The Nibelungen Saga:

The True Core by the Svava?

by

Rolf Badenhausen

[ Deutsche

Fassung ]

|

|

|

Hardcover Edition, 2005

|

|

301 pages [ISBN

978-3-86582-044-1]

|

|

€ 19,90

|

|

bsaw.de

|

|

[Shipping only within Germany.]

|

Hardcover Edition, 2007

|

|

574 pages [ISBN 978-3-86582-589-6]

|

|

€ 24,90

|

|

bsaw.de

|

|

[Shipping only within Germany.]

|

|

This

saga is one of the greatest sagas which have been written in

German language...

Here you can

hear

about those

occurrences by narration of German men, even by a lot born in Soest

where

those actions took place, who have seen unbroken the places where those

occurrences happened, where Hǫgni (→Hagen) fell and Irung was slain,

and the

Snake

Tower wherein Gunnar (→Gunther) had to face his death, and the garden

that is

still

called Niblungs Garden. And all’s standing in the same place as in

former

times when the Nibelungen were slain; even the gates: the eastern gate

where the battle began at first, and the western gate called Hǫgni’s

Gate

which the Nibelungen broke down into the garden; all that is called

similarly

as it happened formerly. Even those men told us about it who were born

in Bremen and Münster Castle. They did not know of each other for

sure, but all of them told about it in the same way. Most of it does

even

correspond with old German ballads by wise men who rhymed about the big

events that happened in this country.

Þiðreks saga.

|

| Multiple medieaval manuscripts are providing stories

about the Nibelungen.

An army of merited and self-appointed experts has been attempting to

take out the historical core of such literary renditions. However, all

these specialists soon must state that they have

to do with uneasy unravelling ‘adaptation on adaptation’.

Nonetheless, only a few philologists have been

contributing outstanding results

to disentangle this most popular German saga:

In 1931 Prof. Aloys Schröfl submitted that the

second part of the Nibelungenlied, known as Der

Nibelunge Nôt (Grimhild’s revenge and the Nibelungen

Downfall), cannot be the right sequel of the first (Sigfrid’s life and

death) for legendary coherency, because the

second one appears initiated by Pil(i)grim

von Aribon, Bishop of Passau on the Danube in 10th

century

for his special political ambitions in the Ottonian German period.

(Aloys

Schröfl: Und dennoch –

die Nibelungenfrage gelöst, 1931; Der

Urdichter des Liedes von

der Nibelunge Nôt und die Lösung der Nibelungenfrage,

1927.)

The lay actually refers to some topical cultural and

political contexts of 10th century, which,

however, had become less significant or obsolete already in

12th/13th century.

Furthermore, considering connotative

cultural and historical environment of Ottonian Empire,

Schröfl claimed at hand of the 13th-

century Nibelungenlied conclusive circumstantial evidence remaining in

its stanzas that

Pilgrim obviously intended to use a former contemporary version as ‘the

carrot’ for the

court of Hungary. With it, as Schröfl conjectures, Pilgrim

intended to enlarge his influence on this country

that was about to be christianised. According to this certainly

interesting context, the putative Ottonian version of the lay

could have been created to glorify the ancestors of the Hungarians and

might be evaluated today as an early political flyer.

The lay’s eldest extant manuscripts or ‘redactions’,

that might have been renovatingly written in the time of Wolfger

von Erla, Bishop of Passau, seem to reveal that this ‘regenerated

poetry’ came

into fashion at the beginning of the 13th

century. Thus, regarding characteristic plagiarism or ‘copying’,

assimilation and assemblage of compiled mediaeval

heroic epics, the postulated prime version must have been

transformed to ‘updates’ due to the spirit of high mediaeval times.

Yet, Schröfl’s research into the politico-religious

10th- century relations of German

Empire with Hungary is mainly focussing on connective approach

to motive and authorship which,

however, has been either scholarly suppressed or apodictically

negated through non-convincing Germanistic evaluation. Nonetheless,

Schröfl fairly underlined that the previous

creators of the Nibelungenlied are explicitly quoted in its Lament

work KLAGE as Bischof Pilgrin von Pazzowe

and his Master(-writer) Kuonrat.

Karl J. Simrock, well-known German translator of the Nibelungenlied,

has already connected both names with heyday of Upper German Clerical

Poetry of 10th/11th

century.

According to the studies of the most important 13th-

century manuscripts

made by the journalist and book author Walter Hansen (Die Spur

des Sängers, 1987,

p. 221f.), the narrative topographical details provided with the

verses on Kriemhild’s journey to Etzel may

intriguingly point to the poet’s location in today’s Low Austria,

whom he identified with Konrad von

Fußesbrunnen (re-)creating the lay in behalf of bishop

Wolfger von Erla.

Moreover, the literary scholar Peter H. Andersen, Prof. PhD, University

of Strasbourg, has recently recognized this Chuonrat von

Fuozesbrunnen as the most likely author, who already rhymed the

more than 3000 verse epic Die Kindheit Jesu and a secular

work in Wolfger’s time: Nibelungenlied

und Klage: eine niederösterreichische Doppeldichtung? in: Die

Bedeutung der Rezeptionsliteratur

für Bildung und Kultur der Frühen Neuzeit (1400–1750).

Beiträge zur sechsten Arbeitstagung in St. Pölten (May

2019), pgs 451–510.

However, due to research findings on the Nibelungenlied

and

the Dietrich von Bern poetry, a distinction must also be made

between archaic sources and contemporary motif structures that were

specifically implemented into the redactions of the high mediaeval

Nibelungenlied.

Heinz Ritter († 1994), philologist from

German

Schaumburg

on the Weser, seems to have uncovered the historical core of the ‘real

Nibelungen’

by his impressive publications and lectures. His long and meticulous

work,

done over many decades, led him to various Nordic texts, especially to

the manuscript known as Old Norse Membrane

(perg. fol. nr 4,

usually completed with younger Icelandic texts) and two Old Swedish

manuscripts which he

shortly called Svava. As

Ritter points out, these texts cannot

refer

to Theodoric the Great of Ravenna, but rather an equally named

Franco-Rhenish

king of Germanic Migration Era who had his first residence somewhere

between the Eiffel and the Rhine.

The Svava (or the Didrikskrönikan)

and the Membrane, popular name of the eldest extant manuscript of the Þiðreks

saga, provide narration about the historical Nibelungen, as

classified by progressive research that follows H. Ritter

(‘Ritter-Schaumburg’).

The Svava reports shorter than the more longwinded narrating Membrane,

but

both

versions relate quite more objective than the so-called MHG (Middle

High German)

sources. The archaic version of both manuscripts was certainly known

either before

or in the era of Charlemagne who had initiated the recording of

historical

traditions to great extent, as Ritter argues in his book Sigfrid

ohne

Tarnkappe, 1992.

This book reveals a very imposing correlation between

action

and topography

related to the Nibelungen, Sigfrid’s life and death.

The basic Evaluation of the Nordic

Manuscripts

Ritter’s

method of dealing with the Þiðreks saga is principally based

on his answer to the cardinal question whether a

tradition being assumed remarkably pregnant with historical

facts may be dissected in twilight mixture of mythological or

fabulating

narratives. As Ritter has expressively underlined at his

lectures, rather less significant as well as detectable

noncontemporary adapting implementation by an evident group

of Old Norse editors might have induced the majority of scholars

to estimate the Þiðreks saga basically as less authentic or

fabulous pool

of originally unrelated single tales. Furthermore,

Ritter regards the source of the Old Swedish manuscripts

principally ‘guiding’ Þiðreks saga, and he considers these

texts of such recognizable literary style and selectivity which

subsequently may allow efforts to estimate them as

historiographical sources.

Theodore M. Andersson, reviewer of a symposium based

supplement edited by Susanne Kramarz-Bein for Walter de Gruyter’s

encyclopaedia of Germanic antiquity, comments the contradicting

cataloguing of the Þiðreks saga.

Andersson was apparently remembering

Ritter’s publications with this introductory remark of 1996:

»...Þiðreks

saga, which had not

received much scholarly attention for several decades,

came back into fashion about ten years ago...«

This

English review, available at http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~alvismal/7susanne.pdf

(retrieved

May 2005), follows Heinrich Beck’s general position by means of (e.g.)

his

paper Þiðreks saga als Gegenwartsdichtung?

who, stringently against Ritter’s postulation and reasoning,

notoriously exposes the Þiðreks saga to the light of poetry

which appears somewhat and somehow inspired by history. Andersson

writes:

Heinrich Beck’s

"Þiðreks saga als

Gegenwartsdichtung?"

