|

|

|

When

the Frankish king Clovis came to

be baptized after his decision to convert to Christianity, Bishop

Remigius said

to him

Meekly bend

thy neck, Sicamber ...,

as predicated by the Gallo-Roman historian

Gregory of Tours, who gave on this occasion an example of his more or

less comprehensive knowledge

of Roman-Germanic history. Gregory’s original phrase provides book

II,31 of his Decem

Libri Historiarum:

Mitis

depone colla, Sigamber ...

| |

|

The

Baptism of King Clovis.

|

|

A partial

view of the altarpiece by the Master of Saint Gilles (abt 1500).

|

|

|

|

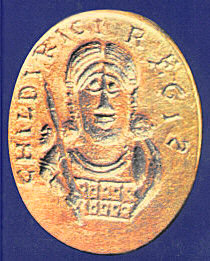

The

Seal Ring

of Childeric I, son of Meroveus and father of Clovis.

The

Seal Ring

of Childeric I, son of Meroveus and father of Clovis.

|

The

Sicambri, a powerful

tribe apparently migrating along the Danube and the Rhine,

were arriving presumably in the eastern region of the Lower Rhine in

the

period of Tiberius Caesar Augustus. Gregory of Tours might have

connected them with a ‘migratory legend’ somewhat related to that part

of land which was known to the Romans as Germania inferior and Belgica

inferior. Gregory

writes in book II,9 that

the

Franks came from Pannonia and

first settled on the bank of the Rhine; they then

crossed the river, marched through

‘Thongeria’, and set over them long-haired kings

chosen from the foremost and most noble

family of their race in every village ‹ ‘pagus’ ›

or city ‹ ‘civitas’ › ... |

|

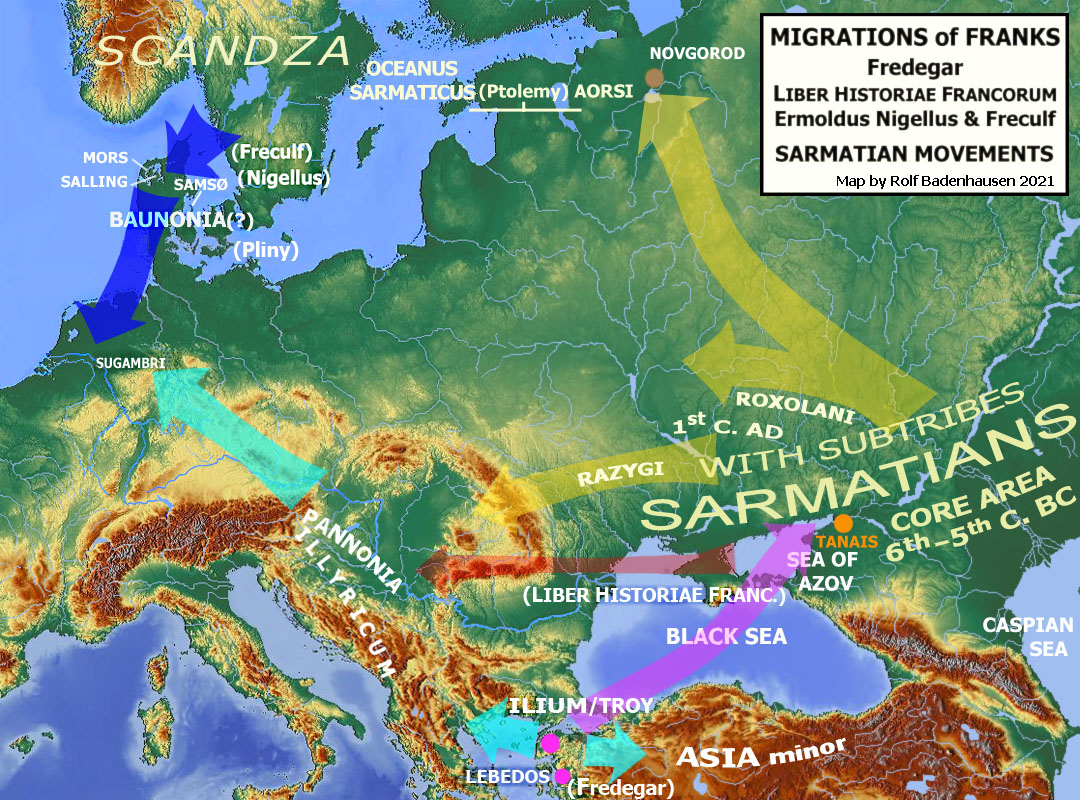

Migration of early

Franks or ‘Salian Franks’.

|

|

Pannonia or Baunonia

?

As quoted above, Gregory of Tours actually maintains

that the Franks migrated from ‘Pannonia’ into their well known later

domain,

which then, since 4th century, was

formed

mainly on the left bank of the Rhine. However,

Reinhard Wenskus does not exclude the possibility that Gregory could

have misunderstood Baunonia

or Bannomanna

as Pannonia. Both name forms of this location provides Pliny

the Elder in his Naturalis Historia;

cf.

Wenskus, Der

‘hunnische’

Siegfried. Fragen eines Historikers an den Germanisten. In:

Heiko

Uecker (Ed.), Studien zum

Altgermanischen, RGA

Ergänzungsband 11 (1994). p. 688. Pliny writes in book

IV,xiii(94), cf. Bostock & Riley IV(,27),13:

|

| |

Exeundum

deinde est, ut extera Europae dicantur, transgressisque

Ripaeos montes litus oceani septentrionalis in laeva, donec perveniatur

Gadis, legendum. insulae complures sine nominibus eo situ traduntur, ex

quibus ante Scythiam quae appellatur Baunonia unam abesse diei cursu,

in quam veris tempore fluctibus electrum eiciatur, Timaeus prodidit;

reliqua litora incerta signata fama.

Transcript

by Julius Sillig, cf.

https://opacplus.bsb-muenchen.de/title/BV008402647/ft/bsb10315371?page=430

|

| |

[Transl.:

Having left the Black Sea for telling about

outer European parts; and after

crossing the Riphean Mountains ‹

Belarusian Ridge? › we follow the

Northern Ocean’s shoreland on the left until we cross Cádiz. On

this route many islands are said to be nameless. Among these, there is

one located off Scythia ‹

that, according to contemporary ethnic and geographic estimation,

extends at least to the Baltic Sea, i.e. Ptolemy’s OCEANUS

SARMATICUS ›

and called Baunonia, where

in springtime

amber is ejected into its floodwaters and which, as Timaeus said, can

be

reached in one day from the mainland. Telling about the remaining

shoreland is uncertain.]

The obvious island Baunonia/Bannomanna,

since Pytheas of Massalia considered with Metuo(nis),

has been

scholarly regarded either in the

North Sea area, west of Jutland, or somewhere in the Baltic Sea, cf. Reallexikon

der germanischen Altertumskunde, RGA 20, pgs 1-4.

Pliny refers to Pytheas and Metuo(nis)

in XXXVII,xi(35–36)

with this description:

|

| |

Pytheas

Guionibus, Germaniae genti, accoli aestuarium oceani Metuonidis nomine

spatio stadiorum sex milium; ab hoc diei navigatione abesse insulam

Abalum; illo per ver fluctibus advehi ‹ scl. electrum › et esse

concreti maris

purgamentum: incolas pro ligno ad ignem uti eo proximisque Teutonis

vendere. huic et Timaeus credidit, sed insulam Basiliam vocavit.

