sir, it seems to me you should be wary of your kinsman, King

Thidrek of Bern. It seems to me that he is preparing some great deed

against you, because he is an unfaithful man and a great fighter. I

suspect that you will maintain or lose your royal power as a result of

his desire to fight. You will have to prepare to defend yourself. Since

he became king, he has expanded his kingdom in many places and has

reduced your kingdom. Who has tribute from Amlungland, which he took

with his sword, and which belonged to your father? It is none other

than King Thidrek, and he will not share it with you, and you will

never receive it as long as he rules in Bern."

The king

answered:

"What you remind me of is true; that land belonged

to my father, and I do not know whether it should belong less to me

than to King Thidrek, but I shall certainly take it."…

[Translation

by

Edward R. Haymes]

|

| |

|

Sv

238:

One day Seveke talked to King

Ermenrik:

‘It seems to me that you soon have to be on the

lookout for your relative, King Didrik of Bern. He is an

unfaithful man and a mighty fighter. Watch out for him, see that he

will not win your realm! He enlarges his realm every day, but thereby

he is making yours smaller. I have come to know that it is your due to

demand tribute from him.

Your father won this land with his sword!’

The king

answered:

‘My father was owner of this land as a whole and it is to be mine not

less than to be his one.’…

|

| |

|

[Translation:

Ritter-Badenhausen. The Old Swedish scribe does not mention the

‘Amlung(a)land’ which has been localized as the important region

between

the Meuse and the Middle Rhine, thus not far from Ermenrik’s Roma

secunda.]

|

|

|

Johan

Peringskiöld’s Latin manuscript, cap. CCLIX:

Apud Ermenricum regem

de rerum publicarum commodis in medium consulturus Sifka, multa

de Theoderico rege sermocinari exorsus est. Huius inprimis

potentiam formidandam maximopere Ermenrico; iam multa magna moliri

ipsum viribus confisum suis atque bellicarum claritudine operum,

de palma etiam regni cum Ermenrico haud dubio disputaturum.

Proinde non aliud magis idoneum sibi videri consilium, quam istud

præsens nunc

suggerendum. Nimirum, a suscepto regiminis

tempore primo regni sui fines majorem in modum augendo

extendisse Theodericum, etaim cum decremento commodorum ad

Ermenricum pertinentium. Amlungiæ quippe regno iustis

Ermenrici genitoris armis acquisito, vectigalium proventum omnem sibi

vindicavisse Theodericum, quasi iure quodam legitimo inposterum

retinendum. Rex, probe Sifkam

meminisse ait, paternæ

quondam possessionis fuisse

provincias istas. Quapropter etiam sibi, utpote qui legitimo prognatus

est thoro, æquis rationibus competere ius

easdem vindicandi terras…

|

|

It is obvious that these versions,

substantiating the background of Thidrek’s Flight Legend,

cannot be

sufficiently

based

even on a ‘saga’ about the historical vita of Theoderic the Great.

With respect to the accounts by the Thidrek saga and the

contextual probabilities or possibilities related to the

period of Clovis and

Theuderic I, the advisor of Ermenrik, mighty

ruler

at Roma II from 2 nd

half of 5 th century to ‘c. 526’ (by Ritter’s

estimation),

could certainly fathom that Theuderic–Thidrek

would be vulnerable if his South Gaulish campaign would be repelled.

Regarding this military expedition, Gregory dates

the removal of Sigibert of Cologne at (nearly) the same time.

He has been identified with King Sigmund’s son Sigurð(r),

Old Swedish Sigord,

the eminent champion who follows Thidrek as designated

brother-in-law

of the Niflunga rulers. The leaders of this folk

between the Meuse and the Middle Rhine, as situated by the manuscripts,

might have had good reason to accept and serve the expansion politics

of either Clovis or – as we can postulate alternatively with

intertextual consistency –

a potential loyalist at the former Colonia Treverorum for the

opportunity to administrate the northern Eifel lands of a

disempowered Thidrek.(9) |

Except for Deor’s

Lament, the

thirty to thirty-two years of exile are attested as Hildebrand’s period of banishment,

but only weakly to that of Dietrich

in the MHG epics; cf. esp. Hans

Kuhn, Dietrichs dreißig Jahre,

in: (Ed.) Hugo Kuhn and Kurt Schier, Märchen, Mythos,

Dichtung. Commemorative publication for

Friedrich von der Leyen, Munich 1963, pgs 117–120.