(...) points out that Þiðreks saga (...) synchronizes events

from legendary prehistory with near-contemporary events

in the twelfth century (campaigns against the Slavs on

the eastern frontier of Germany). Time in Þiðreks saga

is thus a variable quantity...«

Moreover,

Heinrich Beck classifies the message of Þiðreks saga

expressively more subtle than its naïve reader would

imagine. Obviously addressing Ritter, he underpins Germanism’s

fundamental attitude toward the general understanding of

SAGA with this manifesto:

»Germanistic

saga research has recognized long since (...) that saga

tradition is not an ancient forwarding but derives from topic

adoption.«

(Transl. from Zur

Thidrekssaga-Diskussion, in: Zeitschrift für deutsche

Philologie. 112, 1993, pgs 441–448.)

However, Ritter’s research does not disregard the fact that the Old

Norse scribes evidently processed to title translated historiographical

and chronicled material as ‘saga’.

Thus, in so far, critical research would be not satisfied

with some subtle or at least ‘very interpretative’ explorations of the

Old Norse

texts which have been provided by Heinrich Beck and other scholars

Ritter’s translation of the Old Swedish ‘Didriks chronicle’ was

not called in question on literary subject. For elaborating

research he therein left his comparing analysis of both

chronological and historiographical structures of the Svava

and the Þiðreks saga manuscripts. In the addenda provided

with

his translation (pgs 399–455) he calls into question

the Svava’s dependency from the Membrane

and Icelandic manuscripts against scholastic

evaluation of mainly Scandinavian researchers. He also implemented

into his posthumous publication Der Schmied Weland

exemplary synoptic studies that point out the different literary

styles of these texts which, for instance, provide the

Þiðreks saga’s predilection for certain subjective notional

forwarding and, presumably, for mythologizing.

Seasoned practitioners have not rejected Ritter’s methodical

deciphering of the geographical and ethnic names in the Didriks

Saga, an analysis of noteworthy consistency that considers

rational contemporary circumstances of time and location. In 1959

William J. Pfaff had already introduced an equally titled book

with a geographical study in Germanic heroic Legend, who, however,

failed in

geostrategical plausibilities when turning to the less believable

Ostrogothic milieu, as this has been scholastically but

undifferentiatedly attributed to the texts by means of Upper German

poetry in particular.

As regards the source material of the Þiðreks saga, there is

no evidence that the Old Norse

editors had done essentially more than a mere translation of an

imported tradition which appears as a Low German Historia

Dietrich von Bern

– even considering that, apart from only a (very) few cases of

Ostrogothic misunderstanding and misinterpreting, the translators

obviously never attempted to change the most important location names

which have been re-allocated plausibly by Ritter.

To boot, it seems implausible that the Old Norse scribes of King

Hákon IV would have had any good reason to implant any own

narration or compilation on such unfamiliar small locations

as Vernica, Thorta, Brictan,

such rivulets as Duna, Wisara, Eydissa, such

mountain forests as the Osning

and Valslanga.

The Nibelungen Origin Place

|

As Ritter refers to the Svava and the

Nibelungen by means

of his comprehensive publication Die Nibelungen zogen

nordwärts (Herbig,

1981), the Nibelungen home location as well as name giving to them will

be related to a rivulet called Neffel (*)

that springs in the outer

Eiffel near Zülpich. Thus, Ritter follows the localization of

Franz

Joseph Mone, Professor in history and eminent German philologist of 19th

century.

Zülpich:

Weihertor.

Photo by the author. Ritter identifies the Nibelungen residence on its

suburban location Virnich or Virmenich – on well known Roman main roads

of both Cologne–Trier and Cologne–Rheims. |

Mone explicitly favours the region of Neuss that, besides, the Frankish

historiographer Gregory of Tours

quotes Nivisium (Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der teutschen

Heldensage,

1836, p. 31f.) Henri Grégoire, another researcher and

philologist, has

connected

that subject with Nivelle, castle and town of Belgium. The

records

about persons of this place show epithet donation as Nivellung,

respectively Nibelunc (whom Charlemagne proudly called his

uncle),

as these names were given to Pepins in 7th

and 8th

century. (The Pepins were forming most influential ‘mayor-domus’ family

serving as Mayor of the Palace Charlemagne and other preceding

Frankish

rulers.) Grégoire, although trying a suspect relocalization of

Burgundia,

basically agrees with Emil Rückert who published in 1836 (in the

same

year as F. J. Mone) his ethnological and genealogical discoveries by

his

book Oberon von Mons und die Pipine von Nivella – Untersuchungen

über

den Ursprung der Nibelungensage.

Furthermore, Mone connects Gilibach rivulet, today called

Gillbach that springs

c. 20 miles to the north of Zülpich, with the original area of the

Nibelungen. The

district of

this watercourse was recorded Giliovi pagus, pago Gilegoui

in Middle Ages. Earlier spelling forms of this region called nowadays die

Gilbach are unknown.

Nonetheless, some reader may think of the origin location of Gibica

or Gibich, the

latter provided as Middle High German name of the ‘Nibelungen father’.

We may compare these name forms with the Niflungen progenitor

‘Gjúki’provided by the Heroic Lays of the Edda, and whom is said

to correspond to ‘Gifica’ in the catalogue of heroes called Widsith.

Challenging the findings of Grégoire,

Ritter recognizes the historical seat of the Nibelungen just 80 miles

farther

to the east, since an eye-catching number of location names in the

region

of German Zülpich must be seriously taken into consideration for

verifying

those Norse-Nordic texts related to King Gunter’s family. For example,

there is an old place called Juntersdorf, formerly spelled

‘Guntirsdorp’

(dorp = village). The name of the Grimhild’s

and Gernholt’s

maternal grandfather King Yrian (Irian), as provided by the Old

Swedish

manuscript A,

seems to correspond

well with a former location Iriniacum.

Heribert van der Broeck, author of 2000 Jahre Zülpich

(Publisher:

Kölnische Verlagsdruckerei, 1968) ascribes this name to a Celtic

individual Irinus. The

manuscripts remark also

that

Hagen’s father was originally spelled Elf, Elff(e) or Albe,

as this name appears closely related to Elvenich. In former

times,

this place was testified as Albinacum or Albihenae.

Van der Broeck

reckons this location to a Celtic place of worshipping, since those ‘nich’

or ‘ich’

endings are very typical for Roman-Celtic

influence

on contemporary spelling.

Old settlements called Vernich

(etymologically

based

on a Roman

fundator called Varinius?), Virnich (at Zülpich-Schwerfen) and Virmenich

(now Firmenich) can be found there. These names correspond well with

the

Nibelungen residence originally spelled Vernica, Verniza, Vermintza.

Ritter does also detect a correlating basic item which

indicates the region of

Zülpich as the original home location of the historical

Nibelungen: The

manuscripts

note brightest full moon night when this folk met the Rhine at Duna

Crossing

on their fateful march to Grimhild and her spouse Atala (‘Attila’,

Old Swedish Aktilius, Atilius, Icelandic MS B: Attala),

king of that part of Saxony which

the Old Swedish scribes call Hunaland:

Since important campaigns were usually planned to start at full moon in

Late Antiquity as well as mediaeval times, the Nibelungen with

polished

armour underneath their garments could have covered only c. 30

miles

from

their capital place!

The Nibelungen region of Zülpich and Nivisium,

recognized by Ritter,

Mone and other researchers, formerly pertained to eastern Frankish

territory.

Regarding spatiotemporal history, a 5th–6th-century

ruler called King Sigebert – Gregory of Tours remarked him ‘the

Lame’ – was residing at Cologne before he was eliminated by Frankish

king

Chlodovocar I (‘Clovis’). The Waltharius,

a

poetry definitely elder than

the

Nibelungenlied, titles the Nibelungen as leaders of a Frankish tribe.

Thus,

we should make an effort to encounter Meroving(ian)s

by the Svava in the early history of the Franks.

Regarding research into the early history of Pepin Family, some more

interesting indications should be considered for correlation with the

Nibelungen

history:

| 1. |

The Pepins are undoubtedly

related to the region of Zülpich.

For example, a former church of Juntersdorf (Guntirsdorp) was dedicated

to their patroness Gertrud of Nivelles. |

| 2. |

The Svava and Membrane texts note Hagen’s son

Aldrian,

the only known

descendant of the Nibelungen, as a long living successor and ruler of

their

realm. |

| 3. |

The western borderline of the Nibelungen realm

was not

noted, but Sigfrid

(Aldrian’s slain uncle) could be considered heir of maternal family

property.

|

|

|

|

Juntersdorf:

A view

from the Neffel to the landscape.

|

Virnich.

|

|

Photos by

|

the

author. |

|

|

Irnich, suggested by Ritter, but etymologically less likely.

|

Virmenich

Castle.

|

The Svava quotes about the last ride of

Nibelungen

– the

undercover

campaign to their downfall – with this text:

...so they rode to the

Rhine, where Duna meets the

Rhine...