Philemon negavit flammam ab electro reddi.

|

| |

[Transl.: According to

Pytheas, the Guiones ‹ ‘Ingvaeones’ presumably understood

as ‘inGva(e)ones’ ? ›, a

Germanic race, inhabit the ocean’s ‘aestuary’ ‹ surf

zone › named

Mentonomon ‹

Metuonis ›, whose

size is six thousand stadia, and which can be

reached in one day from the island Abalus, where in spring amber is

washed up by the waves just as concrete ejection of the sea; further,

the inhabitants light wood with it, and sell

it to their neighbouring Teutones. Timaeus, too, believes in this, but

called the island Basilia.

Philemon negated the flammability of amber.]

Regarding

the identification of Abalus,

as said

being in proximity to the Teutones, who temporarily settled in a

southern or

southwestern region of the Jutland Peninsula, some analysts think

about Heligoland, whose area is said to have been enormously

larger in the Middle Ages. However, remarkable findings of amber

on this island, which some researcher likes to connect with the seat of

an Eddaic hero Helgi, can

not be denied.

|

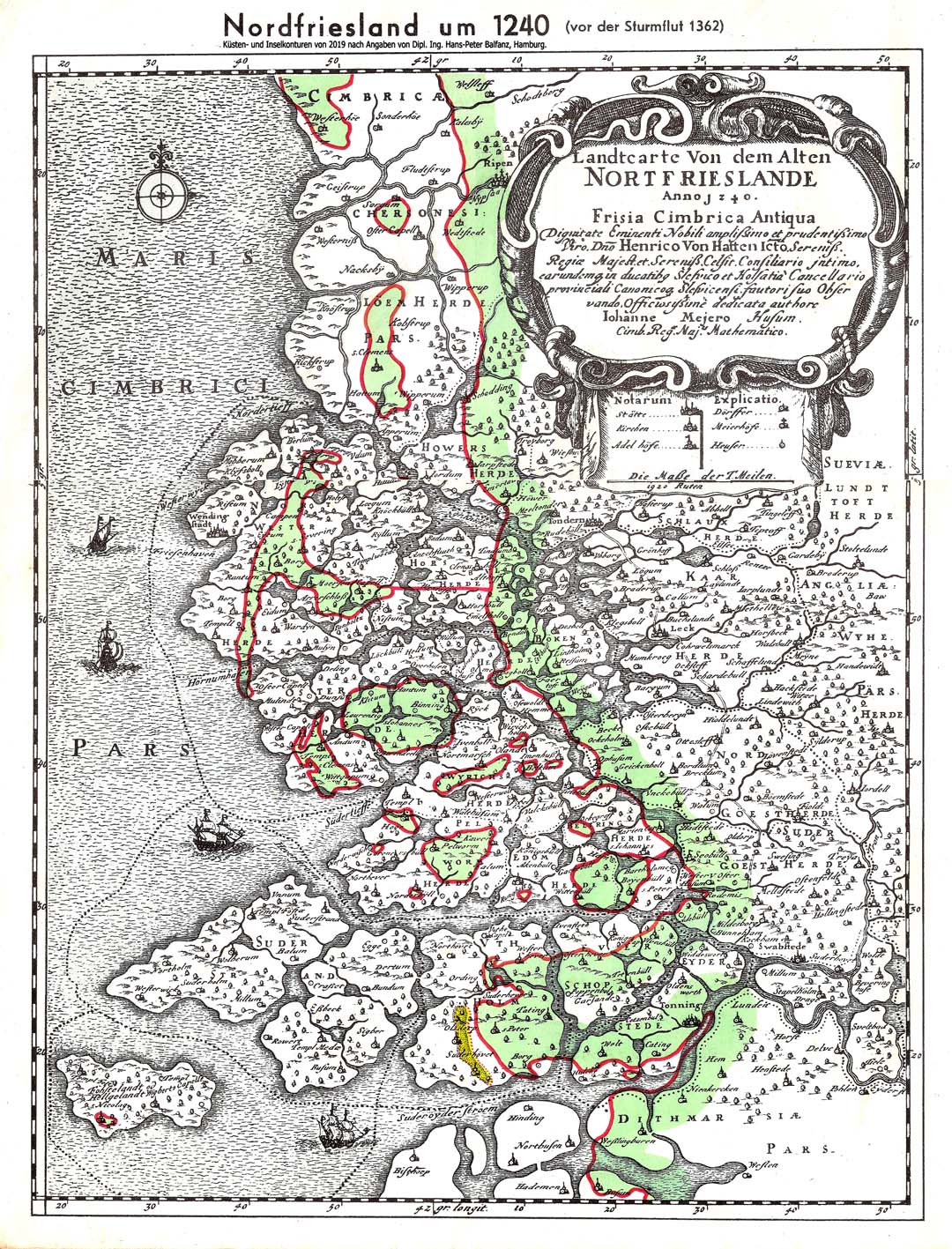

The western part of

Jutland according to the

mathematician and cartographer Johannes Mejer, who

had evaluated so-called ‘Urbare’, certifications of land

ownership, for this geographic survey.

The sinking of enormous land areas of a group of

islands off western Jutland was caused by the

devastating Marcellus floods in the years 1219 and 1362, cf.

Heligoland below left on the map.

The current land outlines (red) were drawn by Dipl. Ing.

Hans Peter Balfanz, Hamburg.

Baunonia has been estimated also west of Jutland. In

its former area are said another 23 islands that were

circumnavigated by the Romans, of which Bŭrcana, as

Pliny further notes, is considered the best known.

Could it have been the eponym for Borkum, which is

possibly too far to the west?

Image resolution for A4 print format: 300 dpi

|

Taking this context further, some elder and modern authors seem to

agree with

the spelling form Basilia(m)

of Pytheas and Timaeus in

the meaning of Balcia(m), as

Pliny quotes the latter

toponym provided by Xenophon of Lampsakus, cf. Pliny IV(95).

However, as regards

the identification of this large island with ‘Baltia’, Josef Svennung

points out that inscriptional evidence of -ci- before a vowel for a

replacement with -ti- can be found in transmissions already since the

2 nd

century: e.g. tercia for tertia. Thus, regarding the

Isle of ‘ a.balus’, its

original root may have been a*Bal.

Referring to some

conjections already by Kaspar Zeuss (1837), Josef

Svennung and Richard

Hennig would even support an equation of this potential Baltia

with the Scandinavian Peninsula – and why could not the Jutland

Peninsula then be

meant inclusively or instead? |

| |

Zeuss, Die

Deutschen und die Nachbarstämme, Munich 1837, Heidelberg

1925, cf. 1837 pgs 269-270.

Hennig, Die

Namen

germanischer Meere und Inseln

in der antiken

Literatur. In: Zeitschrift

für

Ortsnamenforschung 12 (1936), pgs 3–20, cf. p. 11.

Svennung, Scandinavia

in Pliny and

Ptolemy. Kritisch-exegetische Forschungen zu den ältesten

nordischen Sprachdenkmälern (= Skrifter utgivna av Kungl.

Humanistiska Vetenskaps-Samfundet i Uppsala 45). Uppsala 1974;

cf. p. 34f.

PANNONIA

near Illyricum or Illium ?

On the other hand, Pannonia on the Balkan Peninsular has been

geographically connected with the Illyrians/Illyrii

already by the descriptions of Hecataeus of Miletus (6th

century BC), cf. also the Roman province Illyricum of 1st

century.

The chronicle of the so-called Fredegar

makes known the

‘Trojan origin’ of the Franks in his books

II,4–6,8,9 and III,2.