As Guðrún complains in the Guðrúnarkviða

III (in þriðja), Þjóðrek

had lost 30 warriors

in the fights of her brothers against Atli. Regarding this numerical

figure,

however, it is challenging but uncertain whether the source of this

tradition may subtly allude to rather the exile span of Dietrich

and Hildebrand.

Regarding Old German counting of years, however,

it seems apt to reassess Hildebrand’s remarkable exorbitant

time of outlandish exile as quoted in Mb 396. Before this,

however, we should

regard at the outset the measure of time we will be confronted with.

The manuscript versions published by J. Peringskiöld 1715 conveys

quotations that Hildebrand died at an age of either 180 or 200 years.

H. Bertelsen (op. cit. II. p. 359) transcribes

the passage of the obvious eldest text as halft annad

hunndrad wetra þa er hann anndaþist. enn þydersk

kuæde seigia ath hann hefdi .cc. wetra.

The German translator F. H. von der Hagen agrees with

Peringskiöld’s transmission and supplements at hand of the

Icelandic texts which are explicitly referring to German tradition.

According to Hagen,

these manuscripts specify Hildebrand’s age of death with 150 (MS

A) or 170 (MS B) winters,

see

Mb 415–416.

Hans-Jürgen

Hube follows Ritter’s explanation of this kind of number rendering on

the subject of half-years counting related to

the life of Hildebrand and, implicitly by the transmissions, Dietrich

von Bern; see

Ritter, Dietrich von Bern,

Munich 1982, p. 205f., 267; see Hube, Thidreks

Saga (Wiesbaden

2009) p. 354, ann. 1, accordingly Edo W. Oostebrink, Die Anfänge der Merowingerherrschaft am Niederrhein

(2017) p. 88. See also Hans Friese, Thidrekssaga

und

Dietrichepos (1914), who points out that ‘reckoning by

half-years is a natural Nordic custom’.

Thus, the corresponding passages of Mb

396 obviously admit to comprehend Hildebrand’s and

Thidrek’s «32 winters»

outside the country – Ek hæfi

nu latit mitt riki

.xxx. vætra oc ij vætr; (see

Bertelsen

op. cit. II, p. 331) – originally as the half of this sum (i.e. 16

years).

While the Latin redactor of Peringskiöld’s edition has modernly

equated winters with years in this instance, the

scribe of the ‘Didriks chronicle’ does not relay

the length of their exile (Sv 340–341). The time

span

provided by these

texts reiterates also the Jüngeres

Hildebrandslied, first attested in 15th

century. However, this special context

related to the time of Dietrich’s

and Hildebrand’s grief may not

automatically legitimize recalculations or halvings of other times

conveyed by the Old Norse

manuscripts and Old German traditions. Incidentally, the poet

of the 9th-century Hildebrandslied

knows of summers and winters sixty – line

50: ih wallota sumaro enti wintro

sehstic...

Did the oral provider and his listener or writer mean sixty or rather

sixteen?

The latter number seems plausible for an original period of ‘32

years’ based on 16 winters and 16 summers, as this

appears more acceptable in view of fast-changing relationships

of Migration Period. However, as quoted from Mb 415, there was

evidently confusion, at least among mediaeval authorship,

dealing with Hildebrand’s age. Furthermore, Ute Schwab (op.

cit. below, see p. 576) notes well that the Low German Hildebrandlied was transferred by a

linguistically less experienced Bavarian writer (!): Diese

verniederdeutschte Fassung des ‘Hildebrandliedes’ war von einem Baiern

durchgeführt worden, der nur die Faustregeln des

Altsächsischen beherrschte, also z.B. die hochdeutschen frikativen

Ʒ ‹ germ. t

wieder mechanisch zurückverschob, auch dann, wo kein Grund

dafür vorhanden war (suasat etc.).