The Duna may not be taken for the Danube in this

connection,

rather

for Dhünn river (recorded as Duone in 1117) falling

till 1830/1840 into the Rhine at Leverkusen, the town to the north of

Cologne.

Incidentally, Ritter underlined this location as an important crossing

point

in former times.

The Niflungen then moved to Margrave Rodinger's seat.

Just south of the Dhünn dam was an early medieval settlement at Bechen.

A Bekelar

or Bechelar – name-giving was

the once

flowing Beche there – results with the ending ‘lar’ in preferred

meaning for a mostly water-related or swampy forest area. The other

local meaning of this old-language ending refers to a delimited area.

This Beche, so the medieval

place name, had a special strategic importance, because here was a

roadblock, a border marker in the form of a modernly called Landwehr on the old

army route from

Cologne via Wipperfürth to Soest. So we may this

location compare with the derivation of (lat.) Praeclara for

Pöchlarn to Bechelâren

on the Danube, as

propagated from the Nibelungenlied as the literary original. The

Germanist and Scandinavian medievalist Andreas Heusler recognized in

the Þiðreks saga, respectively its source material, a

preliminary stage of the Nibelungenlied, cf. Hans Peter

Wapnewski, Deutsche Literatur des

Mittelalters. Ein Abriß. Göttingen 1960, p. 71.

Other researchers generally agree with Ritter. For

example, Walter

Böckmann,

book author and documentary film maker, and Ernst F. Jung, historian

and

philologist, largely share Ritter’s revision of a more authentically

appearing

history of the Nibelungen or Niflungs. The Germanist and medievalist

Roswitha Wisniewski

found narrative

indications that

in

first half of 13th century a comprehensive

manuscript,

dealing

with the vita and epoch of Dietrich von Bern, was transferred

as

a chronicle from Westphalian monastery Wedinghausen to

Scandinavia

where it was re-narrated by Old Norse and Icelandic writers, as the

authoress

notes well in her postdoctoral thesis. As already mentioned, these

mediaeval scribes used to title imported historiographical material as saga.

|

|

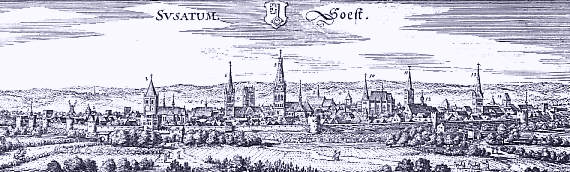

Soest

by Merian.

|

The Svava: Sigfrid

(‘Sigord’)

and the

Nibelungen

A short summary

Note: ‘Svava’ means the

the region of the northern Suevi whose settling territory might

have

included the region between Bode and Saale rivers in Migration Period.

| Sigfrid’s father Sigmund is king of Tarlunga.

(Nowadays, the

Low Saxon towns Wolfsburg and Braunschweig may be found in this

region formerly called ‘Darlingau’ and ‘Derlingau’.)

Sigmund enters in matrimony with Sissibe,

daughter of King Nidung

of Haspengau: Hesbaye, the region on the Meuse (Maas)

between

Namur and Maastricht. King Sigmund receives the half of King Nidung’s

realm

as gift. Sissibe, however, becomes victim of an intrigue initiated by

the

noblemen Hartwen and Herman. King Sigmund, who went out

to

warring, had appointed them to his representatives. However, Hartwin

will

annex Tarlunga with Sissibe for his spouse – but she refuses all the

time.

The counts pretend infidelity of Sissibe to their returning king who,

deeply

shocked, allows them to abandon her somewhere in a woodland. There, on

a river, she gives birth to Sigmund’s son. Hartwin will cut out her

tongue,

but his accomplice Herman will not agree with mutilation. In the end,

he

can behead Hartwin in a fierce fight who, however, has kicked the baby

– embedded in a vessel of glass – into the river. Sissibe, mentally and

physically stressed, dies of shock.

A hind finds the baby and breastfeeds it. Then a

smith called Mymmer (Mime) raises the

child

the Old Swedish texts call occasionally Sigord Swen1.

Sigfrid’s choleric nature is certainly basing on

frustration by the ‘gilded cage’ his childless foster-father Mime2

has obviously made for him. At the forge, he lets off steam by beating

up Mime’s best foreman. Mime has also to recognize that his huge

and

strong adoptive son would never become a good smith. Moreover, Mime’s

customer

Queen Brynhild (Brynilla or Brynilda in the Old

Swedish texts)

seems to attract his pet. In the end, Mime has to admit

that he cannot hold Sigfrid any longer, but he rather wants him dead

than

having lost: So the sly smith sends Sigfrid for charcoal burning to the

area of Regen3,

who was believed Mime’s brother as well as man-killing

dragon-worm.

Sigfrid meets Regen and kills him. (The cheeky

young man

certainly knows

that there is no witness to confirm his version that the bloody

brew4

from Regen has made his skin not only horny and invulnerable, but also

sharpened his mind to understand bird language.)

Sigfrid brings Regen’s ‘special head’ to Mime and

tells

him to pick

it. Mime, however, is tremendously afraid of expecting Sigfrid’s

revenge.

Therefore, he promises him a precious armour he has just made for a

king,

his best sword Gram(er), and Grane, a stallion

from the

stud

of Queen Brynhild.

Sigfrid takes the byrnie that Mime puts him on.

The

smith also hands

him over the sword, but Sigfrid swings Gram to kill his

foster-father.

Thereupon he violently enters Brynhild’s castle

to get

the stallion.5

After he has killed seven gate guardians and scuffled with the queen’s

knights and squires, she manages to stop him. Much impressed by the

intruder,

she sends for the stallion and enlightens Sigfrid about his

descent.

Sigfrid moves with Grane to Bertanga,

a spelling form of German Bardengau,

today the region between Hamburg and Wittingen on Elbe river. He there

takes up service at King Isung who allows him to bear his own

shield

banner, which shows a dragon, in half red and half brown, on red

background.

King Theoderic of Bern6

(Didrik by the Svava)

receives information about Sigfrid’s power

and heroic actions. He makes up his mind to go out and measure himself

against him. These are some of the Twelve of his followers: Gunter

(in the manuscripts Gunnar), king of the Niflungs

(Nyfflinga, Niflunga), his brother Gernholt,

both sons of King Irung (Mb 2), and their half-brother Hagen,

the Old Norse Hǫgni7. Heim the Magnanimous,

or the Fierce,

is mentioned as a relative of Brynhild. His blue shield shows a

stallion. Wideke,

son of Weland, is the owner of Mimming (Mimung), the

legendary

sword

already made of hardest steel. Incidentally, as the Didriks chronicle

also

remarks,

Sigfrid’s cockiness had turned out Weland, creator of Mimung,

from

Mime’s smithy.

Didrik camps within sight to Isung’s castle8.

Sigfrid masquerades as modest horseman and rides down to spy them out.

He demands an appropriate present (‘toll and tribute’) from the

arrivals

for his king. Didrik’s noble knights throw dices for it, and Sigfrid

receives Amling’s horse and shield. However, Amlung follows

King Isung’s special

agent with Wideke’s white horse Skimling to get back his own

whatever

may come. Sigfrid defeats Amlung as they meet in the woodland nearby.

He

discloses his identity to his pursuer, and gives back the horse to its

owner because he remembers Amlung’s father Hornboge as

good

kinsman. Wideke had also recognized Sigfrid, but both do not report on

this incident to the Franco-Rhenish king.

King Isung agrees with a tournament. He nominates

his

eleven sons and

Sigfrid. Didrik cannot defeat him with his sword on

first

and second day. Therefore, he goes to Wideke and insists on handing

over

the Mimung. At the beginning of the third day of tournament, Didrik

swears

off to use that sword, but takes it nonetheless.

After King Didrik has seriously hit Sigfrid five

times,

the beaten recognizes

the wilful deceit and surrenders. For all that perjury, Sigfrid freely

offers his service to the Franco-Rhenish king.

Sigfrid enters in matrimony with Grimhild

(Crimilla in the Old Swedish texts)

by instigation

of his new king. As doing so, Sigfrid receives the half of the Niflungs'

realm that King Didrik has promised him.9

King Sigfrid, just married, loves to be the broker

for

the marriage

of King Gunter and Brynhild. This service is delicate insofar as

Sigfrid

had sworn her faithfulness before his own marriage, and so she gives

him

now a good talking to his broken oath of love!