According to Fredegar’s

accounts, which he

recursively defends i.a. with the writings of Jerome of Stridon and

Virgil (III,2), the people of

‘Latium’

under Aneas and those led by Friga were inferred from

Troy. In II,8 Fredegar

calls Frigia/Friga, an eminent

protagonist of the Franks, as brother of Aeneas, whom he introduces as a rex Latinorum. Furthermore

(II,4–5 and III,2), the pseudonymous

authorship

of this chronicle claims Priamus as the

first king of the Trojan Franks, and moreover, that

these people had to emigrate from Troy because of

its

cunning conquest by Odysseus. Then Fredegar

proceeds to evocate

that the

division and the great

wandering of

these Trojans occurred during and after Friga’s rulership: One part

emigrated to

Macedonia and formed it essentially thereafter, and the other, now

under Francio, was guided to settle on the banks of

the Danube and the Ocean ‹

cf. III,2 – which one: the

Atlantic, the North or Black

Sea? ›. The reader of III,2 is also told that the later

Franks under Friga moved through Asian territory,

and II,6 provides also a

further

separation on the Danube, which brought forth the Torci/Turqui. Fredegar then continues that

Francio’s people came to a

region near the

Rhine, where they built an unfinished city according to the model

of Troy.

Regarding in this context the Colonia

Ulpia Traiana

(CUT) at Xanten on the Lower Rhine, Fredegar’s

localization

appears even as an unhistorical northern

allocation. Ewig

follows this

interpretation:

|

| |

Mit der

civitas ad instar Trogiae nominis

ist unzweifelhaft die Colonia Ulpia Traiana gemeint, die

als Ruinenstätte seit dem späten 4. Jahrhundert das Bild

eines opus imperfectum bot

und als Troja in der um 500 von dem

Goten Athanarid

verfassten Beschreibung der Francia Rinensis verzeichnet ist.

|

| |

[Eugen Ewig, Troja und die Franken.

In: Rheinische

Vierteljahrsblätter, 62 (1998), pgs 1–16, see p. 7.]

|

| |

[Transl.: The

civitas ad instar Trogiae

nominis undoubtedly refers to the Colonia Ulpia Traiana, which,

as a

ruined site since the late 4th century, presented the image of an opus imperfectum and is recorded as

Troy in the description of Francia Rinensis written around 500 by the

Goth Athanarid.]

Edward James (The

Franks, p. 235) agrees basically with

this possible

context and argues without Athanarid’s ‘mythical assoziation’:

|

| |

It is

just as likely that the myth was concocted by some erudite Frank,

or Gallo-Roman, around the year 600 ‹

i.e. after Gregory’s death › , to

give the Franks a dignified ancestry, and one that made them the equal

of the Romans.

The Liber

Historiae Francorum

(LHF) provides the

‘Trojan

history of the Franks’ with only an

approximate matching story (c.1–3).

There are mainly these significant

differences:

|

| |

|

According to the Liber,

Greek kings were warring against the tyrant Aeneas, who finally

fled from Illium (Ilium =

Troy) with his loyal people to Italy. However, the rest of the

Trojan people was shipped by two leaders called Priamus and Antenor,

and

these 12,000 people came across the Black Sea via Tanais, (on) Don

river, and the Maeotian marshes (Sea of Azov) to ‘Pannonia

nearby’, where they built a civitas Sicambria

(c.1). After rendering

successfully service for the Romans against Alans in the Maetion

region, they received from ‘Emperor Valentinian’ the name Francos

– the ‘Wild People’

in Attic language as already mentioned by Isidore of Seville, Etymologiae

IX 2,10 and (e.g.) the Carolingian scholar Ermoldus

Nigellus, Carmen in

honorem Ludowici Pii (c.2).

The Liber then narrates that

after ten years, when the Franks violently refused to pay the customary

tax to

the Empire, their leader Priamus was killed in fighting for their

independence. As the Liber's

authorship underlines this

resolute military response of the Romans,

Priamus' Franks finally had to flee to the Rhine

because of their superiority (c.3).

A civitas

called Sicambria was not found in the regions of Pannonia and the

Danube (Ister), but

Tacitus annotates a cohors

Sugambra that repulsed rebelling Thracians (dated AD 26), cf. Annals

IV,47.

The only Sicambrians or

Sugambrians we reliably know of have been historically localized mainly

in the

eastern Westphalian Lowland and, temporarily, on the Lower Rhine. Since

Gregory

connects Clovis' regional descent with the same region, the Franks

under

his predecessor(s) may

have previously settled east of the Lower Rhine. But he nowhere tells

the Trojan legend in his Decem Libri

Historiarum.

This very dubious Trojan legend goes back further in time. Already in

the 5th

century the Gallo-Roman bishop, poet and politician Sidonius

Apollinaris spread the story that the people of Auvergne (Clermont)

were said to be of the same blood as the Trojans. He wrote in his

letter to Bishop Graecus, dated to 474 or 475, on the martial

Visigothic

annexation (Epistolae

VII,7,2):

|

| |

Facta

est servitus nostra pretium securitatis alienae; Arvernorum, pro dolor,

servitus, qui si prisca replicarentur, audebant se quondam fratres

Latio dicere et sanguine ab Iliaco populus computare.

|

| |

|

[MGH Auct. ant. 8 (1887), p. 110.]

|

| |

[Transl.:

Made is our servitude, the price for the safeness of others. The

mental pain of the servitude of the Avernians, so elder venerable

telling, is that they once dared to call themselves Brothers of Latium,

‹ preceding geoethnic term for Rome › and

to reckon themselves to the blood of Illium’s people.]

Sidonius had certainly read De Bello Civili

written by the 1st

century Roman poet Lucanus (‘Lucan’), who left this passage on the wars

between Julius Caesar and Pompey in book

I:

|

| |

|

Arvernique

ausi Latio se fingere fratres sanguine ab Iliaco populi

|

| |

|

[Transl.:

and

Avernians pretending to be Latium’s brothers, as if they were a people

of Trojan blood.]

In

the 4th century, the Roman historian

Ammianus Marcellinus may have quoted the idea of Trojan origin of the

Gauls, see his Res gestae XV,ix,4–5:

|

| |

c.5:

Aiunt

quidam paucos post excidium Troiae fugitantes Graecos ubique dispersos

loca haec occupasse tunc vacua.

c.4: Drasidae memorant re vera fuisse populi partem indigenam, sed

alios

quoque ab insulis extimis confluxisse et tractibus trans rhenanis,

crebritate bellorum et adluvione fervidi maris sedibus suis expulsos.

|

| |

[Transcription: Ammiani Marcellini Rervm gestarvm libri

qvi svpersvnt. In: Wolfgang Seyfarth (Ed.), Bibliotheca scriptorvm Graecorvm et

Romanorvm Tevbneriana. (Leipzig 1978).]

|

| |

[Transl.: c.

5: Some

even claim that after the destruction of Troy, a few, fleeing from the

Greeks, scattered everywhere and took possession of these

uninhabited regions. ‹ as

these were mentioned previously: ›

c. 4: The Druids remember that some of the

people were really indigenous, but that other inhabitants flocked from

the islands on the coast and from the areas beyond the Rhine, having

been expelled from their former abodes by frequent wars and sometimes

by inroads of the stormy sea.]

However,

still to be annotated are the records of the

Roman writer Tacitus as a likely or potential receptive source. As he

provides

in

his Germania, c. 3, ‹

the Trojan hero ›

Odysseus is said to have built Asciburgium

and

an altar there on the banks of the Rhine. (Asciburgium

is the Latin name of the Roman castra at Moers-Asberg on the Lower

Rhine.)

The historical point of establishing the Trojan descent of the Franks

has been

thematized with Ammianus. With him in mind, Ian N. Wood predicates:

|

| |

It is

likely that the Franks, like the Burgundians,‹ ! › received

the epithet ‘Trojan’ within the context of imperial diplomacy. {

Wood,

‘Ethnicity and the ethnogenesis of the Burgundians’ (1990)

pp. 57–8. } This would not

have been

the only occasion on which the notion of

brotherhood was used to imply a special relationship with Rome; the

people of Autun, for instance, regarded themselves as being brothers of

the Romans { Panegyrici Latini, V 2, 4 } as did

the men of the Auvergne.