Regarding the contextual interpretation of this apparent transcription,

obviously

made rushedly or at least extemporaneously at the monastery of Fulda

(in the later German state Hesse),

with the Old English Deor, Ute

Schwab underlines that [transl.] «the historicizing details

of the son’s

speech remain (intentionally) vague – nothing points to the return of

Dietrich’s army, to which Hildebrand is supposed to belong here

according to modern philologists – except the 30 years in the later

lament of the old man (...) This time does not agree with the saga

exile of Theoderic at all as naturally as is always claimed: only the

Old English ‘Deor’ (9th/10th

century) knows the 30 years of exile: (18–19) Ðeodric ahte

þritig wintra /

Mæringa burg; þæt wæs monegum cuþ (also

quoted below for further exploration). But the identity of this

Ðeodric, as well as the place where he ruled for thirty winters, is

not necessarily to be connected with Ostrogothic history: Kemp Malone

identifies this Ðeodric with the Frankish Þeodric of

‘Widsith’ (v. 24 Hugdietrich, king of the Franks; v. 115 Wolfdietrich

[?]). Thirty years – ‘sixty summers and winters’

– is, moreover, a period which elsewhere also means merely “long

years”.»

|

| |

|

Die historisierenden

Details der Sohnesrede bleiben (gewollt) vage – auf die Rückkehr

des Dietrichheeres, zu dem Hildebrand hier nach Auffassung der modernen

Philologen gehören soll, deutet nichts hin – außer den 30

Jahren in der späteren Klagerede des Alten (...) Diese Zeit stimmt

mit dem Sagenexil Theoderichs jedoch gar nicht so

selbstverständlich überein, wie immer behauptet wird: nur der

altenglische ‘Deor’ (9./10.Jh.) kennt die 30 Exil-Jahre: 18

Ðeodric ahte pritig wintra / Mæringa burg; þæt

wæs monegum cuþ. Doch ist

die Identität dieses Ðeodric und auch der Ort, wo er

dreißig Winter lang herrschte, nicht unbedingt mit der

ostgotischen Geschichte zu verbinden: Kemp Malone identifiziert diesen

Ðeodric mit dem fränkischen Þeodric des ‘Widsith’ (v. 24

Hugdietrich, König der Franken; v. 115 Wolfdietrich [?]).

Dreißig Jahre – ‘sechzig Sommer und Winter’ – sind überdies

eine Zeitspanne, die auch anderswo lediglich “lange Jahre” bedeutet.

|

| |

|

(Ute

Schwab, Waffensport, Rauba und

Dietrichs Schatten....

In: Neophilologus

84 (2000) pgs 575–607, see p. 581.)

|

|

|

Kemp Malone argues on Dietrich’s

time span of exile (op. cit. 1959, pgs 119–120;

highlighted passage

by the quoting author):

|

| |

|

There is no

statement in the Wolfdietrich, it is true, that the

hero possessed the burg of Meran for 30 years, but his stay

there, as child and young man, seems to have lasted some such time, and

30 is, of course, only

a conventional or “typical” number, used in Deor to

indicate a considerable

stretch of time, in Wolfdietrich to indicate a considerable sum

of money, in Beowulf to indicate unusual strength (379) or

prowess (123, 2361). Moreover, the important point to note is that the

hero’s stay at the burg is looked upon, both in Deor and

in the Wolfdietrich, as a period of misfortune, and this in

spite of the fact

that he is master there and well served (in the German story, it ought

to be

added, the hero’s legal overlordship begins only with Hugdietrich’s

death). As regards the faithful retainer, Schneider and Schröder

between them have shown that Berchtung of Meran belongs to Frankish,

not to Ostrogothic tradition, and that he is to be identified, in name

and function alike, with the Clarembaut of French story.10

In sum, the existence of an early and intimate connexion of Theoderic

the Frank with Meran can hardly be disputed, while we have no evidence

that Theoderic the Ostrogoth was ever thought of as living in exile

either in Meran or in any other place of like name.

|

|

__________________

|

| |

|

10. H. Schneider,

Die Gedichte und die Sage von Wolfdietrich (1913) and Germanische

Heldensage I (1928); E. Schröder, ZfdA LIX (1922) 179f.

|

|

|

As concerns the Old Norse + Swedish

texts, we

furthermore can stumble

upon Mb 413 and Sv 355 whose writers and heroes look apparently back to

the time

of Thidrek’s Gransport expedition:

Relating now the death of

Ermenrik’s advisor, he had survived his king certainly by some years,

both chapters provide a period of two decades

(vicennium, ch. CCCLXXIX Latin manuscript)

after the battle of Gransport.

The Icelandic redactions specify this time span, which ends by all

texts just before Thidrek’s

appearance in Roma II,

remarkably

shorter: MS A = ix , MS B

=

xi. This approximate halving seems to point to an attempt to convert

the ‘elder mode of counting years’ likewise, albeit both numerical data

are

still specified – apparently shortened – into winters only.