The kingly marriage was performed between Gunter

and

Brynhild, but she

successfully refuses every night. Gunter confides his problem to

Sigfrid

who discloses that she might lose her power at her first physical

contact.

Gunter thus entrusts Sigfrid with further proceeding. However,

Brynhild

does not refuse against Sigfrid.

Grimhild later finds Sigfrid’s trophy of that hot

lovers' tryst: Brynhild’s

ring. It triggers off dispute and deepest odium between Grimhild and

Brynhild.

In the end, basically in parallelism with the Nibelungenlied, Sigfrid

will

be killed by Hagen’s spear.

Grimhild swears revenge and marries King Atilius

(in other texts Attala, Attila).

He is descendant of a mighty Frisian

ruler family and the ruler of a large region belonging to today’s

Netherlands and Low Saxony. Seven years

later, she attracts her brothers to meet her at the residence of her

spouse: Susa(t)

(Soest of German Westphalia), centre of the so-called Hunaland

or Hymaland.

King Gunter combines the great chance to take over

the

realm of his

brothern-law, although Hagen and Queen Oda warn him in vain. So the

Niflungs

finally accept the invitation and move out with 1,000 fighters. Hagen

meets

two fortune telling women on that ride at a river lake on the Rhine. He

slays them after a trivial dispute about their ominous prophecy, and,

only

a short time later, the ferryman at Duna mouth crossing point.

After a half day ride, the Niflungs meet Margrave

Rodinger (the Old Swedish Rodgerd)

at Bakalar (‘Becculær’, ‘Pæclar’ in the texts) that

Ritter

identified in today’s region of Bergisch Gladbach.

After a short stay they follow the Duna (dwna), passing Thorta

(Dortmund) on their route

to Susat. There the fate of the Niflungs is sealed in the

heavy

battle

against the folk of King Atala, who, nonetheless, must give the lives

of

4,000 fighters for his victory.

At the banquet, where Providence was tempted,

Grimhild

wins her little

son Aldrian to punch on Hagen’s chin for funny encouragement.

However,

the irritable Niflung becomes so tremendously enraged by the boy’s

action

that he beheads him and his tutor. In reply, King Atala gives

immediately

order to slay all Niflungs.

Already on the first day of the battle, Gunter

must

surrender to the fighters of Duke Osid, nephew of Atala.

They throw him into the Schlangenturm (Snake Tower,

apparently not far from the so-called Irungs Wall)10

by order of Atala, where the king of the Niflungs

dies.

Thereupon Didrik slays Grimhild on Atala’s

demand.

Hagen, seriously

wounded by Grimhild’s loyal follower Lord Irung whom he had slain,

surrendered to Didrik after

his last fight against the Franco-Rhenish king, who, nevertheless,

cares

well for him. Hagen wishes for a young woman to be his nurse. He is

able

to beget a son in the last night of his life, and hands over the keys

to

Sigfrid’s Hoard to the expectant mother of the child, a promised son to

be named Aldrian.

Young aged, about 12, Aldrian attracts King

Atala, his

aging foster-father,

to that three-doors treasury cave and locks him there. Thereafter

Adrian

reports this revenge of the Niflungs to Brynhild who rewards

him

generously. Then he takes over the Nibelungen realm as good king.

The location of the Niflunga Hoard11

was kept as a secret and the cave never entered again. Its position

cannot

be estimated being far from King Atala’s residence.12

|

Annotations: Questions & Findings

|

Nordharz

Map of 1968 |

|

*

Neffel - Niflung

According to German Wikipedia ‘Neffelbach’ (retrieved

2012-07-26),

the name of this rivulet is based on Nevvel =

fog,

because ‘the banks

of this stream are frequently covered with fog in the morning’. A

legend rooted in the region of the rivulet’s source tells about two

influential underground dwarf rulers Niff

and Neifel.

Obviously picking up this context, the Nibelungenlied provides a more

or

less splendid allusion with two dwarves called Nibelung, father

and

son. The latter had a brother called Schilbung, possibly

derived from a

place named Schievelsheide nearby. Their father left

an immense treasure captured later by Siegfried.

Interestingly, the 350th stanza of the

Nibelungenlied reads Nebelkappe (= fog

cap)

instead of Tarnkappe (= stealth cap): ...with

it everybody could do anything of his courage

– apparently a further allusion to this Neffel region. (It seems also

comprehensible that dense fog can make particular smaller

creatures less visible.)

The author(s) of the

elder Waltharius,

Upper German poetry ascribed to 9th

or 10th

century, nicknamed the Nibelungen Franci nebulones.

A rather objective initial interpretation that unmasks the Neffel dwarf

legend follows ore processing being proved there at an early date, in

this

region already applied in Roman times. Thus, it seems consistent that

small people

simply called dwarves did their jobs in underground mining or

‘in the caves’.

And they might have been commanded by those potential, smart and

skilled

individuals of same body size who were masterly engaged in profitable

iron and fine art metal works.

Regarding the etymological side of word forms beginning with nifl-

, Jan de Vries rightfully connects original

meaning with both dark and foggy, as the former

adjective

might correspond well with traditional mining work in this region (J.

de Vries: Altnordisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch). |

|

In comparison with Heinz Ritter’s localization of Sigfrid’s childhood

and

forging episode, dragon fight and treasure capture (see annotations 1

to 3),

the Neffel region as well as locations called Rheinbach (early

recorded as Reginsbach) and Wormersdorf,

both nearby, seem to gain in archaic background.  |

1 Sigfrid

His birth and fate as a baby appears as

an adaptation

of Frankish Genoveva legend enriched with motives of the birth of Moses

and the saga of Romulus and Remus.

Ritter pleads for the northern Harz as the venue of

Sigfrid and Mime the Smith, as he points out a deserted

settlement Siewershausen

(see X- mark on the linked Nordharz map) which was named originally Sigefrideshuson

maps.

|

|

Siewershausen,

deserted

settlement. A view to SE.

Photos

by

the author.

|

Minsleben

– "Mynnersleben"

on the Holtemme rivulet.

A

view to

the mountains

where to find the rocky ground of Ilsenstein Castle.

|

Sigfrid’s Size

Mime takes a byrnie he has just made for a king, puts

it on

Sigfrid,

and it does fit. Moreover, it obviously fits so well that he can move

with

it to Brynhild’s castle. If he were aged as a boy, he could certainly

not slay seven guardians and go at loggerheads with some knights and

squires

on the queen’s castle. What are the mathematical probabilities that

both

the king and Sigfrid may have same size of just about a giant’s? There

is much impressing description of Sigfrid’s size, as Lord Brand recites

at the Grand Banquet for King Didrik’s followers and friends (Sv 177&178).

Does that speech might rather spring from boating yobbos who are much

overrating

themselves? Only a short time later these guys have go home with a

shaming

man-to-man result of a trial of strength at King Isung: They had lost

not

less than nine of twelve fights! Besides, Hagen and King Gunter were

defeated.

Didrik’s fight may be left aside here for his wilful deceit by broken

oath.

2 Mime

Mime seems not to be an any old smith who has to do his

every

day’s job

for the villagers. Rulers of far regions obviously know about his

excellent works.

Sigfrid does not belong to the workers of Mime.

Obviously frustrated by hanging around, Sigfrid pokes his nose into the

smithy now and then,

where he does nothing else than vastly enervate and beat Mime’s

workers.

Just at that point, as Sigfrid was hardly to control for his enormous

puberty,

Mime is going to teach him working at the anvil.

According to early documented testimonies, a village

called Minsleben, a few miles far from Siewershausen, does

belong not only to the

eldest settlements of that region, but is also closely related to iron

works of early times. Ritter was witness of scientific diggings and

analysis

of ferrous slag found at Minsleben, whose suffix leben is a

derivation

from Thuringian leva or leven. Ritter

notes well that Mime was written down as Mymmer or Mynner

in

the Old Swedish manuscripts.

Another intriguing localization of Mime’s smithy has

been

pointed

out by

Rudolf Patzwaldt:

Referring to the Reginsmál and Fáfnismál

of the Elder Edda (Codex Regius), a ruler named Hjalprek

put Regin(n)

(intertextual

character corresponding with Mime) in charge of raising up Sigurð.

Regarding Ritter’s timline of Þiðreks saga, this Hjalprek

may

be considered as the early Salian king Childeric I. Both

historiographical

and poetical texts localize his activities also in Saxony and

Anglo-Saxon campaigns.