Subsequently what had been no more than a name implying a certain

diplomatic affiliation between the Franks and Valentinian must have

been interpreted as providing a genuine indication of the origins of

the Franks. The idea will have been elaborated through contact with

what was still known of the Trojan legend.

|

| |

[Wood, The Merovingian Kingdoms

450–751 (1994) pgs 34–35. Footnotes in curly braces.]

|

| |

Wood follows Edward James insofar as

|

| |

in

fact there is no reason to believe that the Franks were involved in

any long-distance migration: archaeology and history suggest that they

originated in the lands immediately to the east of the Rhine.

|

| |

[Op. cit. (1994) p.

35, cf. James, op. cit. pgs 35–38.]

According

to reliable historical sources, the most important

development of the Franks, by which we mean especially their tremendous

rise

by its history of power politics, undoubtedly began in this area. This

rather late view finds support – of course disregarding Fredegar and the Liber – in the earliest extant

mention of

the Franks.

In 291 they first appear as Franci

in a panegyric to the emperors Diocletian and Maximian. About 70 years

later, Aurelius Victor notes in his Liber

de Caesaribus that the

peoples of the Franks (= Francorum gentes) had already

ravaged Gaul by the end of the 250s.

Concluding further about the literary-historical impact of the Troyan

legend, the authors

of Fredegar and the Liber,

possibly

even Sidonius at hand of e.g. Lucan, may have equated the Illyrii

with the people of Ilium/Illium,

the second Latin name of Troy, for creating a precious story about the

progenitors

of the

Franks. According to prevailing scholarly

opinion, it is obvious that Fredegar

and the writer(s)/editor(s)

of the Liber

tried to impute an ancient tribal origin with royal tradition to the

Franks,

which had to be at peers with the highly respected civilizations of the

Romans and the Greeks.

Gregory of Tours vs

Trojan-Carolingian ancestry ?

Gregory of Tours, who might not necessarily mean

that Pannonia as the prominent part of today’s Hungary, could have

suspected all

this; cf. Wenskus (op. cit.), but see Wood (op.

cit. p. 35) remembering Gregory’s devotional relation to St

Martin of Tours coming from there. Though writing definitely before Fredegar

and the Liber’s author(s),

Gregory most

likely reviewed and

rejected foreseeingly the sources and highly questionable

elaborations of these authors and their later editors on the Frankish

Troy myth. At least Gregory refrained from equating the

people of Troy with the Illyrians, whose territory came later under the

Roman Illyricum, which partly overlapped Pannonia or was adjacent to

its region.

With additions known as Continuationes

to Fredegar’s

original transmission of about AD 650, efforts can be observed among

the

(Pre-)Carolingians around Charles Martel’s (half-)brother Childebrand

to corroborate the Trojan reference by

questionably appearing sources of evidence. See, for example, the Historia Daretis Frigii de origine

Francorum, a compilation completed around 770 to present the

origin of the Franks from Dares’ novel Daretis Phrygii de excidio Trojae historia

(likely of the 5th century). This

work is by

no means the

only one with which Carolingian historians imputed knowledge of the

Trojan origin to Frankish history. In the Historia vel gesta Francorum

(apparently completed under Childebrand’s son Nibelung), which was

presented

almost simultaneously with the de

origine

Francorum attributed to Dares, further compilations were cited

in terms of content which had been written as excerpts under the titles

Scarpsum de Cronica

Hieronimi and Scarpsum de

Cronica Gregorii episcopi Toronaci in order to affirm the Trojan

origin of the Franks with further sources. Bede, too,

was used for this purpose: Moreover, the Carolingian author of the Chronicon universale usque ad annum 741

contextualizes the Trojan origin of the Franks at hand of Bede’s

chronology in De temporum ratione,

cf. c.66. The latest Carolingian ethnology of Trojan descent received

further

support from Paulus

Diaconus, who was temporarily active in the scriptorium of Charlemagne.

In his Gesta episcoporum Mettensium,

Paul did not shy away from declaring Ansegisel’s name, who was the

father of Pippin

II, as the ancestral memory of the Trojan Anchises/Anschisus,

as

he could already be

taken from Homer’s Iliad and

Virgil’s Aeneid. Further, the

8th-century author Aethicus ‘Ister’,

whose

epithet may be

attributed to the Danube and/or Istria, knows of details by Frankish

historiography as provided especially by the Liber. Following to certain extent

also the Historia Daretis Frigii de

origine Francorum, he forwards the Trojan Frigia/Frigio as the

father of Franco and Vasso in his rather bizarre Cosmographia.

Localizing Meroveus

Regarding

the Frankish ancestry of the first half of 5th

century, a Germanic chief called Meroveus,

the

suggested grandfather of Clovis I, appears

recorded for rendering heroic service

to the Romans about 417. At that time, possibly as a merited

high-ranked

mercenary, this Meroveus

(Merovech) appears

rewarded with the leadership of parts of the Germania

inferior and Belgica inferior,

nowadays pertaining to

Dutch, Belgian and German territory. He could have ruled even

Sicambrian

and/or adjacent regions east of the Lower Rhine, albeit we do not know

where he came from. We may also question whether his

father

was the leader of those Franks who moved eastward to and possibly

across the Rhine in the second half of the 4th

century.

Furthermore, we know that a few generations earlier a Merogaisus

is said to have commanded Bructerians, temporarily located on the

eastern bank of the Lower Rhine along the Lippe river, who were

defeated and subjugated by Constantine the Great in 306. This may give

rise to the etymologically- ethnically- geographically based conjecture

that Merovech could also have

had a rulership in this area in the first half of 5th

century. We may also annotate that Flavius Merobaudes,

a native Frank († 383

or 388), was acting under Emperor Valentinian II

as magister

militum, acting in 377 as consul

for the Western Empire.

With regard to geoethnic identifications, Karl Müllenhoff (Zeitschrift

für deutsches

Altertum, 6, p. 433) follows Heinrich Leo (Lehrbuch

der Universalgeschichte 2, 28) who connects Merovingian

location

with the Dutch watercourse Merwe

(Merwede). Franz Joseph Mone

(Untersuchungen zur

Geschichte der teuschen

Heldensage,

1836, p. 47) recounts some authors who have already combined

likewise.

Emil Rückert (Oberon

von Mons und die Pipine

von Nivella, 1836, p. 39) argues

accordingly:

|

| |

Das

herrschende Geschlecht der Franken wohnte an der

Merwe oder Merowe, d. h. der unterhalb Löwenstein mit der Maas

vereinigten Waal und hiervon empfing es den Namen Merowinger,

Morowinger, welchen auch ein König aus diesem Hause, Meroväus

oder Moroväus,

Merwig, trug. Der Mervengau ist jenes Maurungania ad Albim (wohl

Vahalim), welches

der Geograph von Ravenna als früheren Aufenthalt der prima linea

Francorum angibt.

|

| |

[Transl.: The

ruling Frankish dynasty was dwelling on

the Merwe or Merowe ‹ today

the Dutch Merwede ›,

where the Meuse meets the Waal

below Lionstone

Castle ‹ the

Lovensteyn or Loevestein ›;

and the Merovings or Morovingians received their name from that former

watercourse,

and also one of their kings, Meroveus, Moroveus, or Mervig, was named

likewise.