Regarding

this context in so far, the

second or last period of Thidrek’s exile, starting from his

military endeavour to regain his kingdom at Gransport, was

lasting not less than nine and not more than eleven years, as this

seems

plausible for even the entire exile period of rather 16 than 32 years.

Besides, the

Danish-born philologist Adolfine ‘Fine’ Erichsen

translated only the period given by MS A (Thule.

Altnordische Dichtung und Prosa, 22, Jena 1924). Thus, this

battle on the Moselle

can be dated between 510 and 515; cf. Ritter’s proposal about 515

by his rough

approach. Although estimations on the historicity of the latest

possible date of Clovis' death

should not be attested, at most compared with a Nordic historia

or ‘saga’, the Frankish Ermenrik seems to be still alive in this

stretch of time.

Furthermore, it seems noteworthy to reconsider the numeric

ascription of the Icelandic texts in Mb 429 where the scribe of MS B

may have rounded down slightly the period of Dietrich’s and Hildebrand’s

exile to xxx winters, see Mb 396. Regarding the difference of x

winters

left by the scribe of MS A at the same passage,

however, he has seemingly lost one decade character; cf. F. Erichsen

who consequently resigned her preference of this redactor for this

item!

|

|

|

3.5 Some

interliterary

receptions

|

|

Regarding Upper German traditions of

lesser connectedness for Dietrich contexts, the Waltharius

comes with an obvious 10 th-century account

about two champions known later as followers of Dietrich. This

work, most likely written by a Gaeraldus and presumably edited by Ekkehard

I at

Upper German St. Gall(en)

Monastery, seems to reflect Hunnic invasions from earlier times up to 10 th

century. Interestingly, the author of this lay calls his protagonists Guntharius

and Hagano heroes of

the Franks. This appears to be a smart

contemporary relocation based on 6 th–10 th-century

Frankish politics with a territory that actually encompassed Worms. It

may also seem

noteworthy that the Franks annexed

this and other location west of the Rhine to their territory after the

Alemannic Wars, thus even in 5 th

century; cf. e.g. RGA 9 (1995) ‘Francia

Rinensis’,

p. 372;

Eugen Ewig, Die Rheinlande in fränkischer Zeit, in: Franz

Petri, Georg Droege (Ed.), Rheinische Geschichte 1,2, p. 16f.

The Waltharius is also known as the poem

of Walter

and Hildigund. The Old Norse +

Swedish texts provide her as daughter of a Russian or Slavic ruler Ilias

and, according to the texts, female hostage at the court of the

northern Ata la; see

the coherent localization of Hildigund’s father Ilias

af

Gercekia by Hans-Jürgen Hube at ch.

Early activities in Baltic lands and Western Russia.

Hǫgni, trying to stop the fleeing two lovers, loses one

eye in the fight against Walter who later falls at Gransport as

Duke of Waskenstein – as this location appears also

transferable to the papally mentioned Vosca on the Lower

Moselle. It is obvious that the author of the Waltharius

implanted

thrilling elements in

his much embellished adaptation that some reviewer would judge

between ‘subtle’ and ‘oversubtle’. Ritter argues that the

archaic version

appears to be conveyed by the Scandinavian manuscripts of the

Thidrekssaga, see Sv

222–225.

The Latin text of the Upper German tradition, preserved at bibliotheca

Augustana, is available at

http://www.fh-augsburg.de/~harsch/Chronologia/Lspost10/Waltharius/wal_txt0.html

(retrieved

Aug. 2008). |

|

|

|

As already mentioned above, the Lament of Deor (10th

century, the Exeter

Book) conveys Ðéodríc’s

period at the ‘Mæringa burg’ as of thirty winters – the

author or his source supposedly neglecting the original ‘summers’

apposition. Deor likes to substantiate this relation:

|

|

(18–20)

Ðéodríc áhte

þrítig wintra

Máeringa burg; þæt

wæs

mongegum cúþ.

Þæs oferéode, ðisses

swá mæg .

|

Theodric had thirty winters

Mæringa burg; that was known to many.

As that passed away, so may this. |

The author continues with these lines (21–22):

|

|

Wé

geáscodan

Eormanríces

wylfenne geþóht; áhte

wíde folc

…

|

We learned of Eormanric’s

wolfish mind; he ruled people far and wide

…

|

Does the strophe of lines 18–20 provide a more

or less tendentious retrospective view to Þeodric’s

location of exile? Westphalian regions between the Rhine and Soest,

residence of King Ata la

by the Old Norse + Swedish texts, have been

estimated

historically under Mær(ov)ingian

rulership or administration in and after the first half of 6 th century.