Following the texts written by Gregory of Tours, Childeric’s territory

or influence might

have included the Eiffel. Regarding that passage provided by

the Elder Edda’s lays, we could identify the

Eiffel locations Worm ersdorf

and Rheinbach, the latter formerly

certified as Regin(s)bach

(= ‘Regin’s rivulet’), as place of Sigfrid’s foster father. This

implicates in so far an important area of narration provided

by

some heroic lay of the Edda.

On the subject of the slaughter of Sigfrid, Patzwaldt

also

focuses on

intertextual etymological details provided by the Nibelungenlied and

Þiðreks

saga. Subsequently, he points out the Eiffel as more believable origin

location of some of the lay’s most dramatic parts.

3 The Regenstein,

the venue suggested by Ritter

Seven miles to the southeast from Minsleben, the Regenstein

rises

up as a small woodland mountain with steeply ascending rocks.

|

|

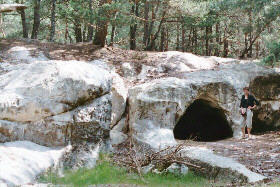

The

'Feuerland' forest

surrounds the Regenstein. Photo by the author.

|

Imposing caves are crossing the Regenstein foot area

that is

nicknamed Feuerland (Fireland).

They could have been serving for places of Germanic worshipping, e.g. Thing

ritual.

|

|

|

Photos

by the author.

|

|

Today, just a mile far from the Regenstein, ponds and

marshy

places

fill the little valley of Goldbach rivulet. Old land registry

maps

specify its parcels as Drachenkopf (Dragonhead) and Drachenloch.

The

latter, ‘Dragon Valley’, rolls approximately a third mile.

Forest

rangers of this district still use these names. Today, this area is

privately

run and restricted.

|

|

| The

impressing ‘Dragon Valley’ rolls about a third mile. |

Photos by the

author who thanks the proprietors of this

land for

the release of both photos. |

Was Regen a solitary protozoon or the Count of

Regenstein?

There might have been an ideal habitat for the first

named

possibility.

Although the manuscripts report on Regen as a brother of Mime, this

context

could mean spiritual brotherhood: Had Mime some slyness and cunning of

a reptile?

On the other hand, Hatebold alias the first Count of

Regenstein (s.

below), a homeless parvenu who recently had received that location

probably

without remarkable means, could easily and specially protect his area

by

making good use of the ghastly natural scenery surrounding his castle:

As most important performer, he just needed the completing ‘dragon’ to

horrify (and rob?) unexpected visitors – certainly by masquerade. There

are some tortuous items supporting such theory of an unreal dragon, cf.

original quotations in Sv 158 and Sv 304.

The German translation of the Vǫlsunga saga, 18,

quotes

this speech by the ‘dragon’:

Haven't you heard how

that all folk was afraid of me

and

my shocking

helmet?

[Translation by the author.

However, the Vǫlsunga saga translators

William Morris and Eirikr

Magnusson

(Walter Scott Press, London, 1888) like to give less exact translation

by this speech of Fafnir: Hadst thou never heard how that all folk

were adrad of me, and of the awe of my countenance?]

A robber masqueraded as a dragon, as some authors

conjecture,

would

never dare to chose his hidey-hole on the foot of a feudal lord’s

castle

or somewhere nearby; and a wary Mime, heaping up an enormous mass of

profit

by his ‘High-tech smith works company’, would never entrust neither a

robbing

kinsman nor any unfamiliar person with that means in order to keep it

far

away from his questionable or curious workers and, generally, any kind

of temptation. Nonetheless, Mime would certainly do accordingly with

his

brother who ought to meet contemporary VIP class as well: Regen – Count

of Regenstein.

The above mentioned passage of the Vǫlsunga saga

enlightens

us

on the incentive related to the smith and his brother. The latter or

the dragon-worm, basing on narration by Fáfnismál

of

the Elder Edda, makes this confession toward Sigfrid

who

has wounded him lethally:

I had on the shocking

helmet to protecting myself

against

all folk

for all the time I was keeping my brother’s heritage... so that nobody

else dared to approach me; no sword was frightening me, and I never

found

so many men against me, methought being much stronger than them, so all

were afraid of me ... (Translation by the author.)

However, the Vǫlsunga saga

provides a divergent

background

of the ‘brothers heritage’.

|

|

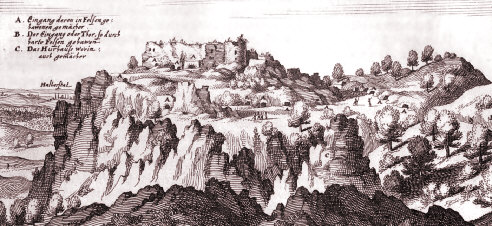

The

Regenstein with

its ruined castle by Merian, 1654.

|

|

There is historical narration about name

giving to Regenstein:

In 479

Malvericus, King of Thuringia, started a campaign against the Saxons.

However,

his army was beaten back at Veckenstedt (Veckenstädt) in the Harz.

There, a brave fighting nobleman called Hatebold was rewarded for his

service by the option to chose a piece of land for his own

residence.

When he

found the little rocky mountains, he shouted out: ‘This stone is

the

right (= regen) one for my home!’

After

he had built his castle there, he called himself ‘Count of Regenstein’. |

| |

| Source: Sagen

um den Regenstein by Hans Bauernfeind, Helga Sorge, Hermann

Wehr. Publisher: Schloßmuseum Blankenburg. |

|

Thus, the name of this location was contemporarily known. If just a

huge

reptile

were living at that time somewhere around the Regenstein, it could have

been

easily

named after the short name of its proprietor.

4 Dragon’s

Blood on other spots

Regarding the legendary incredible qualities of

Sigfrid’s

skin, the

Svava itself qualifies all those quotations to a reasonable degree when

retelling the tournament fight against Didrik, where Sigfrid, even

protected

by a byrnie, must give up for his wounds!

Incidentally, by retelling his fable of the

‘Dragon Killer’ who

had taken that special bath from the beast’s bloody brew, Sigfrid

could certainly make some people believe to have become an invulnerable

superman

just by this thrilling excuse: As historians have noted, the

Merovings,

most important dynasty of early Frankish rulers, were tainted with

hereditary

skin disease called ichthyosis hystrix. Its most striking form will

make

human skin as thick as a swine’s rind. This seems to correspond well

with Sigurðr’s Old Norse apposition sveinn

which, however, is also the word just for a boy rather of bad

appearance.

This is translated text from the entry Drache

= Dragon

by German DUDEN, Edition 1969:

...The victory over the

dragon means victory over chaos,

darkness,

or an old order...

Thus, the dragon represents the bad – and he must not

necessarily come

out by its natural appearance!

|

|

The

'dragon-worm'

as being placed on the Drachenfels ‘Dragon Rock’ on the Rhine.

|

|

Incidentally,

this

protozoon sculpture is a detailed reconstruction basing on real

skeleton

fragments preserved at Senckenberg Museum, Frankfurt, and the Berlin

Zoo.

|

|

Photo

by the author.

|

Francis P. Magoun Jr reinspected

the Old

Norse ‘itinerarium’ Leiðarvísir og Borgarskipan

written by

Nikulás Bergsson (Bergþórsson). The abbot

of Munkaþverá connected the Gnitaheiðr,

where Sigurðr killed ‘the dragon’ by

traditions based on the Edda

lays, with places called Horús

and, as nearest site to the venu, Kiliandr,

explicitly on a route between Pǫddibrunnar

(Paderborn) and Meginzoborgar (Mainz). The American scholar

recognized Horús as Horohusum at the

northeastern foot

of the Eresburg at Obermarsberg, its mediaeval

settlement now

deserted but already in a certificate by Emperor Otto I,

afterwards by

Henry II, cf. also

Hermann Oesterley, Historisch-geographisches

Wörterbuch

des

deutschen

Mittelalters, 1883: 302. Magoun thereby

hazarded the

hypothesis that

the latter site Kiliandr could be

identified with Kilianstädten on the Nidda (obviously

likewise Rudolf Simek, Altnord. Kosmographie, RGA Erg.-Bd.

1990:484; cf. a

review by Dominik Waßenhoven 2008:29–61).

Magoun estimates most tentatively that

this valley region with suggested mediaeval name forms like Nitahe

or Nitehe

might have stood for the heiðr’s

Icelandic understanding.