This district called ‘Mervengau’ is that ‘Maurungania ad Albim’ ‹ obviously

the ‘Vahalim’ - cf. Vahal, Waal › which

the Geographer ‹

‘Cosmographer’ ›

of

Ravenna

notes as the early location of

the ‘prima linea Francorum’.]

Eugen Ewig regards the earliest

region of the Salian Franks originated in the region of the Overyssel.

This river is crossing the

former Sal-land

which may stand for the

former central part of the Frankish Salia,

as roughly marked today by the Dutch towns Deventer, Kampen and the

German Nordhorn. Likely with Batavian people, they afterwards

migrated to Toxandria which

encompassed the current Dutch province of North Brabant and, finally in

the first half of the 5th century,

the region

mainly west

of the woodland called Silva

Carbonaria.

According to estimations mainly based on archaeological

explorations of Frisian and Low Saxon lands, the Salian Franks were

settling previously, until c. 365/370, between Mid and North German

lands up to the

middle course of Weser river; cf. for instance

Eugen Ewig, Die

Merowinger und das Frankenreich, p. 9. Following further

archaeological and historical estimation, Saxon

tribes had forced them to move south- and southwestward in the second

half

of the 4th century. Thereafter, after

the

beginning of the 5th century, the

Franks

withdrew

to regions mainly on the left side of the Lower Rhine.

The Cosmographer of Ravenna describes the geography of the Francia

Rinensis between c. 480 and 490. He reckons the Germania

inferior,

almost the whole Belgica superior

(presumably without Verdun) and a

northern part of the Germania

superior to the ‘Rhenish Franks’, cf. RGA 9 (1995) p. 369.

|

Lovensteyn

of 1630, painted by C.J.Visscher.

The

castle was (re-?)built

between 1357 and 1368 by Lord Diederick van Horne who was (nick-)named

Loef (Lion). In 1385, Albrecht van Beieren took over possession of the

castle

and appointed his trustee Brunstijn van Herwijnen as the castle’s

keeper.

|

|

|

This

colourized old photo of Loevestein Castle was made on the eastern bank

of the Waal, approximately 2 miles (3 km) from the Merwede’s mouth.

|

|

|

Fredegar’s

Merovingian parable based on

northern

background (?)

It seems obvious

that already in and after the 3rd century AD

the

Franks settled Frisian coastland extending from the banks of the North

Sea to the Channel. Regarding this spatio-temporal situation, Ian N.

Wood combines the demonic origin

for the Merovingians – its

lineage gendered by a bistea Quinotaurus (Fredegar’s book III,9, see

below under Merovingian etymology and

(re)placements)

– with a suggestive

association of them with the sea:

|

| |

This

association can, in fact, be paralleled by

references to Frankish maritime and piratical raids against the Channel

coasts and on the lower Rhine in third-, fourth-, and fifth-century

sources.29 It is also apparent in the

poems

of Sidonius

Apollinaris, who sees the Franks as providing the touchstone for

swimming skills.30 In large measure,

before

the fifth

century, the Franks appear as a maritime people, collaborating with,

and often scarcely differentiated from the Saxons.31

__________________

29 Ian N. Wood,

The Channel

from the 4th to the 7th Cs AD,

in: Maritime Celts, Frisians and Saxons, ed. by Seán

McGrail (1990), pp. 93–97.

30 Sidonius

Apollinaris, Epistulae et carminae, ed. by

André Loyen, 3 vols (Paris, 1960–70), carm. VII.236.

31 Wood, ‘The

Channel from the 4th to the 7th Centuries’, pp. 94,

96.

|

| |

|

[Wood, Defining

the Franks:

Frankisch origins in early medieval historiography.

In: From Roman Provinces to

Medieval Kingdoms, ed. Thomas F.X. Noble

(2006), pgs 91-98, cf. p. 93.]

Not basically

contradictory to this abstracted focus on the

genesis and localization of the Merovingians, we can encounter

an obvious early ‘Nordic representative’ of them: turning to the heroic

lays of the Edda and the Vǫlsunga

saga, their writers know of a king called

Hjalprek. Some analysts suggested

him as Chilperic I, but he could have been

confused with Childeric I, father of Clovis I

(likely the Old Norse Hlǫðvér

mentioned in the Wǫlundarkviða

and Guðrúnarkviða

II), which may

indicate an early tradition conveyed already in the time of that

Chilperic I. In the

Guðrúnarkviða II,25, Gudrun’s

mother

offers (a part of) Hlǫðvér’s

sali = Clovis' kingdom to the brave one who avenges the death of

her son-in-law Sigurð.

Clovis' alleged father Childeric is said to have sailed as far as

the Mediterranean, to have had also martial Anglo-Saxon activities and,

if representing Hjalprek,

also a realm in Denmark or rather on the Jutland Peninsular. Further,

a Saxon chief Cheldric appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia

Regum Britanniae. Since the Thidrekssaga may

point to an analogous or similar dynastical-geographical milieu that

already show the Sinfiǫtlalok and Sigurðarkviða

Fafnisbana ǫnnur, we may also recognize the

figures

called Nidung and Ortvangis, and regions to be

determined as the Hesbaye (not ‘Hispania’) in Salerni

(geostrategically the Salian province Belgica II) and Þióð/Thiodi/T(h)y

on Jutland.

Regarding the latter region, the lands around the Limfjord on

the ancient ‘Amber Route’, of considerable strategic

importance for maritime Frisians, Franks and Saxons,

seems worth the effort to scrutinize there the

presence of the first Meroveus.

There are at least two

locations of

interest whose former spelling and tradition

seem to indicate themselves as name spending godfather: The isle of Mors

with known word forms of ‘Morø...’ and, close to the east, Cap Salling.

Further to mention is Samsø

(Samsey) north of Funen, where the Lokasenna,24

from the Poetic Edda already narrates a meeting of Loki

with Odin. The naming of Samsø,

a venue given by the historiographer Saxo Grammaticus and Old Norse

sagas, is said to be

based on ‘Sams ey’ (‘Sam’s Isle’) and may appear as personalized as the

name Samson in the

Merovingian genealogy. Appearing rather as a Salian-Frankish than

Italian hero of the Thidrekssaga, Samson

as the nickname or second name of Childerich – or the Old Norse Hjalprek – has been critically

questioned in the bandwidth between saga and historiography:

|

| |

|

Rolf

Badenhausen, Zur

Historizität der Thidrekssaga: Teil I: Frühmerowingische

Herrscher und „Samson“. In: Der

Berner 80 (2020), pgs 24–38;

Idem, Gallo-Roman Warlords:

›Samson‹ – Childerich

– Odoaker. In: Der Berner 87

(2021), pgs 29–53.

|

|

An

excerpt from the Ortelius Map of Jutland by M. Jordano.

We may wonder if

Freculf could connect the tip of Jutland with a Scandinavian

environment.

Otherwise, these locations could have been the temporary seat of the

migrating Merovingian eponym of the Franks.

|

|

With respect to Fredegar’s

parable of

Merovingian genesis, possibly typified by

means of rather a native Nordic chief Meroveus

with (e.g.) ‹ impressing horns on his

furry

alien helmet ›, we

may wonder about Emil

Rückert’s

successive order of Merovingian onomastics and question furthermore:

Was there already any recurrently related Nordic homeland of the

invading

‘Salian’ or Merovingian

founder, the name spending godfather of that dynasty

which the Dutch Merwede and

its contemporarily surrounding

region Salland or, more

common, Salia seem to

remember?

Reinhard Wenskus remarks that Bishop Freculf of Lisieux,

formerly a pupil at

the scriptorium of Charlemagne’s Aachen residence, claims Scandinavian

origin of the Franks despite of his knowledge of the Trojan legend, cf.

J.