Taking scope within Kemp Malone’s approaches, however, there might

be more interesting detections, e.g. of Þeodric’s outlandish

location

name which may be found in ‘old continental Saxony’ and, according to

the Old Norse + Swedish texts, in King Ata la’s

large kingdom.

Malone points out that those Myrgingas, the

tribesmen to which the writer of The Widsith

belonged, have been scholarly detected in continental Saxony, more

narrowly in southern Jutland which partially

belongs to modern Schleswig-Holstein. He furthermore remembers,

besides, that the Geographer of Ravenna has already situated (roughly

enough!) the Maurungavi

on the Elbe – patria Albis

Maurungavi

certissime antiquitius dicebatur – and adds that there was once the

frontier mark of the Franks (‘prima linea Francorum’). A Curtius

Moranga

in pago Morangano

appears connected

with the region around Hildesheim: The Vita

Meinwerci

episcopi Patherbrunnensis remarks on the life of the

meritorious 11 th-bishop

of Low German Paderborn a Bernwardo

Hildesheimensi

(…) quandam regiam curtem Moranga dictam, in pago Morangano, ch.

XXII. (Malone, Widsith,

Copenhagen 1962, p. 183–186 quoting i.a. Karl Müllenhoff,

1859, p. 279–280.) Müllenhoff’s

foregoing colleague Ludwig Ettmüller has been suggesting the form

‘Mar’ as common root of both ‘Mer’ and ‘Myr’ in this interlingual

context (Scopes vidsith, p. 11), whilst

Müllenhoff assesses ‘Maur’ and ‘Myr’ transposable, the latter even

in spite of the following ‘binding consonant’. As noted

farther below, he finally may be right on *myr

in the (phonetical) meaning of mire

– miry (adj.),

ON. mýrr, OE. mór,

German moor, Old Frisian mor. It may be worth

mentioning that the meaning of

Zoëga’s ‘ mæ ringr

(-s, -ar),

m.: a noble man‘

is not related to a tribal region in so far (Geir T.

Zoëga, A Concise Dictionary of Old Icelandic,

1910), while Jan de Vries (op. cit.)

places a

‘boundary mark or line’ at the disposal for the preferential

interpretation of ON. *mæ ri.

As regards the ruler called ‘Þiaurikr’ on the Rök

Runestone, see

endnote

6 i quoting from the Studies

(1959) of Malone,

who might clarify the geographical context for the castle

called Máeringa in Deor.

Thus, we obviously have no reliable source context to identify the Mæ ringa

with any forms which have

been suggested, less convincingly, from North Italian and Istrian

‘Merania’ by means of mainly Upper German poetry.

Raymond W. Chambers rejects Ettmüller’s and Müllenhoff’s

conceptual coincidence during his Widsith

analysis, claiming rather that the derivation of Mauringa,

Maurungani (cf.

Lat. Maurus = moor) from a

root

connected with O.H.G. mios, English moss and mire

‹ are› distinct from English

moor (…) which

is linguistically impossible (Widsith,

1912,

p. 160 & 236).

Nonetheless, Chambers presents a geographical version with overlapping Maurungani

and Myrgingas (op.

cit. p. 259).

Regarding another geographical approach, Alfred Anscombe prefers the

remark made by Paulinus of Nola who

knows of an obvious Gaulish terra

Morinorum

beside the English channel (Nola, Ep. 18.4).

Thus, we may re-estimate a

stronger relationship of these apparently concurring geonyms provided

by the Widsith, Deor and the Rök

Runestone.

|

| |

Besides:

If the translating scribes of the Thidrekssaga had mistaken

an

original form of Mæringar for their Væringiar

(Waringi at chs 13 and 17 in Johan Peringskiöld’s Latin

script), the annotations provided with Mb 13, 19, 69, 185 and 194 would

make more sense for narrating tribesmen living between the Rhine and

Jutland but not people originated in Scandinavia or Slavic regions; cf.

‘Värend’ location in Middle Ages. Bertelsen ascribes the

‘Varangians’ = Væringiar to ‘Nordic traveling

merchants’. As regards the apparently typical ‘g’ consonant,

these people should not have been mistaken as the Varini of

Tacitus or the Varni of Procopius or the Varinnæ

of Plinius. The War(i)ni have been frequently

identified with