Nonetheless, we may wonder whether this location on the

Nidda does also provide a reflection of the eminent Nidhogg

of Old Norse mythology. Apart from that, however, we may take note of

E. C. Werlauff: The editor and publisher of

the Symbolas ad Geographiam medii ævi ex monumentis

Islandicis (1821) likes to connect Kiliandr

with Kaldenhart, the former name of Westphalian Kallenhardt,

east of Warstein (cf. below). Sigurðr’s

decision to slaying also his foster-father, the obvious

last confidant knowing of Fáfnir’s place of treasure,

could point to the plan to carry off the treasure impromptu and

secretly to a hiding place nearby.

Felix Genzmer

(Berlin 1927) supplements the slaying of Fáfnir with a

passage

taken from the Vǫlsunga saga which is quoted here with the translation

by Magnusson & Morris:

| Then Sigurd leapt on his horse

and rode

along the trail of the worm Fafnir, and so right unto his

abiding-place; and he found it open, and beheld all the doors and the

gear of them that they were wrought of iron; yea, and all the

beams of the house; and it was dug down deep into the earth: there

found Sigurd gold exceeding plenteous, and the sword Rotti; and thence

he took the Helm of Awe, and the Gold Byrny, and many things fair and

good. So much gold he found there, that he thought verily that scarce

might two horses, or three belike, bear it thence. So he took all the

gold and laid it in two great chests, and set them on the horse Grani,

and took the reins of him, but nowise will he stir, neither will he

abide smiting... |

The Leiðarvísir’s

intriguing passage was already challenged by Paul Höfer in 1888

and Otto Höfler (1959,1961,1978) who turn

to the

Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in order to identify Arminius with

Sigfrid and the ‘dragon’

with the Romans (most extensively Höfler). However, both scholars

and their modern followers propagate less convincingly the Knetterheide

at Schötmar (Bad Salzuflen) which is on a route

rather from Mundioborg (Minden) to Pǫddibrunnar

(cf. e.g. Heinrich Beck 1985:92–107).

The Vǫlsunga saga considers the Hindarfjall in

narrative

environment with both Sigurðr’s

fight

on the Gnitaheiðr and Brynhildr’s

seat. Regarding this geographical context, the author received between

March 2012 and 2014 an interpretation from the philologist and book

author August Hunt who follows Magoun on Gnitaheiðr and

estimates Seeburg on lake ‘Süßer und Salziger See’ as Brynhildr’s

primary residence. Mentioned in A.D. 1043 as lectulus

Brunhildi, the Großer Feldberg in the Taunus

mountains

does remember the heroine long since with the so-called Brunhildisfelsen,

c. 30 km (18 mi.) far from Kilianstädten. For the ‘Hirschkuhberg’ =

Hindarfjall

associated with Brunhild’s seat, there is also – only a few kilometers

east of Bad Honnef – at least a name similarity for a mountain that was

later renamed Himmerich; cf. Johann Joseph Brungs, Berg-

und Flurnamen aus dem Bereich des

Siebengebirges (1931) pgs 12–13.

Interestingly, as regards Sigurðr slaying Fáfnir

on Gnita heath, it

seems less likely that Nikulás had known the Nibelungenlied.

However, he notes the Italian thermae Þiðreks

bað at Viterbo (→

Bagnoregio,

formerly the 6th-century Balneum

Regium) which he quotes or suggests as a plausible

health resort of the Italian king Theoderic the Great. The Old Norse

scribe of the Þiðreks saga could have remembered this passage

of the Leiðarvísir

in so far,

albeit there were at least to well-known spas in the kingdom of

Frankish king Theuderic: Aquae

Granni (Aachen) and the thermae of Roma Secunda (Trier).

5 Brynhild’s

Castle

After Sigfrid had slain the ‘dragon’, he moved with a

byrnie

from Mime’s

smithy straight to Brynhild’s residence Seaguard'in Svava.

Ritter identifies

the smith near

the Regenstein on the north side of the Harz. Consequently, apart from

a possible seat in the Taunus and Seeburg

in northern Suebia of Migration Period (reasonably suggested by A.

Hunt),

the other nearest

castles would be either the Heimburg (H. Ritter) or Ilsenstein (W. Böckmann);

the latter on a mountain in the neighbourhood of the highest mountain

of the

Harz:

the Brocken with its marvellous sight-seeing place. Incidentally, the

Nibelungenlied

provides Isenstein as Brynhild’s residence. According to the

Old Norse Þiðreks saga, she had also a stud estate in the

forest

nearby, whose horses were much praised for their extraordinary

qualities.

Queen Brynhild is known as an orphan. Her uncle – who

rather

might be

her brothern-law – is Heim (the) Studder or Heimir.

He

runs her stud estate, as provided by the Vǫlsunga saga

that

nicknames Brynhild’s castle Shielded Castle or Castle of

Shields.

Its rocks photographed from the distance seem to resemble simple

shields

of Late Antiquity being heaped up irregularly. The position of Heimir’s

castle, the Heimburg which became related to German rulers

Henry

IV and Henry the Lion later on, can be verified by a large lake

– ‘sea’

(See) in German language – recently found subterranean only some

miles to the north, as the proprietors of Dragon Valley land

parcel

informed the author.

Nonetheless, Queen Brynhild might have had no reason to

give

up the I(l)senstein

after the death of her parents and move down to her bad- tempered

relative

on the lower Heimburg (Sv 14), as Walter Böckmann does also

believe.

This castle might belong to the queen’s real estates; but the

‘Isenstein’,

with its surviving rocks and longwinded access of nearly one mile, is

in

quite more representative landscape position.

|

|

|

Amid

the photo: The

Heimburg cone at an important strategic position.

|

The

Harz rising behind

the Heimburg.

|

All

photos

by the author.

|

|

|

Horse

Capital of

Drübeck Crypt.

|

The

Heimburg by Merian,

1654. Ground

Plan

|

The traditional but peculiar horse breeding in

woodlands

and forests,

as Tacitus quotes in his Germania, ch 27, is also shown by the Horse

Capital at the crypt of Drübeck Cloister Church

founded c. 2 miles far from the Ilsenstein. Incidentally, the distance

from this place to the Heimburg is approximately 9 miles.

6 Theoderic or

‘Didrik'

of Bern’

He was proclaimed King of Bern at an age below

20.

Already grown older, he has to flee to King

Atala who grants him exile at his Soest (Susat) residence

for a big threat coming from Didrik’s kinsman

Ermenrik. Now, in the period of deprivation,

Didrik seizes the opportunity to aid Saxon

King Atala warring against Baltic tribes. Thereafter he leaves

Atala’s court for a campaign against Ermenrik.

However,

the battle at Gransport on the Moselle’s mouth results in

Didrik’s

high personal losses. He moves back to King Atala and

renounces his restoration to the throne for the deaths of a

kinsman and two offspring of King Atala’s family.

Some years later, after the downfall of the Niflungs

at Soest, he leaves King Atala’s country for Bern where he

goes out

with his new army. He meets the troops of Sevekin, Ermenrik’s follower,

at Graach on the Moselle and

overthrows him. The scriptors relate that Didrik was immediately

crowned King of Rome (= Trier),

thereafter

ruling even a greater

realm.

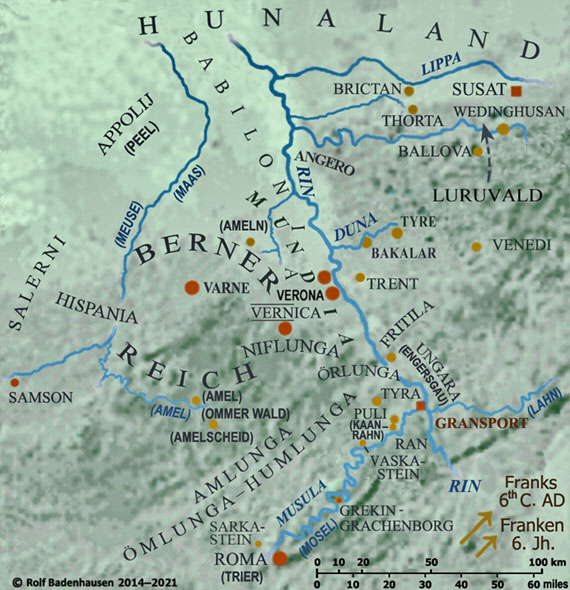

Some locations of Þiðreks saga

(Ritter and

other authors).

Some locations of Þiðreks saga

(Ritter and

other authors).

Ritter believes in Bonn on the Rhine as place of

residence of

young King Didrik. He argues that Bern is based on derivation

from

Latin Verona - Berona as handed down actually in the

Middle Ages

for Bonn on the Rhine. Nonetheless, we seriously have to consider

another

quite more precious ancient place for Bern: ‘Varne’, provable

short

spelling

of the Roman VARNENVM.

Another

location appearing between Atala’s residence and Didrik’s Bern is Babilonia.