P. Migne, Patrologiae cursus completus, Seria I, latina, CVI, col.

967:

|

| |

Francos ...

de Scanza insula ... exordium habuisse; de qua Gothi et ceterae

nationes Theotiscae exierunt, quod et idioma lingua eorum testantur.

|

| |

[Quoted by Reinhard

Wenskus, Sachsen

– Angelsachsen –

Thüringer. In: Walther Lammers (Ed.), Entstehung und

Verfassung des Sachsenstammes,

Darmstadt 1967, see pgs 514–515.]

The RGA

(see

appendix below) recounts that Feculf’s contemporary Ermoldus Nigellus,

a son of Louis the Pious,

notes in the vita of his father a fama

(heroic lore,

popular tradition) that

situates the origin of

the Franks to the neighbourhood of the Danes.

After all, it seems superfluous to underline that both

Carolingian scholars have deliberately ignored the southern Pannonian

migration of the Franks provided by Fredegar,

the Liber

Historiae Francorum

and – if actually referring to the southern Pannonia – Gregory of

Tours.

A subtle figural-personified reference to

Frigio’s Franks migrating rather via Frisian islands may have been left

by the first continuator of the Fredegar’s

chronicle in ch. 17, where these people appear paraphrased with forms

such as maritimam

Frigionum/Frigione..., Insulas Frigionum..., exercitum Frigionum...;

cf. MGH

SS rer. Merov. 2

(1888), p. 176.

Merovingian etymology and

(re)placements

A further onomastic approach, which

basically does not contradict these northern localizations of

apparently experienced Merovingian seafarers, might come from the

students

and translators of the Old English Beowulf,

cf. its lines 2920–2921:

|

| |

|

...

ús

wæs á syððan

merewíoingas

milts

ungyfeðe.

Karl Simrock equated

the term on the left with the ‘Merovingas’ (Ger.

‘Merowinge(r)’,

cf. Beowulf,

Stuttgart & Augsburg

1859, p. 147). Francis B. Gummere correspondingly translated

this very passage

|

| |

|

And ever since

the Merovings' favor

has failed us wholly...,

|

|

whereas other reputable

philologists (e.g. Levin Ludwig Schücking, Martin Lehnert,

Gisbert Haefs) have emended the term in

question to the compound

|

| |

|

mere-wícingas =

sea-pirates.

Fredegar

provides this parable of the Merovingian

genesis ( book III,9),

as already quoted in the author’s

article Merovingians

by the Svava:

|

| |

|

|

Fertur, super

litore

maris aestatis tempore Chlodeo cum uxore resedens, meridiae uxor ad

mare labandum vadens,*

bistea Neptuni Quinotauri similis eam adpetisset.

Cumque in continuo aut a bistea aut a viro fuisset concepta, peperit

filium nomen Meroveum, per co regis Francorum post vocantur Merohingii.

[It is said that in

the summertime Chlodio sat with his wife on the shore of the churning

sea, and at noon she went to ‹

take a bath

in › the Labadian Sea*

where a beast of Neptune,

which resembled a Quinotaur, took possession of her. Whether

he may

have been begotten by the beast or by the man, in any case, she bore a

son named

Meroveus, and after him the kings of the Franks were later called

Merovingians.]

_______________

* Fredegar

most

likely means Labadus or

Lebedus

(Lebedos), one of the twelve cities of the Ionian League located on the

Aegean Sea as the

urbs Ioniæ

in

Asia

minori, maritima in parte Australi Isthmi

peninsulæ Ioniæ;

quæ etiam Labadus

dicta est...

as explained by the author of the Annales

Veteris et Novi Testamenti..., Jacobi Usserii Annales, Genevæ

MDCCXXII, Index

Geographicus ‘L’.

Image by

www.figuren-shop.de with added details by the author.

|

|

Does this ‘Greek

version’ allow to re-transfer this location, just c.

135 mi. (c. 218 km) south of the archaeological Troy, to a shore

of

Chlodio’s domain somewhere on the North Sea? And we further may ask for

a

compromise to all translators mentioned above: Is there

generally reason enough to contradict the

derivative-based identification mere-wícingas

→

Merovings?

According to all this we can only assume with this abstract that

Chlodio’s Franks could have come from the south to the northern Rhine,

while his successor

Merovech possibly had his roots rather in the north. Thus, it seems

obvious that Fredegar did not

arbitrarily decide for the drastically

depicted interference of Merovech into the ancestral lineage of

Chlodio’s

Franks. Considering at least contemporary tradition, understanding and

conviction, this may actually correspond with a massive

intervention into the ethnic identity of the gens Francorum: If Chlodio’s wife

had been impregnated by a barbarian individual, the male Trojan

lineage would have been lost. Fredegar

looks upon this highly probable disruption as an authoritative offence

against the prima linea Francorum,

and he showed reason enough to

vent his frustration about this with a splendid theatrical performance.

Because he hardly wanted to see the Trojan lineage broken, he

transferred the stage of his drama, in which Chlodio seems to appear in

the

rôle of a ‘vice-father’, to that impressing coastal scenery

which had to be not far away from Troy.

Gregory’s vague statement on Merovech’s racial inclusion, ascribing him

to Chlodio’s stock ‘as asserted’ : De

huius stirpe quidam

Merovechum regem fuisse adserunt (op. cit. II,9),

has

been much thematized. With regard to Fredegar’s

parable, however, we

can obviously conclude

no more than an unclear consanguinity between Merovech and Chlodio.

However, we can also ask urgently: would Fredegar have written his play

at all if Childeric had been

fathered by Chlodio?

|

Appendix

The RGA vol.

22 (2003)

pgs

189–191, see translation

below, states on the ‘Origo

gentis’ of the Franks:

|

| |

§

4. Franken. a.

Herkunft

des

Volkes, Tradition des

Volksnamens, Kg.smythos. Einige für

die Genese des frk.

Kgt.s und

der frk. gens wesentliche

Qu.zeugnisse enthalten implizite

Herkunftstraditionen. Gewisse Elemente in der Tradition scheinen

auf ö. und n. Züge bei merow. Kgt. (→ Merowinger) und

Volksbildung hinzudeuten. Bisweilen begegnet eine Identifizierung

des merow. Geschlechts mit den bei → Ptolemaeus (48, II, 11,11)

erwähnten Marvingi. Diese sind zu den bei dem → Geographen von

Ravenna (I, 11) genannten Maurungani (→ Mauringa/Maurungani)

gestellt worden, die dort einerseits zu Elbe und Franken in Bezug

gesetzt sind, andererseits Grenznachbarn der beiden Pannonien (IV, 19)

sein können (81, 26–28. 72; 171, 527). Einige Namen lassen

später (58, I, 9; 5, 31; 7, 2502. 2914. 2912) Angehörige des

Kg.sgeschlechts (→ Chlodwig , → Theuderich I.) bzw. die Franken

schlechthin als Hugonen und damit in Verbindung mit den → Chauken

erscheinen (171, 527 f.; 170, 190. 196). Hatte schon Claudian ([XXI,

222. 226]; X, 279) die Sugambrer mit dem Rhein bzw. der Elbe

zusammengebracht, so führt Ermoldus Nigellus (Vita Ludwigs des

Frommen IV, 13–18) eine fama an,

nach der die Franken aus der

Nachbarschaft der → Dänen stammten, und kennt Frechulf von Lisieux

neben der Herleitung der Franken aus Troja ihre Herkunft aus

Skand. (PL 106, 967C/D). – Im Fall der Sigambrer/Sugambrer ist zu

beachten, daß die zeitlich frühesten Belege

(Claudian XXIV, 18; XXVI, 419; XV, 373; XVIII, 383; Apoll. Sidon.,

Ep. IV, 1,4; VIII, 9,5, 28; Carm. VII, 42. 114; XIII, 31; XXIII, 246)

sich auf die Franken insgesamt, die späteren, → Venantius

Fortunatus (Carm. VI, 2,97) und → Gregor von Tours (21, I, 31), sich

mit Charibert und Chlodwig auf Angehörige der merow. Dynastie

beziehen. Offenbar werden hier Interdependenzen zw. frk. Volk und

Kgt. faßbar, die über die faktische Dimension

hinausführen.