It can be identified as Cologne on the Rhine by clerical messaging of 11th-German

century. Thus, the basic

connections

related to the vita of Franco-Rhenish king Didrik cannot be confused

with

those of Theodoric the Great.

7 Hagen

Hagen’s father can enter the garden of certainly well

guarded

kingly

castle without any problems for a lovers' tryst! Therefore, he

certainly

had been introduced to the court, coming across with self-confidence

and

auspiciousness

as a druid (Sv 161). The appearance of a Celtic priest in the Eiffel

region

of the Niflungs might correspond with those typical

spelling

relicts in today’s location names there. The former location of Hagen’s

family, as provided by his name apposition he certainly had received

from

his father, is occasionally forwarded as ‘of Tröya’ (Sv 340) or

‘of

Troja’ (Þiðreks saga, Mb 395). However, it seems less

credible that

Hagen’s

ancestors were of Trojan origin or came from the Colonia Ulpia Traiana

of Xanten. We rather should consider Frankish Troyes,

Champagne-Ardenne,

outstanding Celtic location of the Tricassi.

The old spelling form ‘Hǫgni’, with a

lower-o-ogonek, is commonly typed ‘Hogni’.

8 King Isung’s Land

... They were riding across large woodlands and

heaths ...

The Svava’s description perfectly corresponds with the

heath

lands of

German Lüneburg. Ritter estimates the kingly castle on the Kalkberg

of Lüneburg town.

|

|

The

Kalkberg of Lüneburg

by Merian.

|

Incidentally, Sigfrid reports to King Isung that on the

shield

of one

arrival is also a lion of gold with a crown (Sv 185).

Since

there was no other subject mentioned afore being in connection with

this

symbol, it must be King Isung’s, too. Actually, we know dynasties with

a lion on their heraldic crests that have been ruling this region

between

Brunswick and Lüneburg.

9 Sigfrid and

Grimhild

(and King

Atala)

The Svava does not report on any affections for a love

match

between

Sigfrid and Grimhild!

Due to Ritter’s timeline of the Didriks chronicle,

Grimhild

was aged

over 40 when she married King Atala. Considering a health-conscious

way

of life as well as corresponding genes, she could have given birth to a

child, the meaningful son of King Atala, just in time. Nonetheless, we

may wonder if the couple were willing to sacrifice him, probably their

only heir apparent, for the apparently planned provocation for slaying

the Niflungs. If they would not, any suitably aged son of King

Atala’s

concubine(s) could have been publicly introduced as Grimhild’s son.

As a heroic lay of the Elder Edda provides, Atli

let punish a

talkative

court-maid who alleged that Gudrun (= Grimhild) was sleeping

with Thiodrek

at Atli’s residence.

Regarding the pedigree of the Niflungs, as extracted

from

the

Svava and

Þiðreks

saga manuscripts, however, Grimhild’s youngest brother Gislher cannot

be the natural son of Queen Oda, spouse of the early died King Irung

(Mb 2; Mb 3: Alldrian), as

Ritter rightly stated.

10 Schlangenturm

and Irungs Wall

A former existence of a pallatium sive turris

(residence building or tower), ‘occupied by reptiles and other

creatures’, is provable to

high mediaeval Soest. Regarding also its homgarðr, William

J. Pfaff

reasonably agrues (op. cit. p. 175) by means of Henrik Bertelsen’s

source

text transcription and Ferdinand

Holthausen’s Studien zur Thidrekssaga:

A

document on

the authority of the

archbishop of Cologne

(c. 1178) relates that a ‘palace or tower’ next to the old church of

St. Peter had been full of reptiles, etc., and was then being used for

charitable purposes, probably a reference to the Hohe Spital southwest

of the church. There is no trace of the Nibelung name; perhaps

Högnagarðr

(B) and Niflungagardr

were added when Hom appeared (for bom) and the

obscurity had

led to confusion

with Holm- (II,310) for Norwegian scribes. There is, however,

ample

evidence that the Norwegian was not inventing these details; Holthausen

(464) suggests that the Edda may have taken the snake-pit motif from

northern Germany.

Challenging Ritter, Dietrich Hofmann (Christian-Albrechts-Universität

zu Kiel, German and Scandinavian studies) introductorily

attempted to

indicate the possibility that the localities of Soest, as specified by

the

manuscripts, had inspired a high mediaeval narrator for a

pseudo-historical relocation.

However, Hofmann then turned to

considering that this ‘reteller’ – more likely – might have had

only very little or no knowledge of the exact townscape in much former

times and, therefore, had to refer to contemporary structural

development for an impressing imagination of a former 6th-century

Franco-Saxon battle. Proceeding form this constellation it seems less

probable that the composer(s) of the Atlakviða,

one of the eldest Eddic lays of around A.D. 900, had taken its ormar

garðr motif from an apparently later erected episcopal site pallatium

sive turris which

was reported unkempt and, thereafter, noted on its restoration in 1178.

|

| |

|

Hofmann therefore argues onto the main

pretensions that, first, ‘the people

of

Westphalian Soest had taken outlandish legends for own historical

accounts’ and, second, ‘they

had little

or no knowledge of their own history’:

|

| |

|

However, the two

statements are still to

be modified a tad. On the one

hand, we may assume that some people in Soest and elsewhere knew better

about the true history of the city than the narrator of the Niflungs

history. Because of the conditions of ownership, not only the

archbishop of Cologne but also the Soest clergy ought to have been more

accurately informed about the ‘snake tower’ than anybody else. It is

rather to be expected that the belief in the historicity of the

Niflungs history

as a local history of Soest should have been widespread and strongly

rooted in the people’s mind. Otherwise the narrator would not have been

able to express himself so convincingly, as this version had apparently

spread even far beyond Soest. Some ‘intellectuals’, on the other hand,

could not argue to the contrary. The oral tradition was a great power

in the Middle Ages because it was thought to be historical and largely

supported. There was no other form of historical tradition

since centuries – even millenniums. The gradually developed

written tradition was not accessible to most of the people. Thus, they

had scarcely any means of examining and correcting the oral tradition

in the matter of historical facts. For this reason, the statements made

above on the conception of history might not only concern the citizens

of Soest in 12th/13th

century, but generally the perceptive opinion of history in the broad

population of the Middle Ages.

Ritter is, to a certain extent, still right by further necessary

modification of the two statements. One must also query how it could

have happened at all that the Soesters had a reception of a foreign

legend as their own story. The existence of remains of old walls and an

abandoned tower in which snakes were living is by no means sufficient

to

explain this. We can only proceed on the assumption that old

traditions were extant in Soest and esteemed there as historical before

the reception

of the Nibelungensage; for instance, stories about a mighty king in the

pre-Christian era, about heavy fighting on the western wall at the old

fortifications of the inner city, etc. Similarities in the course of

action

and the constellation of persons could have led to the fact that the

Nibelungensage, spread mainly by minstrels all over Germany and beyond,

was identified in Soest with stories of own tradition, presumably with

ballads. Of course, identical or similar names of acting persons could

significantly induce the identification and therewith the reception of

the Nibelungensage.

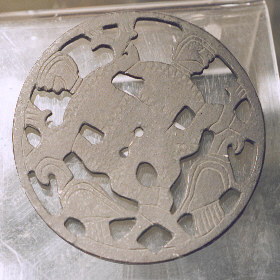

From this point of view it is by no means absurd, albeit purely

hypothetical, to argue with the name At(t)ano on

the disk fibula,

dated into the end of 6th century, as Ritter

has

done it, see pp. 207f.

In the Middle-Low-German period, the name would have developed to the

form *Attene

which might well have given an inducement to

an

identification with Attila. This, incidentally, is a literary

influenced form which shows that in Þidreks saga’s presentation a

portion of scholarship was involved who,

however,

obviously did not affect the believe in the correctness of the oral

tradition (…) Of course, as regards the Soest part of the

Niflungs history, comparably the same influenced constituents being

localized in other

places

and regions of Westphalia and the Rhineland, on which Ritter’s book

as

well as his previous treatises provide important awarenesses. It seems

clear

that the stories could also have gotten into the influential circle

of the Nibelungensage which, however, had no inherent correspondences

such as, potentially, a local tradition about the walled-up dead in the

Kallenhardt cave ‘Hohler Stein’ in the Sauerland, and which could have

been transferred to Attila.

|

| |

|

(Dietrich

Hofmann, “Attilas

Schlangenturm“ und der “Niflungengarten“ in Soest in:

Jahrbuch

des

Vereins für niederdeutsche Sprachforschung, 1981, vol. 104, pgs

31–46. Translation from pgs 44–45.)

|

|

|

A plan with

contour

lines of

the old centre by municipal registry of

1830. Hofmann refers to a corresponding reconstruction drawing by F. W.

Landwehr, see p. 40. See Ritter 1981:193 who does not estimate the

large

building at the episcopal place of residence ‘Pfalz’ as Gunnar’s

‘snake tower’, see also pgs 199–203.

According to the manuscripts Hǫgni had left in Soest the obvious most

impressive actions, as these are his bursting through the western wall,

fighting ferociously against Irung and then Þiðrek, and,

finally, generating a son for revenge on the patron, ‘father’ or ‘Ata’

of Soest.

Since the place of Hǫgni’s ancestors has

been suggested at Troyes, we should think more complexly

about the reasons why Archbishop Bruno of Cologne had the mortal

remains of St. Patroclus transferred from Frankish Troyes

via Cologne to Soest as its new Christian

patron. This ‘installation’ extended from 962 to 964. |

|

| |

|

Dr Heinrich ten

Doornkaat

Koolman, a former Mayor of Soest, wrote on the obvious relicts of an

elder or, relatively, the eldest known wall:

|

| |

Wie

in der Zeitschrift des Soester

Geschichtsvereins

Nr. 14 Seite 22 ff. berichtet wird, kamen 1884 bei den

Ausschachtungsarbeiten für ein neues Pfarrhaus an der Ecke des

Petrikirchhofes und der Hospitalgasse alte Mauerreste zum Vorschein.

Gücklicherweise hat man den Fund sorgfältig aufgemessen, und

eine von dem Baumeister Lange am 16.7.84 angefertigte

maßstäbliche Zeichnung ist in dem Heft 14 S. 24/25

wiedergegeben.

Danach hat eine von Norden nach Süden

verlaufende, 1,80 m in die Tiefe reichende Mauer den Petrikirchhof von

dem zum Hohen Hospital gehörenden Gebiet geschieden. In einer

anschließenden von Osten nach Westen verlaufenden, aus

großen behauenden Quadern aufgeführten Mauer von reichlich 1

m Dicke befanden sich unter der Erdoberfläche zwei etwa 2,20 m

hohe und etwa 1,80 m weite rundbogige Torbogen. Weiter befand sich

ein Haufen Bauschutt untermischt mit Resten verkohlten Gebälks.

In dem Bericht ist weiter vermerkt, diese Mauer

müsse zum Hohen Hospital in Beziehung

gestanden haben,

wenn sie auch keineswegs einen Teil des Gebäudes gebildet habe.

Dafür, daß dies nicht der Fall gewesen, spreche die

völlige

Verschiedenheit des Mauerwerks.

Dies Alles deutet auf eine ältere

Burganlage hin, die vor der Errichtung der merowingischen Pfalz

bestanden hat.

(Heinrich ten Doornkaat Koolman, Soest

die Stätte des Nibelungenunterganges? Rochol, Soest

1937, see pgs

10–11.)

Drawings on the right are taken from the article quoted by

H. ten Doornkaat Koolman.

|

|

|

[Transl.:

As reported in the magazine of the Soester

Geschichtsverein, No. 14, page 22f., 1884, old fragments of the

wall came to light during the

excavation work for a new vicarage at the corner of the Petrikirchhof

and the Hospitalgasse. Fortunately, this find was carefully measured,

and a scaled plan drawn on 16 July 1884 by Mr. Lange, master builder,

is reproduced in issue 14, pgs 24–25.

According to that a wall extending from north

to south, reaching a depth of 1.80 m, separated the Petrikirchhof from

the area belonging to the Hohen Hospital. In an adjoining wall

extending from east to west, not less than 1 m in thickness and

consisting of large chiselled cuboids, two bows of arched gates, c.

2.20 m high and c. 1.80 m wide, were found under the ground. There

was also a heap of building rubble mixed with the remains of charred

timberwork.

The report also notes that this wall must

have been related to the Hohen Hospital, even though it was by no means

a part of the building, as this might be supported well enough by the

complete difference of the stonework.

All this points to an older fortification

which existed before the erection of the Merovingian Palatinate.]

|

| |

|

Ritter supplements

on this article an obvious later excavation, ‘commissioned by the Historischer

Verein

of Soest in 1951/1952’ as he writes, whose experts had uncovered a wall

(c. 2.5 m

thick) even under the foundation level of the Pfalz. Ritter

summarizes that

the archaeologists of this excavation found under this wall strata with

remains of

carbonized

material and scattershot skeleton fragments and, thereupon, drew the

assumptive conclusion that on this location ‘heavy combats had taken

place in the

early Middle Ages’. Ritter quotes as follows from its report (1981:198)

by

Hubertus Schwarz: Soest in seinen

Denkmälern, Soest 1955, p. 134:

|

| |

Unter den Fundamenten (…)

fanden sich unter einer gleichmäßig waagrechten,

tiefschwarzen Holzkohlenschicht von 2 cm Dicke in 1,30–2,30 m Tiefe

(…)

»in

ihrer ganzen Stärke, besonders aber nach unten

hin, wahllos zerstreut, menschliche Knochenreste, die zumeist, auch die

Schädel, zertrümmert und zum Teil auch angebrannt waren. In

2,20 m Tiefe konnte noch eine 1–2 cm starke, scharf abgesetzte

Holzkohlenschicht festgestellt werden, unter welcher unmittelbar wieder

menschliche Schädel- und Knochenfragmente lagen. Da diese

Schichten nur an der Südseite der sogenannten ›Wittekindsmauer‹

auftreten und noch weiter in die Tiefe gehen, liegen sie im Innern im

Keller eines alten Bauwerks, das als Vorläufer des ›Hohen

Hospitals‹ (= Veste) angesehen werden

muß.«

(…)

»Das ganze

Auftreten dieser Schichten mit ihrem auffallenden Inhalt in den Kellern

eines Bauwerks, dessen Mauern 8 Fuß =

rund 2,50 m

breit waren,

läßt an dieser hervorragenden Stelle des alten Burgbezirks

schwere Kampfhandlungen im frühen Mittelalter

vermuten.«

|

| |

|

[Transl.:

Downward the foundations (…) under a deep

black

charcoal stratum of 2 cm thickness, running undisturbed horizontally at

a depth of 1.30 to 2.30 m were found (…)

«in

all of its

dimension, increasingly downward, randomly

scattered human bone remains and skulls which were smashed and partly

burned. Further, then at a depth of 2.20 m, a sharply stepped 1 to 2 cm

thick charcoal stratum was localized again with fragments of human

skulls

and bones. Since these strata were found only under the south side of

the so-called ‹Wittekindsmauer› and lie farther in the depths, they

meet the inner domain of the basement of an old structure which must be

regarded as the previous building of the ‹ fortification =)›

‹Hohen Hospital›.»

(…) «The whole appearance of these strata, with their

striking contents in the basement of a building, whose walls were

8 feet or 2.50 m wide, admits to presume heavy fighting in the

early Middle Ages at this eminent place related to the old

fortification.»]

|

|

11 Sigfrid’s Niflunga

Hoard

The hoard, most probably a cave, should meet these

requirements:

| 1. |

This location must be easily

reachable from

starting point,

King Atala’s residence, for a twelve years old boy and an elder man on

horses, but without an escort or entourage. |

| 2. |

The position and inlet of the cave must not be

found

with ease in the

natural environment. |

| 3. |

The cave must contain mortal remains of a man

covered

with earth or

other natural material after passing one and a half millennium. |

| 4. |

The position of the dead body must not indicate a

burial. |

| 5. |

The dead may not be as died young. His date of

death

must be verifiable

to pre-christian time of that territory. |

| 6. |

Considering the secret trip to the cave, the

remaining

personal accessories

of the dead must be ascribable to a ruler of 6th

century. |

A cave which meets these conditions was found in a rocky

hill at

Kallenhardt, Warstein,

in 1926:

In the tunnel of that Hohler Stein (‘Hollow

Rock’),

mortal remains

of a man were found in an undisrupted stratum. The procedure of a

burial appeared impossible for the position and environment of the

remains. The age of the dead man was determined

to

nearly 50. The jewellery found at his skeleton, which are a rune

fibula, an arm

ring,

a finger ring and knobs, are preserved today at North-Rhine-Westphalian

museums of Lippstadt and Münster.

Prof

Stieren and Dr Julius Andree directed this

exploration.

On the next official excursion (made in 1933) relicts of

a forgery of the Thirty Years' War were found at the western inlet of

the cave that still has an

unspecified

number of tunnels. As Ritter notes in his book on the Nibelungs'

history,