Herkunft von der See und Verbindung mit den

Sugambrern

gehören in

den Zusammenhang der Herkunft des Volkes. Außer in den

vorgestellten Reflektierungen ist das Thema mit verschiedenen

faktischen und mythischen Komponenten in einer Wanderungssage

ausgeführt, die bei Gregor (21, II, 9) zuerst, dann bei → Fredegar

und im → Liber historiae Francorum in charakteristischen

Ausgestaltungen in der Trojasage, faßbar ist. Assoziationen, die

auf eine Verbindung der Sigambrer mit der frk. Ethnogenese

verweisen, begegnen zuerst bei dem Byzantiner Johannes Lydus (um 560).

Er berichtet, die

Sigambroi würden von den Gall.

an Rhein und

Rhône nach einem hegemon

Phraggoi genannt (De mag. III, 56; I,

50). Zur gleichen Zeit erfolgen die Sigamber-Apostrophierungen

merow. Herrscher. Möglicherweise handelt es sich um die

Übertragung gentiler, auf die Franken insgesamt bezogener

Elemente. Indem Venantius Fortunatus den Kg. als

progenitus de clare gente Sigamber

apostrophiert und Gregor den

Sigambrerbezug bei

Chlodwigs Taufe in vergleichbarem Kontext verwertet sein

läßt, werden die für das Kgt. wichtigen ideologischen

Komponenten deutlich (62, 14 f. 27).

Gens Sigambrorum begegnet

häufig in der frk. Historiographie

des 7. Jh.s, bes. in bezug zum

hohen Adel. Später erscheint Sigambria als wichtige Station

der frk. Wanderung im Trojazyklus, im Liber hist. Franc. in Pann., bei

Aethicus Ister in Germania lokalisiert.

Isidor von Sevilla (26, IX, 2,101) führt zwei

geläufige, alternative Erklärungen des Namens ,Franken’ an:

die Benennung

a quodam duce eorum und die nach

feritas morum. Ein versifizierter

kosmographischer Traktat, wohl spätes 7. Jh., präzisiert

Isidor mit dem Namen

Franco (MGH Poet. Lat. 4, 2, 554).

Gregor nennt in einer als breit gestreut

gekennzeichneten Version (21, II, 9:

Tradunt ... multi) als Stadien der

Wanderung Pann. – Rhein

– Thoringa. Im Blick auf eine mögliche Verbindung der Franken mit

der See und einer Herkunft des Traditionskerns der → Salier von

der Nordsee ist gefragt worden, ob Gregor nicht das bei → Plinius

(44, IV,94) begegnende Nordsee-Küstengebiet Baunonia (→ Burcana)

in Pann. umbenannt habe (189, 4). Mit Blick auf die

Hugen/Hugonen-Tradition ist als Erklärung vorgeschlagen worden,

Gregor könne die mit Pann. assoziierten → Hunnen zu Hugen

mißverstanden haben (160). Diese Erklärungen können

für die Real-gesch. kein überzeugendes Resultat liefern. Doch

steht die Bedeutung von Pann. für die Herkunftssage außer

Frage. Im Liber hist. Franc. (32, c. 1) ist Pann. wichtige Station der

Franken, lange bewohnter Siedlungsraum und neues Ausgangsland (62,

24 f. 12 f. 27–30). Sein Stellenwert als ‚Erinnerungsort’ der

Franken wird dadurch unterstrichen, daß das Kgt. neben der

monopolisierten Sigambrertradition auch das Pann.-motiv für

sich reklamiert. Ein Brief Kg. Theudeberts I. kann wohl in diesem Sinn

interpretiert werden (Epp. Austr. 20: MGH EE 3, 132 f.; 62, 27 f.).

Z.T. weiter zurückreichende Zeugnisse (Avitus

von Vienne, Remigius

von Reims, Aurelianus von Arles) überliefern mit

felicitas und

stimma sidereum der

stirps genuine Momente des merow.

Kg.smythos. Zu

nautischer Praxis und Tradition der Franken wie auch zu ihrem

Kg.smythos gehört die Herleitung der Merowinger von einer

bistea

Neptuni Quinotauri similis. Fredegar

(17, III, 9) referiert die

von

Gregor (21, II, 9. 10) anscheinend unterdrückte Version mit

christl. motivierter Abwehr und macht in Kontamination mit dem

mythischen Ahnen Mero irrigerweise die hist. Figur → Merowechs zum

→ Heros eponymos der Dynastie. Die archaische Verknüpfung von

Götter- und Kg.sreihen scheint hier wider, vielleicht

vermittelt durch eines jener aus → Tacitus (53, c. 2) erschlossenen

carmina antiqua (112, 31). In

weitreichender Deutung

ist die Stelle in ein Syndrom mythol. und hist. Bezüge (Neptun;

Minotaurus) gefügt worden (170, 182–204. 240;

Korrekturen, doch übersteigerte Gegenkonstruktion: 134).

Als für die frk. Ethnogenese und die

Herkunftssage relevante

Momente, die unabhängig vom Trojamotiv erscheinen, sind zu nennen:

Sigambrer, Wanderung, Pann., Rhein, Namensherleitung von einem → dux

(Franco) oder von

feritas morum. (Zu hypothetische

Verknüpfung: 153, 169–173). Man könnte erwägen, ob nicht

die Reminizenz an eine unter Ks. → Tiberius an der unteren Donau

stationierte

cohors Sugambra (Tac. ann. IV,47)

die Verknüpfung

Sigambrer – Franken – Pann. vermittelt hat.

(...)

[Transl.: § 4.

Franks. a. Origin of the people, tradition of the people’s name,

kingship’s myth. Some

of the

essential sources

about the genesis of the Frankish kingship

and the gens contain implicit

traditions of origin. Certain

elements

in the tradition seem to indicate eastern and northern features of the

Merovingian kingship (→ Merowinger) [Merovings/Merovingians]

and the ethnic formation into a national identity.

See → Ptolemaeus [Ptolemy]

(48, II, 11,11) for an occasional

identification of the Merovingian gens

with the Marvingi. They

have

been collocated with the Maurungani (→ Mauringa/ Maurungani) provided

by

the Cosmographer of Ravenna, who reckons and situates them to the

Franks on

Elbe river on the one hand (IV, 19). On the other, the former could

have been

bordering neighbours of the two Pannonias (81, 26–28, 72; 171, 527).

Some names appear later (58, I, 9; 5, 31; 7, 2502. 2914. 2912) as

descendants of the royal ancestry (→ Clodwig [Clovis], →

Theuderich I. [Theuderic I]),

or

the Franks as Hugonen (‘Hugas’)

per se,

and in so far in connection with the →

Chauken [Chauci] (171, 527f.,

170, 190. 196). Since Claudian had

already situated the Sicambrians on the Rhine or the Elbe

([XXI, 222. 226]; X, 279), Ermoldus Nigellus

(Vita of Louis the Pious IV, 13–18) introduced a fama claiming

that the Franks originally came from the neighbourhood of the →

Dänen [Danes], and

Freculf of

Lisieux knows of their origin from Scandinavia besides their

derivation from Troy (PL 106, 967C/D). – As regards the

Sicambrians/Sugambrians, it should be noted that the attested sources

(Claudian XXIV, 18; XXVI, 419; XV, 373; XVIII, 383; Apoll. Sidon., Ep.

IV, 1,4; VIII, 9,5, 28; Carm. VII, 42. 114; XIII, 31; XXIII, 246)

refer to the Franks as a whole, while the later accounts by →

Venantius Fortunatus (Carm. VI, 2,97) and → Gregor von Tours [Gregory

of Tours] (21, I, 31) refer to the Merovingian dynasty with

Charibert and

Clovis. Interdependencies between the Frankish people and kingship,

which go beyond the factual dimension, now appear evident.

The origin from the sea and the

connection

with the Sigambrians belong to the context of ethnic origin. Except

in the above-mentioned reflections, the subject matter is carried out

with various factual and mythical components in a migration legend

which is cognizable at first at Gregory (21, II, 9), then at →

Fredegar and the → Liber historiae Francorum in characteristic

configurations of the Trojan legend. The earliest associations which

point to a connection between the Sigambrians and Frankish ethnogenesis

can be found at the Byzantine scribe John Lydus (c. 560). He

reports that the people of Gaul on the Rhine and Rhône had named

the Sigambroi after a hegemon Phraggoi (De mag. III,

56; I, 50). At the same time the Merovingian rulers received the

Sigambrian

apostrophies. This could be the transfer of gentile elements being

related to the Franks as a whole. Since Venantius Fortunatus

apostrophizes the king as a progenitus

de clare gente Sigamber

and Gregory has left the use of the Sigambrian reference in a

comparable

context at the baptism of Clovis, the important ideological components

for kingship become clear (62, 14f. 27). Gens Sigambrorum meets

frequently the Frankish historiography of 7th

century, esp. regarding high nobility. Sigambria appears later as an

important stage of

Frankish migration in the Trojan cycle, as being located in Pannonia in

the Liber historiae Francorum, in Germania by Aethicus Ister.

Isidore of Seville (26, IX, 2,101)

offers two common and alternative explanations onto the naming of the

‘Franks’: the designations a quodam

duce eorum and feritas

morum. A

versified cosmographic treatise, probably of late 7th

century, specifies Isidore’s version with the name Franco (MGH

Poet. Lat. 4, 2, 554).

In a broadly characterized version

Gregory recounts the stages of migration with Pannonia – Rhine –

Thoringa (21, II, 9: Tradunt ...

multi). In view of a possible

connection of the Franks with the sea and an origin of the traditional

core of the → Salier [Salians]

from the North Sea, it has been

queried

whether Gregory had renamed the North Sea coastal area Baunonia (→

Burcana; see → Plinius [44, IV,94]) as Pannonia (189, 4). With regard

to the Hugen/Hugonen tradition, there is proposed explanation

that Gregory could have misunderstood the Huns, associated with

Pannonia, as Hugen (160). Although this kind of explanation can not

provide a

convincing solution for real history, the significance of Pannonia for

the origin is beyond question. In the Liber historiae Francorum (32, c.

1) Pannonia is an important stage of the Franks, a long inhabited

settlement area and a new starting country (62, 24f. 12f. 27–30). Its

importance as a ‘place of remembrance’ of the Franks is underlined by

the fact that the kingship, besides the monopolized Sigambrian

tradition, also claims the Pannonian motive for itself. A letter of

Theudebert I may be interpreted in this sense (Epp. Aust. 20: MGH EE 3,

132f.; 62, 27f.).

Some testimonies, partially far-reaching

(cf. Avitus of Vienne, Remigius of Reims, Aurelianus of Arles)

provide with felicitas and stimma sidereum of the stirps

genuine moments of the Merovingian kingship’s myth. The derivation of

the Merovingians from a bistea

Neptuni Quinotauri similes

belongs to the

nautical practice and tradition of the Franks as well as to their

kingship’s myth. Fredegar (17, III, 9) refers to the version seemingly

suppressed by Gregory (21, II, 9. 10) with a Christian motivated

defense and, in contamination with the mythical ancestor Mero, he

erroneously makes the historical figure of → Merowech [Merovech]

the →

Heros eponymos of the dynasty. Here appears the archaic link between

the series of gods and kings, perhaps imparted from one of the carmina

antiqua (112, 31) receptively encountered at → Tacitus (53,

c.2).

In a broad interpretation, this site of tradition was embedded into a

syndrome of mythological and historical references (Neptune;

Minotaurus) (170,

182–204. 240; corrections but exceeding counterconstruction: 134).

The relevant characteristic moments –

which are not depending on the Trojan Legend – of the ethnogenesis of

the Franks and their origin appear as: Sicambrians, migration,

Pannonia, Rhine, name deriving from a → dux (Franco) or feritas

morum. (For hypothetical connection: 153, 169–173). One might

contemplate whether the reminiscence of the cohors Sugambra

(Tac. Ann. IV,47), stationed under emperor → Tiberius on the Lower

Danube, could have imparted the chain Sicambrians – Franks –

Pannonia(ns).

(...) ]

Sources

(17) Fredegar,

Chronicarum libri IV cum

continuationibus, hrsg. von B.

Krusch, MGH SS rer. Mer. 2, 1888, Nachdr. 1984, 1–193; oder: hrsg. von

A. Kusternig, Ausgewählte Qu. zur dt. Gesch. des MAs (Frhr. vom

Stein Gedächtnisausg. 4a), 21994, 3–271.

(21) Gregor von Tours, Decem Libri Historiarum, hrsg. von B. Krusch, W.

Levinson, MGH SS rer. Mer. 1, 1, 21951,

Nachdr. 1992; oder hrsg. von R. Buchner, Ausgewählte Qu. zur dt.

Gesch. des MAs 2 und 3, 1959.

(26) Isodor von Sevilla, Etymologiarum sive originum libri XX, hrsg.

von W. M. Lindsay 1–2,

1911.

(32) Liber hist. Franc., hrsg. von B.Krusch, MGH SS rer. Mer. 2, 1988,

Nachdr. 1984,

238–328.

(44) Plinius der Ältere, Historia naturalis libri XXXVII, hrsg.

von H. Rackham, 9 Bde.,

1949–1952, oder; hrsg. von G. Winkler, R. König, 1988.

(48) Ptol., Geographia, hrsg. von C. Müller, 1883, oder: hrsg. von

C. F. A. Nobbe,

1843–45, Nachdr. 1966.

(53) Tac. Germ., hrsg. von M. Winterbottom, 1975.

(62) H.H. Anton, Troja-Herkunft, o.g. und frühe

Verfaßtheit der Franken in der gall.-frk. Tradition des 5. bis

8. Jh.s, MIÖGF 108, 2000, 1–30.

(81) W. J. de Boone, De Franken, 1954.

(112) K. Hauck, Carmina antiqua. Abstammungsglaube und

Stammesbewußtsein, Zeitschr. für bayer. Landesgesch. 27,

1964, 1–33.

(134) A. C. Murray, Post vocantur Merohingii: Fredegar, Merovech

and ‘Sacral Kingship’, in: After Rome’s Fall (Festschr. W. Goffart),

1998, 121–152.

(153) G. Schnürer, Die Verf. der sog. Fredegar-Chronik, 1900.

(160) N. Wagner, Zur Herkunft der Franken aus Pann., Frühma. Stud.

11, 1977, 218–228.

(170) R. Wenskus, Relig. abâtardie. Materialien zum Synkretismus

in der vorchristl. polit. Theol. der Franken, in: Iconologia sacra

(Festschr. K. Hauck), 1994, 179–248.

(171) Wenskus, Stammesbildung.

(189) E. Zöllner, Gesch. der Franken bis zur Mitte des 6. Jh.s,

1970.

|

|

|